This year The History Blog celebrated its 10th anniverary. The Six Million Dollar Man didn’t make an appearance at this party like he did at the Six Millionth View party last year, but we made up for it with a really great comment thread. I love when readers who rarely (or never!) comment mingle with the regular commenters to say nice things about the blog. It’s downright invigorating. (No, that is not a prompt for more of same in the comments on this post. Okay it kind of is. Not that you need prompting.)

It’s the on-topic posts that capture people’s attention on the larger web. The article about the 17th century silk gown found on the Texel shipwreck was the runaway most visited of the year with 11,555 views. The story of the murder of Joe the Quilter and the discovery of the remains of his cottage was the second most popular of the year with 6,276 views. It was also one of my favorites. The tragic story, Joe’s outstanding artisanship, the rare survival of a labourer’s cottage from the 1820s and my first encounter with the Beamish Museum all captivated my attention. Then the modern Joe the Quilter topped it all off by commenting.

It’s the on-topic posts that capture people’s attention on the larger web. The article about the 17th century silk gown found on the Texel shipwreck was the runaway most visited of the year with 11,555 views. The story of the murder of Joe the Quilter and the discovery of the remains of his cottage was the second most popular of the year with 6,276 views. It was also one of my favorites. The tragic story, Joe’s outstanding artisanship, the rare survival of a labourer’s cottage from the 1820s and my first encounter with the Beamish Museum all captivated my attention. Then the modern Joe the Quilter topped it all off by commenting.

That wasn’t the only murderous story of the year. I was particularly interested in the story of Martha Brown, the woman who killed her abusive husband and was hanged for it. Among the thousands of people who attended her execution was a 16-year-old Thomas Hardy. Years later he would write Tess of the d’Urbervilles about a woman who kills her abuser and is hanged for murder. The century-old cold case of the Fontaubert bones only has the legend of a gloriously lurid murder behind it, but maybe the new forensic investigation will turn up something if not equally interesting, at least mildly so. Then there was the first known boomerang victim, killed in the 13th century by a fighting boomerang, a heavy, sharp-edged wood weapon that cut through his bone like metal. I’m still keeping my fingers crossed that the remains of the victim of a huge 17th century royal sex scandal have been found, but the odds are slim.

That wasn’t the only murderous story of the year. I was particularly interested in the story of Martha Brown, the woman who killed her abusive husband and was hanged for it. Among the thousands of people who attended her execution was a 16-year-old Thomas Hardy. Years later he would write Tess of the d’Urbervilles about a woman who kills her abuser and is hanged for murder. The century-old cold case of the Fontaubert bones only has the legend of a gloriously lurid murder behind it, but maybe the new forensic investigation will turn up something if not equally interesting, at least mildly so. Then there was the first known boomerang victim, killed in the 13th century by a fighting boomerang, a heavy, sharp-edged wood weapon that cut through his bone like metal. I’m still keeping my fingers crossed that the remains of the victim of a huge 17th century royal sex scandal have been found, but the odds are slim.

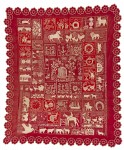

I allowed myself some shameless photographic indulgences this year. The Australian quilts were probably my richest haul in a single post, but in sheer size and beauty, the Dream Garden Tiffany mosaic gets very high ranking in the end of the year summary even though I only just posted it a couple of days ago. Another December entry gave me my greatest source of photographic gluttony, however. It’s the boxwood miniatures. When the Art Gallery of Ontario gave me access to their folder of high resolution photographs, I seriously got a rush. It’s because the carving is so, so small. Having gigantic pictures where the details could be seen in extreme close-up totally made my year.

I allowed myself some shameless photographic indulgences this year. The Australian quilts were probably my richest haul in a single post, but in sheer size and beauty, the Dream Garden Tiffany mosaic gets very high ranking in the end of the year summary even though I only just posted it a couple of days ago. Another December entry gave me my greatest source of photographic gluttony, however. It’s the boxwood miniatures. When the Art Gallery of Ontario gave me access to their folder of high resolution photographs, I seriously got a rush. It’s because the carving is so, so small. Having gigantic pictures where the details could be seen in extreme close-up totally made my year.

Along similar lines, I love how high resolution 3D scans of artifacts and remains are becoming more common. This year alone we saw 3D scans of Chinese oracle bones, the Dandaleith Pictish stone, a Pictish cross slab, an Anglo-Saxon name stone found at Lindisfarne, bones and objects from the Tudor flagship Mary Rose, the first church where Norway’s Viking saint king Olaf II was buried and the irrepressible charm of the Skara Brae “Buddo” figurine.

Along similar lines, I love how high resolution 3D scans of artifacts and remains are becoming more common. This year alone we saw 3D scans of Chinese oracle bones, the Dandaleith Pictish stone, a Pictish cross slab, an Anglo-Saxon name stone found at Lindisfarne, bones and objects from the Tudor flagship Mary Rose, the first church where Norway’s Viking saint king Olaf II was buried and the irrepressible charm of the Skara Brae “Buddo” figurine.

Some of my favorite finds of the year were inscriptions. There was the Etruscan stele found in the foundations of an ancient temple in Tuscany, later found to include the name of the goddess Uni. Newly discovered Etruscan inscriptions are always cause for celebration, and this one is very long and very old. I also loved the two from modern-day Turkey, the 2,000-year-old horse racing rules and the amazing 2,200-year-old lease contract. It’s a contract! Literally carved in stone! And thus metaphor becomes literal.

Some of my favorite finds of the year were inscriptions. There was the Etruscan stele found in the foundations of an ancient temple in Tuscany, later found to include the name of the goddess Uni. Newly discovered Etruscan inscriptions are always cause for celebration, and this one is very long and very old. I also loved the two from modern-day Turkey, the 2,000-year-old horse racing rules and the amazing 2,200-year-old lease contract. It’s a contract! Literally carved in stone! And thus metaphor becomes literal.

With no particular thread connecting them other than my personal interest, I got a big kick out of discoveries from all over the world. There was that group of small ceremonial iron weapons found in Oman, the small fragment of 13th century pottery from Teruel, Spain, decorated with a unique depiction of a Jewish man, the Tuscan villa of Vettius Agorius Praetextatus, a 4th century senator and one of the last politically prominent adherents of traditional Roman religion to fight for its preservation, that freaking huge gold torc found in Cambridgeshire and the unbearable cuteness of the Canaanite “Thinker” figurine.

With no particular thread connecting them other than my personal interest, I got a big kick out of discoveries from all over the world. There was that group of small ceremonial iron weapons found in Oman, the small fragment of 13th century pottery from Teruel, Spain, decorated with a unique depiction of a Jewish man, the Tuscan villa of Vettius Agorius Praetextatus, a 4th century senator and one of the last politically prominent adherents of traditional Roman religion to fight for its preservation, that freaking huge gold torc found in Cambridgeshire and the unbearable cuteness of the Canaanite “Thinker” figurine.

In the ephemera category, the only copy of Utrecht’s first newspaper, published in 1623, was found in a hand-bound anthology in the City Archives and Athenaeum Library in Deventer, the Netherlands. The news wasn’t fresh (even our Dutch-speaking readers struggled to follow it), but the history of newspapers was entirely unknown to me before I researched the find. Fascinating subject. The account of another battle of Thermopylae, this one between invading Goths and a combined Roman-Greek force during the 3rd century Gothic wars, discovered in a palimpsest in Vienna is a stand-out of the year. It’s a previously unknown passage in the Scythica, a history of the wars written by Athenian historian P. Herennius Dexippus who lived through them. Only a few fragments from this history survived quoted in later books. The palimpsest gave us by far the longest surviving passage, and a riveting one at that.

In the ephemera category, the only copy of Utrecht’s first newspaper, published in 1623, was found in a hand-bound anthology in the City Archives and Athenaeum Library in Deventer, the Netherlands. The news wasn’t fresh (even our Dutch-speaking readers struggled to follow it), but the history of newspapers was entirely unknown to me before I researched the find. Fascinating subject. The account of another battle of Thermopylae, this one between invading Goths and a combined Roman-Greek force during the 3rd century Gothic wars, discovered in a palimpsest in Vienna is a stand-out of the year. It’s a previously unknown passage in the Scythica, a history of the wars written by Athenian historian P. Herennius Dexippus who lived through them. Only a few fragments from this history survived quoted in later books. The palimpsest gave us by far the longest surviving passage, and a riveting one at that.

Denmark may win the award this year for most exciting finds in one country. There was the wee gold pendant found by a metal detectorist that is the earliest figure of Christ found in Denmark, the lead amulet invoking elves and the Christian Trinity, the rediscovery of the long-lost Ydby Runestone, the stabby beauty of the Viking treasure hoard found in Lille Karleby, the

Denmark may win the award this year for most exciting finds in one country. There was the wee gold pendant found by a metal detectorist that is the earliest figure of Christ found in Denmark, the lead amulet invoking elves and the Christian Trinity, the rediscovery of the long-lost Ydby Runestone, the stabby beauty of the Viking treasure hoard found in Lille Karleby, the

two pounds of Viking gold bangles, the Viking toolbox unearthed at Borgring, and that amazingly smooth giant Neolithic flint axe. But of all the great and wondrous treasures Denmark has brought us this year, the greatest of them all was the 17th century bishop’s turd. The title alone made me laugh for a solid two days.

The hoards of the Danes had sturdy competition this year from Spain and Switzerland. The sheer quantity, 1,300 pounds of Roman coins, found in Tomares outside Seville, Spain, would have been impressive enough on its own, but they came in custom matching amphorae of a type never seen before. Researchers are still going through the tens of thousands of coins from the late 3rd, early 4th century. It’s not cash or pounds of gold, but the Roman lamp hoard found in Switzerland stands next to these glories with its head held high, just because it’s so pristine and unique.

The hoards of the Danes had sturdy competition this year from Spain and Switzerland. The sheer quantity, 1,300 pounds of Roman coins, found in Tomares outside Seville, Spain, would have been impressive enough on its own, but they came in custom matching amphorae of a type never seen before. Researchers are still going through the tens of thousands of coins from the late 3rd, early 4th century. It’s not cash or pounds of gold, but the Roman lamp hoard found in Switzerland stands next to these glories with its head held high, just because it’s so pristine and unique.

I think the highlight of the year, maybe the highlight of the first decade of The History Blog history, was the chilling Halloween three-parter about the Harrison Horror (part I, part II, part III). I’d been thinking about writing a serial for years, and a long-form treatment of the body-snatching of John Scott Harrison and Augustus Devin for at least two years. I finally did it and it was so, so worth it. I’m warning you, though, there is no way I’m even trying to top it next year, not for Halloween anyway. Maybe some other theme will inspire me, or maybe it’ll just be something that I randomly stumble across. Stay tuned to find out!

I think the highlight of the year, maybe the highlight of the first decade of The History Blog history, was the chilling Halloween three-parter about the Harrison Horror (part I, part II, part III). I’d been thinking about writing a serial for years, and a long-form treatment of the body-snatching of John Scott Harrison and Augustus Devin for at least two years. I finally did it and it was so, so worth it. I’m warning you, though, there is no way I’m even trying to top it next year, not for Halloween anyway. Maybe some other theme will inspire me, or maybe it’ll just be something that I randomly stumble across. Stay tuned to find out!

I wish you all the very best of New Years, full of prosperity, peace and nerdery. I will continue to do my utmost to contribute to the last of those.