A large Roman-era mosaic floor depicting chariot racing has been revealed in full after a year of excavations in the village of Akaki outside Nicosia, Cyprus. Excavations on the site began in 2014 when the remains of a large cistern 10 x 14 meters (33 x 46 feet) in dimension were discovered. In the summer of 2015, a section of a mosaic was unearthed on the south side of the cistern. Its large size, exceptional quality and very rare depiction of a chariot race distinguished it as one of the most important archaeological discoveries in Cyprus.

A large Roman-era mosaic floor depicting chariot racing has been revealed in full after a year of excavations in the village of Akaki outside Nicosia, Cyprus. Excavations on the site began in 2014 when the remains of a large cistern 10 x 14 meters (33 x 46 feet) in dimension were discovered. In the summer of 2015, a section of a mosaic was unearthed on the south side of the cistern. Its large size, exceptional quality and very rare depiction of a chariot race distinguished it as one of the most important archaeological discoveries in Cyprus.

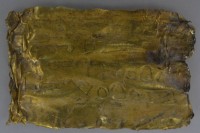

This year’s dig has exposed almost all of the mosaic. It is 11 meters long and four meters wide (36 by 13 feet) and was likely part of the floor of a large villa. It dates to the first half of the 4th century. Much of it is in a good state of preservation. The ornately decorated scene shows four quadrigae (chariots drawn by a team of four horses as in Ben Hur), possibly representing the four factions of professional racers in the Roman world — the Reds, Whites, Greens, and Blues — competing in a race at a circus or hippodrome. The chariots race around the spina, the median running down the center of the track. The charioteers are all standing and each quadriga is labeled with two inscriptions that are probably the names of the charioteer and the lead horse.

This year’s dig has exposed almost all of the mosaic. It is 11 meters long and four meters wide (36 by 13 feet) and was likely part of the floor of a large villa. It dates to the first half of the 4th century. Much of it is in a good state of preservation. The ornately decorated scene shows four quadrigae (chariots drawn by a team of four horses as in Ben Hur), possibly representing the four factions of professional racers in the Roman world — the Reds, Whites, Greens, and Blues — competing in a race at a circus or hippodrome. The chariots race around the spina, the median running down the center of the track. The charioteers are all standing and each quadriga is labeled with two inscriptions that are probably the names of the charioteer and the lead horse.

At the eastern end of the spina is the meta, the turning point where the greatest concentration of accidents, often fatal to rider and horses, occurred as the driver attempted to maneuver four galloping horses and one two-wheeled vehicle tightly around the curve. The meta is shown as a circular platform with three cones, each topped with an egg. The spina is decorated with an aedicule (a small temple) on one end and three columns, each topped with a dolphin with water pouring out of its mouth, in the middle. Standing between the chariots on the track are two men, one holding a whip, the other a vessel of water. There is also a figure on horseback.

At the eastern end of the spina is the meta, the turning point where the greatest concentration of accidents, often fatal to rider and horses, occurred as the driver attempted to maneuver four galloping horses and one two-wheeled vehicle tightly around the curve. The meta is shown as a circular platform with three cones, each topped with an egg. The spina is decorated with an aedicule (a small temple) on one end and three columns, each topped with a dolphin with water pouring out of its mouth, in the middle. Standing between the chariots on the track are two men, one holding a whip, the other a vessel of water. There is also a figure on horseback.

The scene is encased in borders of intricate geometric designs. At the western end of the floor is another mosaic, nine medallions arranged in a circle, each holding the bust of a female figure. While this section has yet to be fully cleaned, already it’s clear that the nine figures are the muses, each identifiable from the symbols they hold.

The scene is encased in borders of intricate geometric designs. At the western end of the floor is another mosaic, nine medallions arranged in a circle, each holding the bust of a female figure. While this section has yet to be fully cleaned, already it’s clear that the nine figures are the muses, each identifiable from the symbols they hold.

Racing scenes like this one are extremely rare in the eastern provinces of the Roman empire, and even in the west they can be counted in single digits. Only two have been discovered in Greece and a total of seven have been found elsewhere in the empire (North Africa, France and Spain). The find is particularly exciting because it is the only such mosaic ever found in Cyprus, and it was discovered inland, about 20 miles west of Nicosia. The vast majority of Roman archaeological material has been found along the coast of the island.

Racing scenes like this one are extremely rare in the eastern provinces of the Roman empire, and even in the west they can be counted in single digits. Only two have been discovered in Greece and a total of seven have been found elsewhere in the empire (North Africa, France and Spain). The find is particularly exciting because it is the only such mosaic ever found in Cyprus, and it was discovered inland, about 20 miles west of Nicosia. The vast majority of Roman archaeological material has been found along the coast of the island.

Speaking to journalists, Director of the Department of Antiquities Marina Ieronymidou said: “It is an extremely important finding, because of the technique and because of the theme. It is unique in Cyprus since the presence of this mosaic floor in a remote inland area provides important new information on that period in Cyprus and adds to our knowledge of the use of mosaic floors on the island.”

Excavations will continue next May when archaeologists hope to unearth more of the mosaic floor and the villa. Until then, the floor will be covered with protective temporary structures.