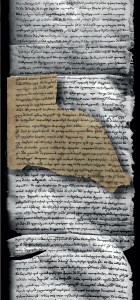

Archaeologists have unearthed a vast collection of pottery (pdf) during construction of Crossrail’s new Elizabeth line station at Tottenham Court Road in London. The station is being built on the site of the former Crosse & Blackwell factory at Soho Square, where some of Britain’s most popular sauces, condiments and jams were manufactured from 1838 until 1921. The basements of the bottling warehouse were unexpectedly well-preserved. Kilns, furnaces and a refrigeration system were discovered in the warren of underground rooms. More than 13,000 pots, jars and bottles of pickle, mustard and jam were found in a cistern on the site. While many of them were broken, there were an impressive number of intact, unused pieces of ceramic, stoneware and glass.

Archaeologists have unearthed a vast collection of pottery (pdf) during construction of Crossrail’s new Elizabeth line station at Tottenham Court Road in London. The station is being built on the site of the former Crosse & Blackwell factory at Soho Square, where some of Britain’s most popular sauces, condiments and jams were manufactured from 1838 until 1921. The basements of the bottling warehouse were unexpectedly well-preserved. Kilns, furnaces and a refrigeration system were discovered in the warren of underground rooms. More than 13,000 pots, jars and bottles of pickle, mustard and jam were found in a cistern on the site. While many of them were broken, there were an impressive number of intact, unused pieces of ceramic, stoneware and glass.

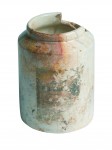

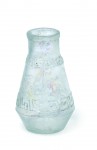

The finds include glass bottles for Mushroom Catsup, ceramic bung jars for mustard and Piccalilli and delicately painted white jars for Preserved Ginger. Archaeologists also found white earthenware jars for Pure Orange Marmalade, Household Raspberry Jam and Plum Jam, some of which still bare their original labels. They illustrate the ambitions of one of Victorian Britain’s most prolific and enduring enterprises and evidence the development of British tastes.

Nigel Jeffries, [Museum of London Archeaology]’s Medieval and Later Pottery Specialist and author of the book, said: “Excavations on Crosse & Blackwell’s Soho factory produced a large and diverse collection of pottery and glass related to their products, with one cistern alone containing nearly three tonnes of Newcastle made marmalade jars with stoneware bottles and jars. We think this is the biggest collection of pottery ever discovered in a single feature from an archaeological site in London.”

The company began under the name Jackson in the early 18th century. It was changed to West & Wyatt in 1819. West & Wyatt had a shop at 21 Soho Square where they sold soup, pâté, pickles and sauces to the wealthy and titled. That same year two apprentices were hired: Edmund Crosse and Thomas Blackwell. Like something out of The Secret of My Success, Crosse and Blackwell climbed the ladder with impressive speed until just 10 years later they bought the company lock, stock and barrel for £600 and changed its name to a brand that would soon become renown around the world for canned foods, sauces and condiments. The Soho Square shop became an ever-expanding bottling factory.

The company began under the name Jackson in the early 18th century. It was changed to West & Wyatt in 1819. West & Wyatt had a shop at 21 Soho Square where they sold soup, pâté, pickles and sauces to the wealthy and titled. That same year two apprentices were hired: Edmund Crosse and Thomas Blackwell. Like something out of The Secret of My Success, Crosse and Blackwell climbed the ladder with impressive speed until just 10 years later they bought the company lock, stock and barrel for £600 and changed its name to a brand that would soon become renown around the world for canned foods, sauces and condiments. The Soho Square shop became an ever-expanding bottling factory.

Crosse & Blackwell were one of the first companies to secure a Royal Warrant from Queen Victoria in 1837, the year of her accession to the throne when she was 18 years old. They were also pioneers in the use of celebrity chef as endorsers and collaborators. In the late 1840s, Alexis Soyer, high society chef, inventor, cookbook author, soup kitchen innovator and the most famous culinary genius of his time, created the tangy Soyer’s Sauce sold by Crosse & Blackwell in two versions: a stronger “Soyer’s Sauce for Gentlemen” and a milder “Soyer’s Sauce for Ladies.” They quickly became bestsellers. He followed up with “Soyer’s Relish,” which was the bestselling sauce in London in 1849 and would be sold by Crosse & Blackwell for more than 70 years, and “Soyer’s Sultana’s Sauce.”

Crosse & Blackwell were one of the first companies to secure a Royal Warrant from Queen Victoria in 1837, the year of her accession to the throne when she was 18 years old. They were also pioneers in the use of celebrity chef as endorsers and collaborators. In the late 1840s, Alexis Soyer, high society chef, inventor, cookbook author, soup kitchen innovator and the most famous culinary genius of his time, created the tangy Soyer’s Sauce sold by Crosse & Blackwell in two versions: a stronger “Soyer’s Sauce for Gentlemen” and a milder “Soyer’s Sauce for Ladies.” They quickly became bestsellers. He followed up with “Soyer’s Relish,” which was the bestselling sauce in London in 1849 and would be sold by Crosse & Blackwell for more than 70 years, and “Soyer’s Sultana’s Sauce.”

The company also jumped on the opportunity to introduce Indian flavors to their product line. A Crosse & Blackwell employee went to India with the first troops sent by the East India Company. He came back with recipes that would shortly become Captain White’s Oriental Pickle and Curry Powder and Abdool Fygo’s Chutney.

Crosse & Blackwell was an official wholesaler of another India-inspired condiment that is still a top seller today: Lea & Perrins Worcestershire Sauce. You’d think with a name like Worcestershire it would have an English origin, but in fact, the recipe was brought back from India to Worcester by Lord Marcus Sandys in 1835. Sandys had the local pharmacists cook him up a batch but it tasted terrible, so the chemists, Messrs. John Lea and William Perrin, stashed the barrel in the cellar and forgot about for two years. In 1837 they noticed the barrel in the cellar and gave the contents another taste. They were stunned by how delicious it was. They bought the rights to the recipe from Lord Sandys and in 1838 introduced the pantry staple that makes my mom’s stuffed celery so great.

Crosse & Blackwell was an official wholesaler of another India-inspired condiment that is still a top seller today: Lea & Perrins Worcestershire Sauce. You’d think with a name like Worcestershire it would have an English origin, but in fact, the recipe was brought back from India to Worcester by Lord Marcus Sandys in 1835. Sandys had the local pharmacists cook him up a batch but it tasted terrible, so the chemists, Messrs. John Lea and William Perrin, stashed the barrel in the cellar and forgot about for two years. In 1837 they noticed the barrel in the cellar and gave the contents another taste. They were stunned by how delicious it was. They bought the rights to the recipe from Lord Sandys and in 1838 introduced the pantry staple that makes my mom’s stuffed celery so great.

Crosse & Blackwell is repeatedly mentioned in Lea & Perrin’s 19th century ads as a purveyor of “the only good sauce,” but the excavation revealed that the Crosse & Blackwell factory was also involved on the production side. Lea & Perrins branded glass stoppers were unearthed at the factory site.

The Museum of London Archeaology (MOLA) has published a book about the factory finds. Crosse and Blackwell 1830–1921: a British food manufacturer in London’s West End is part six of MOLA’s Crossrail Archaeology series, 10 publications that explore different aspects of the unprecedented archaeological project engendered by the construction of new subway lines and stations. You can buy it online for a tenner.

The Museum of London Archeaology (MOLA) has published a book about the factory finds. Crosse and Blackwell 1830–1921: a British food manufacturer in London’s West End is part six of MOLA’s Crossrail Archaeology series, 10 publications that explore different aspects of the unprecedented archaeological project engendered by the construction of new subway lines and stations. You can buy it online for a tenner.