In late 2013, archaeologists excavating in advance of a driveway construction project near Gyeongju, a town in southeastern Korea that was the ancient capital of the Silla Kingdom, unearthed human skeletal remains. Found in a mokgwakmyo, a traditional wooden coffin, in a marshy area, the skeleton was complete and relatively well-preserved, albeit fragmented in places. Grave goods, including pottery and a wooden comb, were found inside the coffin that identify it as a Silla-era burial.

In late 2013, archaeologists excavating in advance of a driveway construction project near Gyeongju, a town in southeastern Korea that was the ancient capital of the Silla Kingdom, unearthed human skeletal remains. Found in a mokgwakmyo, a traditional wooden coffin, in a marshy area, the skeleton was complete and relatively well-preserved, albeit fragmented in places. Grave goods, including pottery and a wooden comb, were found inside the coffin that identify it as a Silla-era burial.

The Silla Kingdom started as a small city-state in 57 B.C. and ruled an increasingly large part of the Korean Peninsula until 935 A.D. Its thousand-year duration is one of the longest in the historical record, and two of its ruling dynasties — the Parks and the Kims — transcended the kingdom to become the most common family names in Korea today.

Despite the Silla Kingdom’s long life and enormous influence on the history and modern culture of Korea, researchers have had few opportunities to study Silla bones at all, and never with multiple analytical technologies. Intact human remains from the Silla period are rare because Korea’s acidic soil and the cycles of hot/wet, cold/dry weather accelerate the decomposition of soft tissue and bone alike. A 4th-6th century grave discovered in 2009 contained unprecedented complete sets of human and horse armor, for example, but not a single human remain. The wooden coffin survived, as did a box with assorted grave goods. The bones had disintegrated. The discovery of a complete skeleton in 2013 gave scientists the chance to carry out anthropological analysis, extract mitochondrial DNA, run stable isotope tests and craniofacial analyses that led to a full facial reconstruction.

Despite the Silla Kingdom’s long life and enormous influence on the history and modern culture of Korea, researchers have had few opportunities to study Silla bones at all, and never with multiple analytical technologies. Intact human remains from the Silla period are rare because Korea’s acidic soil and the cycles of hot/wet, cold/dry weather accelerate the decomposition of soft tissue and bone alike. A 4th-6th century grave discovered in 2009 contained unprecedented complete sets of human and horse armor, for example, but not a single human remain. The wooden coffin survived, as did a box with assorted grave goods. The bones had disintegrated. The discovery of a complete skeleton in 2013 gave scientists the chance to carry out anthropological analysis, extract mitochondrial DNA, run stable isotope tests and craniofacial analyses that led to a full facial reconstruction.

The person deceased was a woman between 35 and 39 years of age at time of death. The length of the femur indicated she was around 155 cm (five feet) tall. The mitrochondrial DNA results placed her haplogroup F1b1a, a haplogroup typical of East Asia but not the dominant group in living Koreans today. Stable isotope analysis found that her diet consisted mainly of foods in the C3 category (wheat, rice and potatoes) and was likely vegetarian.

The person deceased was a woman between 35 and 39 years of age at time of death. The length of the femur indicated she was around 155 cm (five feet) tall. The mitrochondrial DNA results placed her haplogroup F1b1a, a haplogroup typical of East Asia but not the dominant group in living Koreans today. Stable isotope analysis found that her diet consisted mainly of foods in the C3 category (wheat, rice and potatoes) and was likely vegetarian.

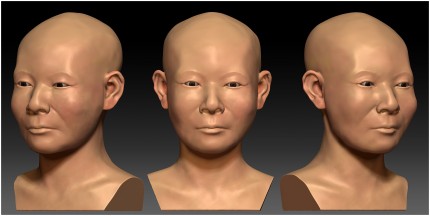

Her skull was found broken in dozens of pieces. In order to help determine her gender and to create a facial reconstruction, archaeologists cleaned the fragments and dried them. Each piece was scanned and imported into 3D modelling software to figure out how the pieces fit together. Once the model was complete, the team then puzzled together the actual skull from the fragments.

Her skull was found broken in dozens of pieces. In order to help determine her gender and to create a facial reconstruction, archaeologists cleaned the fragments and dried them. Each piece was scanned and imported into 3D modelling software to figure out how the pieces fit together. Once the model was complete, the team then puzzled together the actual skull from the fragments.

Her skull was unusually long and narrow. This kind of head shape often seen in cases of intentional cranial deformation. It appears to be natural in her case. Intentionally deformed crania are flatter in the front and the bones of the side grow to compensate from the pressure of the deforming agent (usually a piece wood or tight bindings applied to infants when their skulls are still soft).

In the craniometric analysis, the major cranial indices were compared with the corresponding data derived from the subjects of modern Korean adults. The results showed that the skull has longer, narrower and lower cranium with a narrower facial bone and orbits than those from the modern Korean adults groups. The nasal aperture demonstrated an average width in the nasal index. In terms of appearance, it was assumed that the individual had horizontally long & vertically short head with inclined forehead from lateral view and narrower face from frontal view.

This dolichocephalic or long-headedness trait is rare in the population of Korea today. Koreans are more often brachycephalic, defined as the width of their skull being at least 80% of the length.

Here is the complete craniofacial reconstruction:

You can read the full study published in the journal PLOS ONE here.