Groundbreaking analysis of ancient DNA has answered a century-old question: are a pair of Egyptian mummies from the 12th Dynasty dubbed the Two Brothers actually brothers? One hundred and eleven years after their discovery, we now know the answer is yes. They are half-brothers, same mother, different fathers. This overturns the results from the original 1908 study that indicated no familial relationship between the two men.

Groundbreaking analysis of ancient DNA has answered a century-old question: are a pair of Egyptian mummies from the 12th Dynasty dubbed the Two Brothers actually brothers? One hundred and eleven years after their discovery, we now know the answer is yes. They are half-brothers, same mother, different fathers. This overturns the results from the original 1908 study that indicated no familial relationship between the two men.

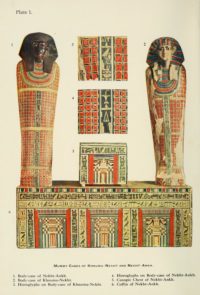

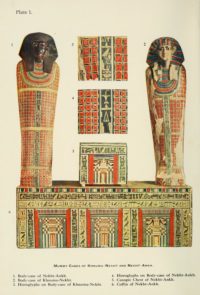

The mummies of Khnum-nakht and Nakht-ankh were discovered by renown archaeologist Flinders Petrie in a stone-cut tomb near the village of Deir Rifeh in 1907. Their exquisitely painted coffins were placed next to each other and inscriptions on their sarcophagi identified them as brothers, sons of a local governor (an unnamed “hatia-prince”) and a woman (or women) named Khnum-aa. The richness of the funerary furnishings in the tomb confirmed their high status as the sons of an elite functionary. The style of the tomb dated it to around 1,800 B.C.

Flinders Petrie wrote to the Manchester Museum that his team had discovered a small 12th Dynasty tomb in Rifeh packed tightly with two polychrome painted sarcophagi complete with mummies, two funerary boats with servant figurines, a painted chest with a full set of four canopic jars, five statuettes placed in the coffins and two pottery vessels. All the human remains were intact and the craftsmanship of the artifacts of the highest quality. Petrie, keen to ensure the core funerary group would stay together, offered it to the museum for a £500 contribution to his next excavation. The Museum Committee accepted with alacrity and raised £570 19s in a few weeks thanks to the donations of boosters. The extra £70 19s went to the writing and production of a The Tomb of Two Brothers, a publication about the museum’s research into the find.

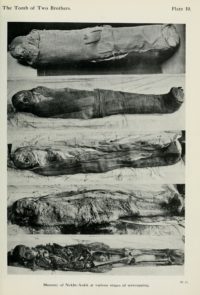

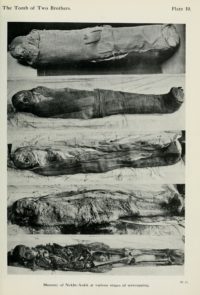

This pamphlet makes fascinating reading, touching on the transition from archaeology as an amateur treasure hunt to archaeology as a science, the complicity of antiquities collectors in systemic looting of tombs, and how the sausage of the examination of the remains was made in the Edwardian era. Hint: it ain’t pretty. Cringeworthy in an age when mummies are never unwrapped precisely because of the damage described in the publication: soft tissues disappearing into clouds of dust and moisture causing long-preserved flesh to rapidly decay.

This pamphlet makes fascinating reading, touching on the transition from archaeology as an amateur treasure hunt to archaeology as a science, the complicity of antiquities collectors in systemic looting of tombs, and how the sausage of the examination of the remains was made in the Edwardian era. Hint: it ain’t pretty. Cringeworthy in an age when mummies are never unwrapped precisely because of the damage described in the publication: soft tissues disappearing into clouds of dust and moisture causing long-preserved flesh to rapidly decay.

It’s of particular interest in the light of the recent DNA analysis that upends the conclusion drawn from the initial study. The introduction opens with a broadside to those who would castigate archaeologists as desecrators of the dead, pointing the finger back at accusers who “would not hesitate to wear a scarab-ring taken off a dead man’s hand” and who “will handle without a qualm the amulets that were found actually inside a body.” This hypocrisy, the authors note, has real consequences on the treatment of human remains because it creates a market for looters to tear apart dead bodies for saleable trinkets.

They go on to explain why the examination of dead bodies is important.

Archaeology has been raised to the rank of a science within one generation: before that it was merely the pastime of the dilettante and the amateur who amused himself by adding beautiful specimens to his collection of ancient art. Then came the period of the enthusiast in languages, to whom inscriptions the joy of life. And now there has arisen a new school to whom archaeology is a science, a science which embraces the whole field of human activity. Archaeology, in other words, is the history of the human race. It is a science which contains within itself all other sciences. The new sciences of psychology and comparative religion owe their being to archaeology, and history itself is merely archaeology in a narrow form.

Four sciences are listed as examples of disciplines that rely on information derived from material culture of the past: psychology, comparative religion, ethnology and comparative anatomy.

Archaeology can assist these four great sciences only by opening and examining graves and their contents. It is only by a knowledge of the objects placed with the dead, and by the methods of burial, that we the ideas of early races as to a future life; by studying these graves in chronological order we trace the growth of ideas and the evolution of religion and of the philosophy of life. By an examination of the bodies, the knowledge of the ethnologist and the anatomist is immensely increased.

It’s an interesting juxtaposition, the fervent belief that their morphological analyses form the scientific backbone of numerous academic disciplines vs. the DNA testing that proved the inaccuracy of said analyses. One of the sciences listed, ethnology, which at the time was emphatically focused on the putative anatomical differences between races and genders of humans, appears to have been the grounding for the erroneous conclusion.

Led by Dr. Margaret Murray, archaeological pioneer and the UK’s first woman Egyptologist, the Manchester Museum team examined the mummified remains in 1908. The team’s anatomist, Dr. John Cameron, compared their skulls and declare the differences between them “so pronounced that it is almost impossible to convince oneself that they belong to the same race, far less to the same family.” He thought the older brother, Nakht-ankh, might be a woman because the evidence of muscular attachment was so faint. When the pelvis established he was male despite the “female character” of the skull, Cameron looked for another explanation:

Led by Dr. Margaret Murray, archaeological pioneer and the UK’s first woman Egyptologist, the Manchester Museum team examined the mummified remains in 1908. The team’s anatomist, Dr. John Cameron, compared their skulls and declare the differences between them “so pronounced that it is almost impossible to convince oneself that they belong to the same race, far less to the same family.” He thought the older brother, Nakht-ankh, might be a woman because the evidence of muscular attachment was so faint. When the pelvis established he was male despite the “female character” of the skull, Cameron looked for another explanation:

The question of the skeleton being that of a eunuch next suggested itself; but unfortunately, the state of preservation of the external genitals (see page 44) does not permit one to make a definitive pronouncement on this question. If this could have been proved definitely then we should have been provided with a distinctly rare opportunity of comparing the skeletons of two brothers, one of whom was virile, and the other a eunuch.

(Page 44 is where an extensive discussion of the man’s mummified penis and missing scrotum begins. There was no evidence of the scrotum having been surgically removed, btw.)

The virile brother has sub-Saharan African ancestry, Cameron concludes, but not exclusively. He was biracial, according to the skull feature studies prevalent at the time. Between that and the eunuch thing, the anatomist cannot accept that they are brothers, but he does explore later on the chapter the possibility that they could be half-brothers with the same mother. Their mother is titled Nebt Per, (“Lady of a House”) in the inscription, which means she had inherited an estate. A moneyed, propertied woman could easily have had children from two different husbands during a lifetime. Alternatively, one or both of them may have been adopted.

The virile brother has sub-Saharan African ancestry, Cameron concludes, but not exclusively. He was biracial, according to the skull feature studies prevalent at the time. Between that and the eunuch thing, the anatomist cannot accept that they are brothers, but he does explore later on the chapter the possibility that they could be half-brothers with the same mother. Their mother is titled Nebt Per, (“Lady of a House”) in the inscription, which means she had inherited an estate. A moneyed, propertied woman could easily have had children from two different husbands during a lifetime. Alternatively, one or both of them may have been adopted.

Either way, they were still brothers, as the contemporary inscription emphasized, and the exquisitely painted sarcophagi became the museum’s most famous icons. They have been on display almost continuously since 1908 and have been known as the Two Brothers just as long, blood relations or no. There have been multiple attempts to extract a viable DNA sample to determine the brothers’ brotherness but all of the results were inconclusive. The technology has improved greatly in recent years, however, so in 2015 scientists tried again.

[T]he DNA was extracted from the teeth and, following hybridization capture of the mitochondrial and Y chromosome fractions, sequenced by a next generation method. Analysis showed that both Nakht-Ankh and Khnum-Nakht belonged to mitochondrial haplotype M1a1, suggesting a maternal relationship. The Y chromosome sequences were less complete but showed variations between the two mummies, indicating that Nakht-Ankh and Khnum-Nakht had different fathers, and were thus very likely to have been half-brothers.

Dr Konstantina Drosou, of the School of Earth and Environmental Sciences at the University of Manchester who conducted the DNA sequencing, said: “It was a long and exhausting journey to the results but we are finally here. I am very grateful we were able to add a small but very important piece to the big history puzzle and I am sure the brothers would be very proud of us. These moments are what make us believe in ancient DNA.”

The study, which is being published in the Journal of Archaeological Science, is the first to successfully use the typing of both mitochondrial and Y chromosomal DNA in Egyptian mummies.

The new study is available online free of charge so you can read the original publication and the latest one for a one-shot comparative history of science. To paraphrase Martin Luther King, Jr. who in turn was paraphrasing Transcendentalist and Unitarian minister Theodore Parker, the arc of the scientific method is long, but it bends towards accuracy.

The original manuscript of the Marquis de Sade’s The 120 Days of Sodom has been declared national treasure by the French government. You might recall that over two years ago I wrote about how the thin (5 inches), very long (39 feet) parchment scroll on which the Marquis de Sade wrote what he considered his masterpiece was going up for auction. The circumstances were shady, to put it mildly. Quick summary: the scroll had been stolen in the early 1980s from the legitimate owner, Natalie de Noailles, daughter of a viscount and descendant of de Sade’s on her mother’s side and was sold in Switzerland (surprising no one) to an erotica collector. Noailles sued in French court, won, and the judgment was simply ignored by the Swiss collector.

The original manuscript of the Marquis de Sade’s The 120 Days of Sodom has been declared national treasure by the French government. You might recall that over two years ago I wrote about how the thin (5 inches), very long (39 feet) parchment scroll on which the Marquis de Sade wrote what he considered his masterpiece was going up for auction. The circumstances were shady, to put it mildly. Quick summary: the scroll had been stolen in the early 1980s from the legitimate owner, Natalie de Noailles, daughter of a viscount and descendant of de Sade’s on her mother’s side and was sold in Switzerland (surprising no one) to an erotica collector. Noailles sued in French court, won, and the judgment was simply ignored by the Swiss collector.  After his death, his heirs sold the parchment with the blessing of a ridiculous and offensive Swiss federal court judgment contradicting the French one. In 2014, the manuscript was sold to avid collector Gérard Lhéritier, founder of Aristophil which turned out to be not so much as a company as a Ponzi scheme that used the collection of important manuscripts and autographs to defraud people of their money. When Lhéritier and his operators were arrested in March of 2015, the collection was confiscated. Now there would be a new court ruling, and this one wasn’t so easy to ignore. The entire collection of hundreds of thousands of historic manuscripts was to be sold at auction with the profits split among creditors.

After his death, his heirs sold the parchment with the blessing of a ridiculous and offensive Swiss federal court judgment contradicting the French one. In 2014, the manuscript was sold to avid collector Gérard Lhéritier, founder of Aristophil which turned out to be not so much as a company as a Ponzi scheme that used the collection of important manuscripts and autographs to defraud people of their money. When Lhéritier and his operators were arrested in March of 2015, the collection was confiscated. Now there would be a new court ruling, and this one wasn’t so easy to ignore. The entire collection of hundreds of thousands of historic manuscripts was to be sold at auction with the profits split among creditors. Meanwhile, the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, which before the sale to Lhéritier had negotiated a complicated deal to acquire the manuscript on terms the sellers, the Noailles family and the French legal system could live with only to have it fall through at the last minute, was working another angle. If they could get the scroll declared national treasure, then its sale would be impeded.

Meanwhile, the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, which before the sale to Lhéritier had negotiated a complicated deal to acquire the manuscript on terms the sellers, the Noailles family and the French legal system could live with only to have it fall through at the last minute, was working another angle. If they could get the scroll declared national treasure, then its sale would be impeded. The scroll is undeniable an icon of French literature and a microcosm of political and moral controversies of the ancien regime, French Revolution and early Napoleonic era. The Marquis de Sade wrote it from scraps of parchment attached together to form a long, skinny scroll that looks more than a little toilet papery (very thematically appropriate considering the subjects he explores in the tome) while he was imprisoned in the Bastille. He didn’t quite make it to liberation on July 14th, 1789. Ten days before it was stormed, he was transferred from his rather nicely appointed prison cell to the Charenton insane asylum without warning or opportunity to collect his stuff in punishment for riling up the Revolutionary mob milling around outside by hollering “They’re killing prisoners in here!”

The scroll is undeniable an icon of French literature and a microcosm of political and moral controversies of the ancien regime, French Revolution and early Napoleonic era. The Marquis de Sade wrote it from scraps of parchment attached together to form a long, skinny scroll that looks more than a little toilet papery (very thematically appropriate considering the subjects he explores in the tome) while he was imprisoned in the Bastille. He didn’t quite make it to liberation on July 14th, 1789. Ten days before it was stormed, he was transferred from his rather nicely appointed prison cell to the Charenton insane asylum without warning or opportunity to collect his stuff in punishment for riling up the Revolutionary mob milling around outside by hollering “They’re killing prisoners in here!”