A glass penny, the only known intact survivor of a World War II experiment, sold at auction Friday for $70,500 including buyer’s premium, more than twice its presale estimate of $30,000. The price was driven up in a bidding war between a phone buyer and one present in the room. The phone bidder, an American collector, won.

A glass penny, the only known intact survivor of a World War II experiment, sold at auction Friday for $70,500 including buyer’s premium, more than twice its presale estimate of $30,000. The price was driven up in a bidding war between a phone buyer and one present in the room. The phone bidder, an American collector, won.

The metals used to make pennies and nickels — copper, tin and nickel — were needed for the war effort so in 1942 the Treasury experimented with coins made from alternative raw materials. Private contractors, eight plastic manufacturers — Bakelite Corporation (Bloomfield, New Jersey), E.I. DuPont de Nemours & Co. (Arlington, New Jersey), Durez Plastics and Chemical, Inc. (North Tonawanda, New York), Patent Button Company Inc (Knoxville, Tennessee), Monsanto Chemical Company (Springfield, Massachusetts), Colt Patent Firearms Manufacturing Company (Hartford, Connecticut), Tennessee Eastman Corporation (Kingsport, Tennessee), Auburn Button Works (Auburn, New York) — and one glass company — Blue Ridge Glass Corporation (Kingsport, Tennessee) — were commissioned to strike coins with a variety of non-critical materials including Bakelite, other plastics, hard rubber, wood pulp and our hero today, glass.

The metals used to make pennies and nickels — copper, tin and nickel — were needed for the war effort so in 1942 the Treasury experimented with coins made from alternative raw materials. Private contractors, eight plastic manufacturers — Bakelite Corporation (Bloomfield, New Jersey), E.I. DuPont de Nemours & Co. (Arlington, New Jersey), Durez Plastics and Chemical, Inc. (North Tonawanda, New York), Patent Button Company Inc (Knoxville, Tennessee), Monsanto Chemical Company (Springfield, Massachusetts), Colt Patent Firearms Manufacturing Company (Hartford, Connecticut), Tennessee Eastman Corporation (Kingsport, Tennessee), Auburn Button Works (Auburn, New York) — and one glass company — Blue Ridge Glass Corporation (Kingsport, Tennessee) — were commissioned to strike coins with a variety of non-critical materials including Bakelite, other plastics, hard rubber, wood pulp and our hero today, glass.

Chief engraver John R. Sinnock created the pattern dies using simple designs. The obverse was a Liberty Head facing right, a copy of the head on the Colombian two centavos coin, with “LIBERTY” and “JUSTICE” on the left and right border and the date 1942 underneath the head. The reverse is a simple olive branch wreath designed by Anthony C. Paquet for a Washington medalet. Washington’s dates in the middle of the wreath were replaced with “UNITED STATES MINT.”

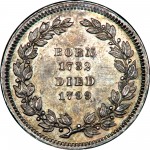

Chief engraver John R. Sinnock created the pattern dies using simple designs. The obverse was a Liberty Head facing right, a copy of the head on the Colombian two centavos coin, with “LIBERTY” and “JUSTICE” on the left and right border and the date 1942 underneath the head. The reverse is a simple olive branch wreath designed by Anthony C. Paquet for a Washington medalet. Washington’s dates in the middle of the wreath were replaced with “UNITED STATES MINT.”

The dies were sent to the manufacturers who struck prototype cents with their experimental materials. The Blue Ridge Glass Corporation struck their pennies on amber tempered glass blanks from Corning Glass Co.

The dies were sent to the manufacturers who struck prototype cents with their experimental materials. The Blue Ridge Glass Corporation struck their pennies on amber tempered glass blanks from Corning Glass Co.

Blue Ridge had considerable difficulty making glass 1942 sample coins. For impressing a design into glass, both glass and the dies had to be very hot — just below glass melting temperature — then the glass had to cool quickly to preserve design detail. But Blue Ridge was not able to heat the die, and the resulting experimental cents were softly detailed and had many minute surface imperfections. Blue Ridge described their process and results in a six-page report, which has been preserved among U.S. Mint documents in the National Archives.

The surface of the glass coins was susceptible to crazing — clearly visible in the “UNITED STATES MINT” on the reverse of the penny that was just sold — but at first that didn’t trouble the Treasury Department. Blue Ridge was led to believe they’d get a contract to produce the glass pennies and even began to expand their facilities and plan the additional security necessary for mint work. Then, all of a sudden, Blue Ridge’s president J.H. Lewis was informed by Treasury that the project was called off. He was not told why.

Official records indicate Treasury thought the glass coinage would be “too brittle,” but that was just a smokescreen. The real reason was as top secret as it gets. The planned production line glass pennies would have contained traces of uranium oxide that would make them fluoresce under ultraviolet light, a cool and ingenious anti-counterfeiting system. But another project that started in 1942 required every molecule of fissionable material that could be scrounged up, so the glass coins were scrapped and Blue Ridge had to send all of its uranium stock to Oak Ridge for use in the Manhattan Project.

None of the plastic, rubber and glass experiments ever went into production. The Treasury doubted if plastic would ever be accepted by the public as legitimate currency and anyway the most successful plastics, urea and phenol, soon made the critical materials list themselves. The glass penny with its poor impressions and secretly invaluable uranium wouldn’t do either. Alternative metals won the day. The wartime penny would be zinc coated steel. It was minted in 1943. For a year it was lighter than the standard 3.11-gram Lincoln Wheat penny that preceded it, weighing 2.7 grams. Starting in 1944, the weight was back up to 3.11 grams and copper was back in the mix with zinc.

None of the plastic, rubber and glass experiments ever went into production. The Treasury doubted if plastic would ever be accepted by the public as legitimate currency and anyway the most successful plastics, urea and phenol, soon made the critical materials list themselves. The glass penny with its poor impressions and secretly invaluable uranium wouldn’t do either. Alternative metals won the day. The wartime penny would be zinc coated steel. It was minted in 1943. For a year it was lighter than the standard 3.11-gram Lincoln Wheat penny that preceded it, weighing 2.7 grams. Starting in 1944, the weight was back up to 3.11 grams and copper was back in the mix with zinc.

Very few of the experimental coins still exist today. The Mint destroyed most of them. A few examples managed to avoid that fate, mostly reddish plastic ones. Only one other glass example is known to have survived, and it is broken in half.