The British Museum and the Google Arts & Culture have been collaborating on creating a complex, in depth digital virtual museum experience for years now. It’s been an exceptionally fruitful partnership from the outset, when the the new Google subsite dedicated to the British Museum’s physical structure, contents, permanent collection and exhibitions opened two years ago. Google Street View’s cameras crawled the entire space and put one of the world’s greatest encyclopedic museums online for everyone in the world with an Internet connection to explore in mind-blowing detail. The collection was rephotographed, this time in the massive resolution of gigapixel cameras, so objects could be viewed on computer screens in far greater dimensions than in person.

The British Museum and the Google Arts & Culture have been collaborating on creating a complex, in depth digital virtual museum experience for years now. It’s been an exceptionally fruitful partnership from the outset, when the the new Google subsite dedicated to the British Museum’s physical structure, contents, permanent collection and exhibitions opened two years ago. Google Street View’s cameras crawled the entire space and put one of the world’s greatest encyclopedic museums online for everyone in the world with an Internet connection to explore in mind-blowing detail. The collection was rephotographed, this time in the massive resolution of gigapixel cameras, so objects could be viewed on computer screens in far greater dimensions than in person.

Their latest endeavour is dedicated to the preservation of endangered Mayan cultural knowledge and artifacts. It’s a fully functional guided tour, not just of the British Museum’s Maya collection, but of Mayan history and culture. If you go through the virtual exhibition in order, you’ll first encounter an introduction by writer Kanishk Tharoor who gives a summary of who the Maya were and are, a timeline of key events, what we know about their cities, architecture, engineering, language, art and science. That’s followed by a piece by historian Robert Bevan on what the collapse of Mayan cities can tell us about our own present. It’s highly relevant to the British Museum’s collection because since the Spanish burned almost all of the written manuscripts, in order to read Mayan history we have to rely on inscriptions carved in stone.

Their latest endeavour is dedicated to the preservation of endangered Mayan cultural knowledge and artifacts. It’s a fully functional guided tour, not just of the British Museum’s Maya collection, but of Mayan history and culture. If you go through the virtual exhibition in order, you’ll first encounter an introduction by writer Kanishk Tharoor who gives a summary of who the Maya were and are, a timeline of key events, what we know about their cities, architecture, engineering, language, art and science. That’s followed by a piece by historian Robert Bevan on what the collapse of Mayan cities can tell us about our own present. It’s highly relevant to the British Museum’s collection because since the Spanish burned almost all of the written manuscripts, in order to read Mayan history we have to rely on inscriptions carved in stone.

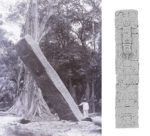

Atmospheric erosion has caused many in situ written carvings to become illegible, but a new collaboration between Google Arts & Culture and the British Museum is working to combat this gradual destruction. Using 19th century photographs and casts, combined with 21st century digital techniques, means fresh texts to decipher, and a deeper understanding of the ancient Maya.

The project’s source material is the work of the much-overlooked Victorian explorer Alfred Maudslay who traveled through Guatemala, Mexico and Honduras in the 1880s. He used the up-to-date photographic technique of dry plate photography and hauled tons of plaster of Paris with him to create moulds of some of the monuments he encountered, and paper to make impressions (‘squeezes’) of others. 400 of the resulting casts and 800 glass plate negatives are now in the British Museum, among the 100,000 American items held in its collection.

Now, all of these casts and squeezes are being 3D-scanned, allowing researchers to manipulate the images in a way that will assist in translating the Maya inscriptions. Alongside this, an immersive VR journey is being created that takes children, via objects in the museum, to see the ruins in the forests of the Maya region, complete with howler monkeys and soaring ceiba trees that, amongst the Maya, are thought to connect the underworld with the sky. The project is giving us a clearer picture of what happened to the ancient Maya.

Bevan’s article includes embeds of some of the newly digitized Mauslay photographs and 3D models of the moulds he took. You cannot download them, sad to say, but click on the embeds to see them in their fully zoomable fulgor. The next section is a multi-media slide show that explain Mayan writing, the conservation of Mauslay’s casts, the history of Guatemalan masks and the many challenges of preserving Mayan monuments using pictures and animated street view captures. It culminates in a YouTube video of curator Dr. Jago Cooper speaking about Maudslay’s work and how the British Museum can help Google to preserve Mayan history.

Bevan’s article includes embeds of some of the newly digitized Mauslay photographs and 3D models of the moulds he took. You cannot download them, sad to say, but click on the embeds to see them in their fully zoomable fulgor. The next section is a multi-media slide show that explain Mayan writing, the conservation of Mauslay’s casts, the history of Guatemalan masks and the many challenges of preserving Mayan monuments using pictures and animated street view captures. It culminates in a YouTube video of curator Dr. Jago Cooper speaking about Maudslay’s work and how the British Museum can help Google to preserve Mayan history.

The next section is another slideshow, this one about the history of the museum’s Mayan collection which is of comparatively recent extraction. They didn’t really start collecting Maya artifacts until the mid-19th century. Maudslay’s casts didn’t join the party until the 1920s and the best known original artifacts only arrived in the 1930s when coffee planter Charles Fenton donated his important private collection to the museum. The two slideshows after this one focus on the explorer and his casts, followed by a huge photos and 3D models of the casts.

The next section is another slideshow, this one about the history of the museum’s Mayan collection which is of comparatively recent extraction. They didn’t really start collecting Maya artifacts until the mid-19th century. Maudslay’s casts didn’t join the party until the 1920s and the best known original artifacts only arrived in the 1930s when coffee planter Charles Fenton donated his important private collection to the museum. The two slideshows after this one focus on the explorer and his casts, followed by a huge photos and 3D models of the casts.

Because it’s Google we’re talking about, there are opportunities to take a virtual stroll through ancient Maya archaeological sites, explore their cities in 360-degree flexibility, even tools for teachers to design virtual trips through space and time for their classes. It’s an ambitious assemblage with a deep bench of content and media to devour. So what are you waiting for?

Because it’s Google we’re talking about, there are opportunities to take a virtual stroll through ancient Maya archaeological sites, explore their cities in 360-degree flexibility, even tools for teachers to design virtual trips through space and time for their classes. It’s an ambitious assemblage with a deep bench of content and media to devour. So what are you waiting for?