The National Trust has

acquired a very fine early 17th century miniature by Isaac Oliver for £2.1 million ($2,760,000), a new record for a British miniature. The miniature is widely acknowledged as one of the greatest British examples of the art form. It has been on display at the

Powis Castle in Powys, Wales, which was bequeathed to the National Trust by 4th earl of Powis in 1952. The anonymous seller, believed to be in the family of the Earls of Powis, sold the miniature at a discount — it was valued at £5.2 million ($6,830,000) — in exchange for tax concessions. Even so, the National Trust had to raise funds to buy the piece and save it for the nation before it went up for public sale. The Art Fund contributed £300,000 ($394,000), the National Heritage Memorial Fund £1.5 million ($1,970,000) and the National Trust pulled together the rest from various sources.

The subject of the miniature is Edward Herbert, 1st Baron Herbert of Cherbury (1583-1648), a soldier, diplomat, statesman, poet, playwright and philosopher. His first cousin was Sir William Herbert, 1st Lord Powis. Scholars believe the miniature has been in the Powis family almost since it was first painted.

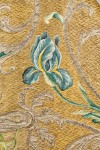

The cabinet miniature measures nine by seven inches and presents him as a chivalric hero of medieval romance, reclining in a verdant glade by a babbling brook. Lying recumbent with his head propped up on one hand, Herbert strikes the pose of the melancholic, symbolic of deep thought and contemplation. This isn’t just the image of a philosophically minded young man, however. Herbert is the Melancholy Knight here, shown in repose after dueling in a joust. His shield, decorated with a winged heart rising from the flames and the inscription “Magia Sympathiae,” (“sympathetic magic,” an element in Herbert’s metaphysical treatise De Veritate on the pursuit of truth) covers his arm, while in the background his elegant suit of armour is perched between two trees and his page holds a helmet so extravagantly beplumed that the red feathers obscure the page’s face entirely. To the right of the page, Herbert’s armoured white destrier paws the ground spiritedly. In the far distance, painted in blue, is a city on a river.

Edward Herbert was a dashing figure of the era, famed for his bravery, intellect and success with the ladies. The miniature was painted around 1610-1614, a time when Herbert had distinguished himself in highly chivalric fashion while volunteering under Philip William, Prince of Orange, in the Low Countries. From 1609 through 1614, the Dutch Republic was involved in the War of the Jülich Succession over who would control the United Duchies of Jülich-Cleves-Berg. Holy Roman Emperor Rudolph II claimed the duchy, as did Wolfgang William, Duke of Palatinate-Neuburg, John Sigismund, Elector of Brandenburg, and the Prince of Orange representing the interests of the Dutch Republic.

In 1610, the emperor’s troops occupied the fortified citadel of Jülich and the armies of the Republic, Palatinate-Newburg and Brandenburg came together to besiege it. Herbert stepped forward to propose a classic solution to the conflict: he offered to fight the Holy Roman Emperor’s chosen champion in single combat. The victorious champion would win the duchy for his lord. Rudolph II declined. The siege lasted 35 days before the Imperial troops surrendered and withdrew and Rudolph renounced his claim to the duchy.

Born in France the son of a Huguenot goldsmith named Pierre Olivier who anglicized his last name when he fled persecution in Rouen and moved to England, Isaac Oliver was 27 and already an experienced painter when he became a pupil in the workshop of painter Nicholas Hilliard who was a popular miniature portraitist of the Tudor court.

Hilliard was limited in his skills, however, sticking largely to relatively flat head-and-shoulders portraits. When Oliver began painting miniatures under Hilliard in 1587 he was quickly recognized as a great talent and an innovator of the genre, which was less than 70 years old at that time. His portraits covered more of the body, used more and brighter colors, added chiaroscuro shadow elements that gave the features more depth and dimension. Oliver introduced the naturalism of Renaissance Italian and Flemish painters to British miniatures, and his works were widely collected by the young and fashionable.

There is an extremely juicy backstory to the miniature, one that appropriately enough for Herbert involves a married woman, a pissed off husband, attempted murder and attempted duels. The tale is recounted by Edward Herbert himself in his scandalous autobiography which was only published a century after his death by Horace Walpole, publisher, author and son of the first prime minister of Britain Robert Walpole, who had borrowed it from the then-Earl of Powis. Walpole called it “the most curious and entertaining book in the world,” and with good reason.

According to Herbert, the miniature was commissioned not by the Herberts but by the wife of one Sir John Ayres. She had purloined a copy of the original painting, now lost, and had Oliver make a version in miniature to wear “about her neck, so low that she hid it under her breasts,” a placement that Herbert acknowledges gave Sir John reasonable cause for suspicion. Then this happened:

Coming one day into her chamber, I saw her through the curtains lying upon her bed with a wax candle in one hand, and the picture I formerly mentioned in the other. I coming thereupon somewhat boldly to her, she blew out the candle, and hid the picture from me; myself thereupon being curious to know what that was she held in her hand, got the candle to be lighted again, by means whereof I found it was my picture she looked upon with more earnestness and passion than I could have easily believed, especially since myself was not engaged in any affection towards her.

Why, who could think there was illicit affection between them, just because he found himself in her rooms with the lights out while she fondled a miniature of him she kept in her cleavage? Sir John, apparently, because word got out that he planned to kill Herbert in his bed. When several titled personages alerted Edward Herbert to the contract out on his head, he enlisted his cousin Sir William Herbert to ask Sir John Ayres to refrain from murdering him in his sickbed until they could meet in an honorable duel once Edward was recovered from a fever.

The appeal fell on deaf ears, but their communication led Sir John to change his plans from murder in bed to murder on the streets. He and four men-at-arms attacked Herbert, recently recovered from his illness and on his way to Whitehall. A fierce battle ensued in which Herbert fended off five men, broke his sword, took a dagger blow from ribs to hip and still managed to pin Sir John down and whup him like he owed him money with the busted remnant of his sword. Ayres’ men dragged his body to safety.

Herbert recovered from his knife wound and wrote to Ayres again suggesting an honorable duel between them. Ayres replied that Herbert “had whored his wife, and that he would kill [him] with a musket out of a window.” The Privy Council got involved, adjudicating the dispute between them. Lady Ayres wrote a letter denying her husband’s allegations and the lords oohed and aahed over Herbert’s brave Dumas-like derring-do. Ayres did not try to kill him again.

Herbert recovered from his knife wound and wrote to Ayres again suggesting an honorable duel between them. Ayres replied that Herbert “had whored his wife, and that he would kill [him] with a musket out of a window.” The Privy Council got involved, adjudicating the dispute between them. Lady Ayres wrote a letter denying her husband’s allegations and the lords oohed and aahed over Herbert’s brave Dumas-like derring-do. Ayres did not try to kill him again.

What’s missing in this self-servingly dashing narrative is an explanation of how the portrait wound up with the Powis Herberts. Perhaps Lady Ayres handed it over. Perhaps this whole story is, let’s just say, richly embellished.

The miniature will now spend several months getting treatment from conservators. Once it is in tip-top shape, it may be loaned to other museums — the piece has been loaned to institutions like the Victoria & Albert in the past — before returning the Powis Castle for permanent display.

A team of paleontologists from Vienna’s Natural History Museum (NHM) has unearthed two large tusks and some vertebrae from a rare mammoth at a site 30 miles north of Vienna in the Weinviertel region of Lower Austria. The fossils were first discovered in mid-August by geologists surveying the site of a highway construction. They were studying the sediment layers when one of the geologists spotted an anomaly that turned out to be the tip of a tusk. The next day, experts from the NHM’s Geology and Palaeontology Department were called in to excavate the find and quickly unearthed a whole tusk and several vertebrae.

A team of paleontologists from Vienna’s Natural History Museum (NHM) has unearthed two large tusks and some vertebrae from a rare mammoth at a site 30 miles north of Vienna in the Weinviertel region of Lower Austria. The fossils were first discovered in mid-August by geologists surveying the site of a highway construction. They were studying the sediment layers when one of the geologists spotted an anomaly that turned out to be the tip of a tusk. The next day, experts from the NHM’s Geology and Palaeontology Department were called in to excavate the find and quickly unearthed a whole tusk and several vertebrae.  NHM paleontologists believe the tusks and vertebrae came from a single animal who died in the proto-Zaya river. The shape of the tusks and the sediment layer in which they were found suggest a preliminary date of around one million years ago. The fact that there was a river in which a mammoth’s remains could become embedded in the mud indicates it lived during an interglacial period, of which there were many during the 2.5 million years of the Pleistocene.

NHM paleontologists believe the tusks and vertebrae came from a single animal who died in the proto-Zaya river. The shape of the tusks and the sediment layer in which they were found suggest a preliminary date of around one million years ago. The fact that there was a river in which a mammoth’s remains could become embedded in the mud indicates it lived during an interglacial period, of which there were many during the 2.5 million years of the Pleistocene. most likely candidate. The descendents of a Siberian population of steppe mammoths evolved into the woolly mammoth about 400,000 years ago, so that might earn it the ur. Also the curved tusks seems most similar to those of Mammuthus trogontherii, to my entirely inexpert eyes.

most likely candidate. The descendents of a Siberian population of steppe mammoths evolved into the woolly mammoth about 400,000 years ago, so that might earn it the ur. Also the curved tusks seems most similar to those of Mammuthus trogontherii, to my entirely inexpert eyes.  further study. Researchers are excited to find out all they can, not just about the animal but its environment. Very few remains this old have been discovered in Austria, so there is much to be learned from them and the discovery context.

further study. Researchers are excited to find out all they can, not just about the animal but its environment. Very few remains this old have been discovered in Austria, so there is much to be learned from them and the discovery context.