An Egyptian epitaph from the 3rd century A.D. has been recently translated revealing a unique combination of descriptors. The epitaph is part of a collection of Greek and Coptic artifacts in the University of Utah’s J. Willard Marriott Library. The collection was donated to the library in 1989 after the death of the collector, Doctor Aziz Suryal Atiya, an eminent Coptic historian who taught history at the University of Utah and founded the university’s Middle East Center in 1959. The Aziz S. Atiya Middle East Library, an internationally renown center for research in Middle Eastern history with the fifth largest collection in the United States, has hundreds of thousands of books, manuscripts and rare artifacts.

An Egyptian epitaph from the 3rd century A.D. has been recently translated revealing a unique combination of descriptors. The epitaph is part of a collection of Greek and Coptic artifacts in the University of Utah’s J. Willard Marriott Library. The collection was donated to the library in 1989 after the death of the collector, Doctor Aziz Suryal Atiya, an eminent Coptic historian who taught history at the University of Utah and founded the university’s Middle East Center in 1959. The Aziz S. Atiya Middle East Library, an internationally renown center for research in Middle Eastern history with the fifth largest collection in the United States, has hundreds of thousands of books, manuscripts and rare artifacts.

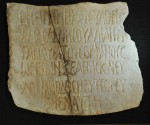

The inventory note for the epitaph described it as a “Coptic inscription, dating from the dawn of the use of the Greek alphabet, not earlier than the second century, but not later than the third.” The small limestone slab, seemingly unremarkable, was left untranslated for more than 25 years until it caught the eye of Brigham Young University adjunct professor of ancient scripture Lincoln H. Blumell. He realized the description was wrong, that the inscription was in ancient Greek, not in Coptic using Greek letters.

The inscription reads:

In peace and blessing Ama Helene, a Jew, who loves the orphans, [died]. For about 60 years her path was one of mercy and blessing; on it she prospered.

It’s the combination of the honorific “Ama,” a title used to describe Christian women, mainly nuns, in late ancient Egypt, with her Jewish identification that is unprecedented.

“I’ve looked at hundreds of ancient Jewish epitaphs,” Blumell said, “and there is nothing quite like this. This is a beautiful remembrance and tribute to this woman.” […]

Considering the unique use of dual-faith identifiers and the timeframe alone, the epitaph is unique with no known parallels.

Additionally, Blumell notes there is even more to the inscription. Scholars have noted from other inscriptions that Egyptian women during this timeframe had a life expectancy of 25 years. To live 60 years, as noted in the inscription, was incredible. Also, during a time when any sort of social programs were unavailable to orphans, taking care of them was seen as a very noble pursuit. Serving the widows and orphans is a common call to action in the New Testament.

I had doubts about that life expectancy statistic. I thought it might be a misinterpretation of average life expectancy, an average which is extremely low in places and times when infant and child mortality was high. The average age of death skews far younger because so many children died young. Once people managed to survive to adulthood their real life expectancy was significantly higher. I was wrong. According to ancient census data from Egypt in the first three centuries A.D., fully 61% of women were dead by the age of 30. Men had it only slightly better with 59% dying before they hit their 30s. Helene was one of fewer than 6% of Egyptian women from this period who lived to see 60.

I had doubts about that life expectancy statistic. I thought it might be a misinterpretation of average life expectancy, an average which is extremely low in places and times when infant and child mortality was high. The average age of death skews far younger because so many children died young. Once people managed to survive to adulthood their real life expectancy was significantly higher. I was wrong. According to ancient census data from Egypt in the first three centuries A.D., fully 61% of women were dead by the age of 30. Men had it only slightly better with 59% dying before they hit their 30s. Helene was one of fewer than 6% of Egyptian women from this period who lived to see 60.

Blumell has published his findings in the forthcoming issue of the Journal for the Study of Judaism.