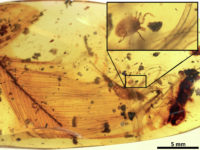

The rich deposits of amber mined in Myanmar (formerly Burma) have produced another stellar example of Cretaceous creatures frozen in a dramatic and scientifically significant posture. Earlier this year researchers found the remains of a baby avian dinosaur of the enantiornithes species which was uniquely well-preserved having spent 99 million years encased in amber. The discovery shed new light on the animal’s growth and development, and now the same can be said for a long-extinct tick. A nymph tick of the Cornupalpatum burmanicum species has been found in resin caught in the act of grabbing onto the feather of an avian dinosaur.

The rich deposits of amber mined in Myanmar (formerly Burma) have produced another stellar example of Cretaceous creatures frozen in a dramatic and scientifically significant posture. Earlier this year researchers found the remains of a baby avian dinosaur of the enantiornithes species which was uniquely well-preserved having spent 99 million years encased in amber. The discovery shed new light on the animal’s growth and development, and now the same can be said for a long-extinct tick. A nymph tick of the Cornupalpatum burmanicum species has been found in resin caught in the act of grabbing onto the feather of an avian dinosaur.

Modern ticks feast mightily on the blood of mammals, but their ancestors didn’t have the smorgasbord of mammal species to enjoy that exist on the planet today. Mammals only got so numerous, large and varied after the Cretaceous–Paleogene mass extinction event 65 million years ago. What animals were their primary source of food in the Cretaceous? Most scientists thought reptiles, amphibians and the little mammals that were scurrying about at the time were likely sources. For one thing, there were enough of them to support an extensive parasitic population, unlike avian dinosaurs.

Researcher Ricardo Pérez-de la Fuente at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History thought the avialans worth exploring as prospective tick drive-thrus, and spent years studying ticks trapped in amber for evidence of their environment.

The tick-and-feather pair support a theory that Pérez-de la Fuente had already spent years developing, based on other ticks trapped in amber from the same period. Those ticks didn’t have dinosaur feathers encased with them, but there were little hairs. The hairs resemble those left behind by a type of beetle larva that, today, lives in bird nests.

“We had this indirect evidence about the relationship between ticks and feathered dinosaurs,” Pérez-de la Fuente says, but the researchers didn’t have any direct evidence for the relationship until they saw the tick and feather trapped together in amber. […]

Now, just because there’s a feather and a tick holding on to it during the resin flood that would kill it doesn’t make it incontrovertible proof that they fed off the avian dinosaurs. Other animals lived in nests (viz the above-mentioned beetle larva) and the feather could be an accidental floater that seems more suggestive than it is.

Pérez-de la Fuente acknowledges there is more work to be done to clarify the ancient origins of ticks and their blood-sucking behaviors. For example, one amber specimen contains a tick engorged with blood, but Pérez-de la Fuente and his co-authors couldn’t figure out how to analyze that blood because the tick wasn’t entirely encased in amber, so the iron in the blood was contaminated with minerals.

USE FROG DNA!11 What could possibly go wrong? Seriously, being able to purify and analyze prehistoric blood, even blood that has been contaminated environmentally, would open up intriguing new avenues of exploration. Give the leaps in analytic and DNA technology over the past few decades, it’s not inconceivable that someone will figure out how to study the blood of these kinds of specimens.

USE FROG DNA!11 What could possibly go wrong? Seriously, being able to purify and analyze prehistoric blood, even blood that has been contaminated environmentally, would open up intriguing new avenues of exploration. Give the leaps in analytic and DNA technology over the past few decades, it’s not inconceivable that someone will figure out how to study the blood of these kinds of specimens.

Interesting side note: we don’t know exactly where in Myanmar the amber ticks used in the study were found. The specimens were sold online to private collectors, but in something of a watershed event, one collector donated his amber to the American Museum of Natural History in New York and the other actually participated in the study. He has an author credit on the newly published study in the journal Nature Communication.

“We actually broke the wall between private collectors and scientists which is very uncommon, especially in paleontology,” Pérez-de la Fuente says. “That by itself is a success.”

May it be the first of many.