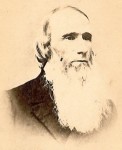

John Scott Harrison, born October 4th, 1804, bears the unique distinction of having been both the child and father of US Presidents. His father William Henry Harrison was the ninth President and holds the record for the shortest tenure, having died of pneumonia on the 32nd day of his presidency. John Scott’s son Benjamin Harrison was the 23rd President, serving one full term from 1889 to 1893. The Honorable John Scott Harrison was a Congressman from Ohio, a gentleman farmer, a family man and a highly respected member of his community, but if he is remembered at all today, it is for what happened to him after his death, a true tale of horror that caused a nation-wide sensation.

John Scott Harrison, born October 4th, 1804, bears the unique distinction of having been both the child and father of US Presidents. His father William Henry Harrison was the ninth President and holds the record for the shortest tenure, having died of pneumonia on the 32nd day of his presidency. John Scott’s son Benjamin Harrison was the 23rd President, serving one full term from 1889 to 1893. The Honorable John Scott Harrison was a Congressman from Ohio, a gentleman farmer, a family man and a highly respected member of his community, but if he is remembered at all today, it is for what happened to him after his death, a true tale of horror that caused a nation-wide sensation.

After a peaceful death in his bed at Point Farm the night of May 25th, 1878, John Scott Harrison was buried in the family plot overlooking the Ohio River Valley in Congress Green Cemetery, North Bend, Ohio. The funeral took place on May 29th. As family and friends walked to the grave for the burial service, they were dismayed to see that the still-fresh grave of their kinsman Augustus Devin had been disturbed. John Scott’s daughter Sarah was married to Augustus’ uncle Thomas Jefferson Devin, and the families were very close. In fact, John Scott had visited Augustus two weeks before the 23-year-old died of tuberculosis, only to unexpectedly follow him to the grave just a week later. At first the funeral party thought wild hogs might be responsible for the churned-up soil at Augustus Devin’s grave, but upon closer inspection they found the young man’s body was gone, stolen by body-snatchers, the reviled resurrection men who made their living by trafficking the dead.

After a peaceful death in his bed at Point Farm the night of May 25th, 1878, John Scott Harrison was buried in the family plot overlooking the Ohio River Valley in Congress Green Cemetery, North Bend, Ohio. The funeral took place on May 29th. As family and friends walked to the grave for the burial service, they were dismayed to see that the still-fresh grave of their kinsman Augustus Devin had been disturbed. John Scott’s daughter Sarah was married to Augustus’ uncle Thomas Jefferson Devin, and the families were very close. In fact, John Scott had visited Augustus two weeks before the 23-year-old died of tuberculosis, only to unexpectedly follow him to the grave just a week later. At first the funeral party thought wild hogs might be responsible for the churned-up soil at Augustus Devin’s grave, but upon closer inspection they found the young man’s body was gone, stolen by body-snatchers, the reviled resurrection men who made their living by trafficking the dead.

Horrified by this discovery and concerned that their father might suffer a similar indignity, Benjamin and his brothers John and Carter took additional measures to secure his final resting place. The grave was already brick vaulted with a thick stone bottom. They placed three large, heavy stone slabs eight inches thick on top of the metal casket — the largest at the head and the two smaller ones at the foot — and poured cement over them to create a solid block weighing nearly a ton. The grave was kept open for several hours until the cement dried. It was then filled and the family paid a watchman a dollar a night to guard the grave for 30 nights. Having seen his father safely to his eternal repose, Benjamin Harrison, a distinguished attorney and already a prominent figure in the Republican party, returned to his home in Indianapolis to prepare for a speech he was giving at the Republican State Convention on June 5th.

Horrified by this discovery and concerned that their father might suffer a similar indignity, Benjamin and his brothers John and Carter took additional measures to secure his final resting place. The grave was already brick vaulted with a thick stone bottom. They placed three large, heavy stone slabs eight inches thick on top of the metal casket — the largest at the head and the two smaller ones at the foot — and poured cement over them to create a solid block weighing nearly a ton. The grave was kept open for several hours until the cement dried. It was then filled and the family paid a watchman a dollar a night to guard the grave for 30 nights. Having seen his father safely to his eternal repose, Benjamin Harrison, a distinguished attorney and already a prominent figure in the Republican party, returned to his home in Indianapolis to prepare for a speech he was giving at the Republican State Convention on June 5th.

![Ad for Medical College of Ohio in Williams' Cincinnati Directory of 1856. "The Dissecting Rooms will be opened on the first of October, under the care of the Demonstrator of Anatomy, and students may rely on a full supply of materiel [ie, dead bodies] throughout the session."](http://www.thehistoryblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Ad-for-Medical-College-of-Ohio-in-Williams-Cincinnati-Directory-of-1856-90x150.jpg) Benjamin’s youngest brother John Harrison went to Cincinnati with his nephew George Eaton to find and reclaim young Augustus’ body before the grieving mother had to be told it was gone. There was little question in their mind where the body had wound up. It was almost certainly sold to a local medical school, the primary receivers of stolen human flesh. While the Anatomy Act of 1832 had ended the illicit cadaver trade in the UK by supplying anatomy schools with bodies of unclaimed indigents, the federal system in the United States left that kind of legislation to individual states, and the notion of handing over the bodies of the poor for dissection offended American religious and moral sensibilities so much that few states made such provisions. This combined with the explosion of new medical schools in the mid-19th century (in 1800 there were 4 medical schools in the whole country; by 1876 there were 73; by the end of the century there were dozens more) to create a massive demand for anatomical “materiel” that the resurrection men were only too glad to fill.

Benjamin’s youngest brother John Harrison went to Cincinnati with his nephew George Eaton to find and reclaim young Augustus’ body before the grieving mother had to be told it was gone. There was little question in their mind where the body had wound up. It was almost certainly sold to a local medical school, the primary receivers of stolen human flesh. While the Anatomy Act of 1832 had ended the illicit cadaver trade in the UK by supplying anatomy schools with bodies of unclaimed indigents, the federal system in the United States left that kind of legislation to individual states, and the notion of handing over the bodies of the poor for dissection offended American religious and moral sensibilities so much that few states made such provisions. This combined with the explosion of new medical schools in the mid-19th century (in 1800 there were 4 medical schools in the whole country; by 1876 there were 73; by the end of the century there were dozens more) to create a massive demand for anatomical “materiel” that the resurrection men were only too glad to fill.

An item in the Cincinnati Enquirer on the morning of May 30th gave Harrison and Eaton a valuable clue to the possible whereabouts of the missing body:

A Mystery. About three o’clock this morning, a sensation was created on Vine street by a buggy being driven into the alley north of the Grand Opera house. It proceeded about half way through to Race street, when something white was taken out and disappeared. Several men started in to see what was going on, when the buggy drove out to Race street and left rapidly. The general impression was that a “stiff” was being smuggled into the Ohio Medical College.

This small blurb and the outrage to a well-connected family with legal clout was sufficient for John Harrison and George Eaton to secure a search warrant that very day for the Medical College of Ohio. Armed with the warrant, Harrison and Eaton, accompanied by former Cincinnati Chief of Police Colonel Thomas E. Snelbaker, Constable Lacey and Deputy Constable Tallen of the Cincinnati police, went to the college and insisted on searching the premises. They were accompanied by the very apprehensive janitor, A.Q. Marshall, who protested that the officers of the college should be present before they turned the place upside down.

The party proceeded to search every room on all five floors of the building, from cellar to garret. In the cellar they found a chute that opened onto the alley between Vine and Race Streets where the buggy had been seen dumping a suspicious white bundle at 3:00 o’clock that morning. This was how the resurrectionists surreptitiously delivered cadavers to the medical school. No need for daylight transactions that might raise awkward questions; no need for the faculty to interact with the grave-robbers in the presence of the evidence of their crimes. Another chute, this one running vertically from the cellar to the top of the building, was connected to it. The search party looked into both chutes, illuminating the darkness with their lamps, but saw nothing.

The party proceeded to search every room on all five floors of the building, from cellar to garret. In the cellar they found a chute that opened onto the alley between Vine and Race Streets where the buggy had been seen dumping a suspicious white bundle at 3:00 o’clock that morning. This was how the resurrectionists surreptitiously delivered cadavers to the medical school. No need for daylight transactions that might raise awkward questions; no need for the faculty to interact with the grave-robbers in the presence of the evidence of their crimes. Another chute, this one running vertically from the cellar to the top of the building, was connected to it. The search party looked into both chutes, illuminating the darkness with their lamps, but saw nothing.

Most of the rooms upstairs were empty too, though they searched every lumber pile, box and closet. Then they came upon a dissection room. A student was using it for its intended purposes, cutting into a partial body — the head and chest of a black woman — merrily slicing away at the already putrefying flesh. Walking briskly past this macabre scene, they found a box of assorted limbs cut from cadavers and kept for later use. Mixed in with the arms and legs was the intact body of a six-month-old baby.

Most of the rooms upstairs were empty too, though they searched every lumber pile, box and closet. Then they came upon a dissection room. A student was using it for its intended purposes, cutting into a partial body — the head and chest of a black woman — merrily slicing away at the already putrefying flesh. Walking briskly past this macabre scene, they found a box of assorted limbs cut from cadavers and kept for later use. Mixed in with the arms and legs was the intact body of a six-month-old baby.

Disgusted and disturbed, they moved on to the top floor of the building. By this time, the police had allowed the janitor to leave, ostensibly to notify the school officers of the search, but Colonel Snelbaker was smart enough to have him followed. Instead of running off to alert the faculty, Mr. Marshall went upstairs to a room at the southeast corner of the building. He realized he was being shadowed so he turned around before entering, but it was too late. The cops now knew there was something worth hiding in that room.

John Harrison, George Eaton and the three police officers entered the suspicious room, finding boxes, a few bones, papers and assorted junk. In a corner of the room near a window was a windlass. A rope ran from it into a square hole in the floor, presumably reaching the bottom of the long chute in the cellar. This is how the bodies were moved from the cellar to the dissection rooms: they were tied to a rope and lifted by the windlass at the top of chute. Snelbaker saw that the rope was taut as if something heavy was tied to it. He turned the windlass and slowly the body of a man emerged from the hole, the rope tied around his neck and under one arm. He was naked except for a tattered shirt and a cloth covering his head.

John Harrison, George Eaton and the three police officers entered the suspicious room, finding boxes, a few bones, papers and assorted junk. In a corner of the room near a window was a windlass. A rope ran from it into a square hole in the floor, presumably reaching the bottom of the long chute in the cellar. This is how the bodies were moved from the cellar to the dissection rooms: they were tied to a rope and lifted by the windlass at the top of chute. Snelbaker saw that the rope was taut as if something heavy was tied to it. He turned the windlass and slowly the body of a man emerged from the hole, the rope tied around his neck and under one arm. He was naked except for a tattered shirt and a cloth covering his head.

John realized before the face was revealed that it could not be his cousin Augustus. The body was that of an old man in comparatively good health, not of a youth emaciated by the ravages of consumption. He was about to walk away when Snelbaker urged him to check, just in case. They pulled the body into the room and laid it on the floor. Blood trickled from a loosely stitched neck incision, forced out by the pressure of the rope. Slowly and somberly, Snelbaker loosened the rope around his neck so the cloth covering his face could be lifted.

John realized before the face was revealed that it could not be his cousin Augustus. The body was that of an old man in comparatively good health, not of a youth emaciated by the ravages of consumption. He was about to walk away when Snelbaker urged him to check, just in case. They pulled the body into the room and laid it on the floor. Blood trickled from a loosely stitched neck incision, forced out by the pressure of the rope. Slowly and somberly, Snelbaker loosened the rope around his neck so the cloth covering his face could be lifted.

Harrison had been right; it wasn’t the body of Augustus Devin. Under the cloth was the face of an elderly man, discolored and bruised from the rope and careless treatment at the hands of the resurrection men. He had short white hair and a snow-white beard cropped an inch below his chin. John Harrison staggered, suddenly weak at the knees. “It’s father,” he rasped, and collapsed to the floor. The body of the Honorable John Scott Harrison, buried in a cement-reinforced bricked vault less than 24 hours earlier, had been stolen from the grave, stripped of his clothing, shorn of his distinctive waist-length beard, and dangled from a rope in the cadaver chute of a medical school.