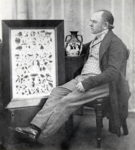

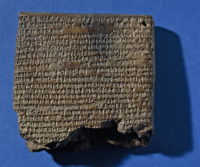

If you thought Irving Finkel, the British Museum’s Middle East curator and foremost cuneiform expert, outdid himself in that video where he played the Royal Game of Ur, you’re going to love his Halloween themed video. In it he summarizes in his characterstically witty style the inscructions for necromancy, raising the dead for the purpose of foretelling the future, found on a tablet (K.2779) in the British Museum.

Written in Neo-Babylonian in the 7th century B.C., the tablet was one of tens of thousands discovered at Nineveh that were part of what is known as the Library of Ashurbanipal. Only the top half of it and a few fragments have survived so we don’t have the full recipe for conjuring the spirits of the dead, sad to say, and there are a few lines of magical incantantions that are untranslatable because they were written in what scholars think may be a mixed-up kind of Sumerian seeing as by the 1st milennium B.C. nobody could speak the real thing anymore. This kind of magic-speak has been found on tablets before, including ones dealing with necromancy.

There aren’t a great many specifically dedicated to the raising of ghosts and questioning them, interestingly enough. The namburbi genre this tablet is a part of usually deals with warnings and magic to repel ghosts and contain the damage they can do. Tablet 2779 is unusual in that it covers both subjects: how to raise the ghost and then how to prevent its evil from harming the home and its residents. As it was not incised in Nineveh, it’s likely the tablet was brought to the library in a deliberate attempt to flesh out the collection in subject areas that were sparsely covered.

Here’s a translation of the surviving cuneiform from K.2279, minus the couple of lines of untranslatable verse:

Here’s a translation of the surviving cuneiform from K.2279, minus the couple of lines of untranslatable verse:

An incantation to enable a man to see a ghost.

Its ritual: (you crush) mouldy wood, fresh leaves of Euphrates poplar in water, oil, beer (and) wine. You dry, crush and sieve snake-tallow, lion-tallow, crab-tallow, white honey, a frog (that lives) among the pebbles, hair of a dog, hair of a cat, hair of a fox, bristle of a chameleon (and) bristle of a (red) lizard, “claw” of a frog, end-of-intestines of a frog, the left wing of a grasshopper, (and) marrow from the long bone of a goose. You mix (all this) (in) wine, water (and) milk with amhara plant. You recite the incantation three times and you anoint your eyes (with it) and you will see the ghost: he will speak with you. You can look at the ghost: he will talk with you.

In order to avert the evil (inherent) in a ghost’s cry you (sic) crush a potsherd from a ruined tell in water. He should sprinkle the house (with this water). For three days he should make offerings to the family ghosts.

He should pour out beer (flavoured with) roast barley. He should scatter juniper over a censer before Samas, pour out prime beer, offer a resent to Samas, and recite as follows:

O Samas, Judge of Heaven and Underworld, Foremost One of the Anunnaki!

O Samas, Judge of all the Lands, Samas Foremost and Resplendent One!

You keep them in check, O Samas, the Judge. You carry those from Above down to Below,

Those from Below up to Above. The ghost who has cried out in my house, whether of (my) father or mother, whether (my) brother or sister,

Whether a forgotten son of someone, whether a vagrant ghost show has no-one to care for it,

An offering has been made for him! Water has been poured out for him! May the evil in his cry away behin him!

Let the evil in his evil cry not come near me! <…> You do this repeatedly for three days, and <…>You wash his hands, you anoint him with U.SIKIL: “It is finished”: in oil.

I love that they pour out beer for him. Very 90s rap.

The only negative thing I can say about Finkel’s explanation of the tablet is that it’s way too short. I’m hoping he does what he did with Ur and films himself actually performing the ritual. He’s already scared up a suitable skull (Mesopotamian, one hopes, although there is nothing in the literature that suggests the skulls used in these rituals needed to have belonged to any specific individual, group or time period). It’s just the ingredients for the magical brew he’s having difficulty obtaining. That, Dr. Finkel, is what the Internet is for. All you need is a little viral luck and within days you will be inundated with sufficient snake tallow, frog end-of-intestines and chameleon bristles to raise an army of the dead.