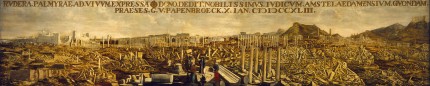

Palmyra, the crossroads of civilizations, prosperous center of trade between the Silk Road and Europe from the 3rd century B.C. under the Hellenistic Seleucid kingdom through the 3rd century A.D. under the Roman Empire, is no stranger to wartime destruction. Emperor Aurelian razed the city in 273 when it rebelled against his rule. He pillaged its temples and used their treasures to decorate his temple to the sun god Sol in Rome. Enough survived to make Palmyra’s monumental ruins some of the most extensive and dramatic in the Greco-Roman world, and when European visitors started writing about the spectacular remains starting in 1696 with Abednego Seller’s The Antiquities of Palmyra, Palmyrene structures like the Temple of Bel, the Temple of Baalshamin, the tower tombs and the Great Colonnade became icons of classical architecture and inspired Western artists, poets and architects.

One of those artists was Louis-François Cassas (1756-1827) who made highly detailed drawings of the ruins of Palmyra in 1785. Cassas spent a month in Palmyra, recording all of the ancient ruins he saw. As an architect, Cassas had a keen eye for sculptural features which gave his renderings a precision matched by none of his predecessors in the voyage pittoresque tradition of illustrated travel accounts. His drawings of Palmyra, detailed views of ornamental features, architectural elevations and reconstructions illustrated his own travel account, Voyage Pittoresque de la Syrie, de la Phenicie, de la Palestine, et de la Basse Egypte, published beginning in 1799.

One of those artists was Louis-François Cassas (1756-1827) who made highly detailed drawings of the ruins of Palmyra in 1785. Cassas spent a month in Palmyra, recording all of the ancient ruins he saw. As an architect, Cassas had a keen eye for sculptural features which gave his renderings a precision matched by none of his predecessors in the voyage pittoresque tradition of illustrated travel accounts. His drawings of Palmyra, detailed views of ornamental features, architectural elevations and reconstructions illustrated his own travel account, Voyage Pittoresque de la Syrie, de la Phenicie, de la Palestine, et de la Basse Egypte, published beginning in 1799.

Following in Cassas footprints but using a new medium was Louis Vignes (1831-1896), a French career naval officer and a photographer. In 1863, Vignes was assigned to accompany Honoré Théodore d’Albert, duc de Luynes, on a scientific expedition to Palestine, Syria and Lebanon. Luynes was an avid amateur archaeologist and antiquarian, an expert in Damascus steel and a patron of the arts with a particular taste for commissioning works in the classical style. The year before the expedition, the duke had donated his vast collection of antiquities — coins, Greek vases, medallions, intaglio gemstones — to France’s Cabinet des Médailles, and as an immensely wealthy aristocrat with a passel of big titles, when Luynes demanded that the French government provide him with a naval officer for his voyage, he got what he wanted.

Following in Cassas footprints but using a new medium was Louis Vignes (1831-1896), a French career naval officer and a photographer. In 1863, Vignes was assigned to accompany Honoré Théodore d’Albert, duc de Luynes, on a scientific expedition to Palestine, Syria and Lebanon. Luynes was an avid amateur archaeologist and antiquarian, an expert in Damascus steel and a patron of the arts with a particular taste for commissioning works in the classical style. The year before the expedition, the duke had donated his vast collection of antiquities — coins, Greek vases, medallions, intaglio gemstones — to France’s Cabinet des Médailles, and as an immensely wealthy aristocrat with a passel of big titles, when Luynes demanded that the French government provide him with a naval officer for his voyage, he got what he wanted.

Vignes was a particularly good choice for a mission that would encounter numerous archaeological remains, because he had been trained by pioneering photographer Charles Nègre and could be of as much help to the duke on dry land as he was on the seas. Luynes’ primary objective was to do one of the first scientific explorations of the Dead Sea. From the Dead Sea, the expedition traveled the Jordan River Valley, the mountains of Moab and the full length of the Wadi Arabah to the Gulf of Aqaba. Over the 10 months of the expedition, they also visited Palmyra and Beirut where Vignes took pictures of the ancient ruins.

Vignes was a particularly good choice for a mission that would encounter numerous archaeological remains, because he had been trained by pioneering photographer Charles Nègre and could be of as much help to the duke on dry land as he was on the seas. Luynes’ primary objective was to do one of the first scientific explorations of the Dead Sea. From the Dead Sea, the expedition traveled the Jordan River Valley, the mountains of Moab and the full length of the Wadi Arabah to the Gulf of Aqaba. Over the 10 months of the expedition, they also visited Palmyra and Beirut where Vignes took pictures of the ancient ruins.

The scientific report of the expedition, Voyage d’exploration à la mer Morte, à Petra, et sur la rive gauche du Jourdain, wasn’t published until 1875, eight years after Luynes’ death. Vignes photos of the Dead Sea were included in the publication, but by then Vignes had long since cut to the chase. He hooked up with his old mentor Charles Nègre to develop and print the negatives Vignes had taken in Beirut and Palmyra. The albumen prints were given to the duc de Luynes before his death in 1867. The Vignes photographs are the earliest known pictures of the Greco-Roman remains in Palmyra.

The scientific report of the expedition, Voyage d’exploration à la mer Morte, à Petra, et sur la rive gauche du Jourdain, wasn’t published until 1875, eight years after Luynes’ death. Vignes photos of the Dead Sea were included in the publication, but by then Vignes had long since cut to the chase. He hooked up with his old mentor Charles Nègre to develop and print the negatives Vignes had taken in Beirut and Palmyra. The albumen prints were given to the duc de Luynes before his death in 1867. The Vignes photographs are the earliest known pictures of the Greco-Roman remains in Palmyra.

They have taken on even more significance in the light of recent events. Palmyra’s ruins have been devastated in the Syrian Civil War, bombed and shelled by everyone, deliberately destroyed by IS ostensibly out of iconoclastic fervor, although their real motivation, I think, is to taunt the world into multiple impotent rage strokes; cultural heritage destruction as a brutal mass troll. The temples of Bel and Baalshamin were blown up, as were three of the best preserved tower tombs, the Arch of Triumph on the east end of the Great Colonnade and, if recent reports bear out, the tetrapylon and part of the Roman theater.

They have taken on even more significance in the light of recent events. Palmyra’s ruins have been devastated in the Syrian Civil War, bombed and shelled by everyone, deliberately destroyed by IS ostensibly out of iconoclastic fervor, although their real motivation, I think, is to taunt the world into multiple impotent rage strokes; cultural heritage destruction as a brutal mass troll. The temples of Bel and Baalshamin were blown up, as were three of the best preserved tower tombs, the Arch of Triumph on the east end of the Great Colonnade and, if recent reports bear out, the tetrapylon and part of the Roman theater.

In 2015, with the monstrous savaging of Palmyra’s ancient monuments well underway, the Getty Research Institute acquired an album of 47 of Vignes’ original photos taken in Palmyra and Beirut. That album was digitized — the pictures can be browsed here — as were 58 additional Vignes prints from the duc de Luynes’ personal collection.

In 2015, with the monstrous savaging of Palmyra’s ancient monuments well underway, the Getty Research Institute acquired an album of 47 of Vignes’ original photos taken in Palmyra and Beirut. That album was digitized — the pictures can be browsed here — as were 58 additional Vignes prints from the duc de Luynes’ personal collection.

Now the Getty Research Institute has enlisted its Vignes photographs, Cassas drawings and other important sources in an online exhibition dedicated to history of Palmyra.

Now the Getty Research Institute has enlisted its Vignes photographs, Cassas drawings and other important sources in an online exhibition dedicated to history of Palmyra.

The online exhibition draws heavily from the Getty Research Institute’s collections as well as art in museum and library collections all over the world. The exhibition explores the site’s early history, the far-reaching influence of Palmyra in Western art and culture, and the loss, now tremendous and irrevocable, of the ruins that for centuries stood as a monument to a great city and her people.

“The devastation unleashed in Syria today forces a renewed interpretation of the early prints and photographs of this extraordinary world heritage site.” said Getty Research Institute curator Frances Terpak. “They gain more significance as examples of cultural documents that

can encourage a deeper appreciation of humanity’s past achievements. Understanding Palmyra through these invaluable accounts preserves its memory and connects us with its grandeur and enduring legacy.”

The Legacy of Ancient Palmyra is the Getty Research Institute’s first online exhibition and it’s beautifully curated. I hope it’s the first of many to come.