Ötzi the Iceman has competition for the world’s oldest tattoos from two pre-dynastic Egyptian mummies in the British Museum. Gebelein Man A and Gebelein Woman are two of six mummies unearthed in 1896 by British Museum Egyptologist Wallis Budge from their shallow sandy graves near modern-day Naga el-Gherira in southern Egypt. Covered in warm desert sand at the time of their burial, the six natural mummies were very well-preserved and the first complete predynastic bodies ever found. They were acquired by the British Museum in 1900.

Ötzi the Iceman has competition for the world’s oldest tattoos from two pre-dynastic Egyptian mummies in the British Museum. Gebelein Man A and Gebelein Woman are two of six mummies unearthed in 1896 by British Museum Egyptologist Wallis Budge from their shallow sandy graves near modern-day Naga el-Gherira in southern Egypt. Covered in warm desert sand at the time of their burial, the six natural mummies were very well-preserved and the first complete predynastic bodies ever found. They were acquired by the British Museum in 1900.

They’ve been on display for more than a century, but nobody realized Gebelein Man A and Gebelein Woman had tattoos until a recent infrared examination. All that’s visible to the naked eye on Gebelein Man is a faint smudge on his upper right arm. Infrared photography revealed the smudge is actually a tattoo, and a figural one at that. It depicts two horned animals, one with a long tail and elaborate horns identifying it as a wild bull, the other with the curving horns and a shoulder hump characteristic of a Barbary sheep. The iconographic references are recognizable because they come up regularly in the art of Predynastic Egypt. This is just the first time they’ve come up in body art. The animal figures are thought to symbolize strength, still today an immensely popular motif in tattoo art.

They’ve been on display for more than a century, but nobody realized Gebelein Man A and Gebelein Woman had tattoos until a recent infrared examination. All that’s visible to the naked eye on Gebelein Man is a faint smudge on his upper right arm. Infrared photography revealed the smudge is actually a tattoo, and a figural one at that. It depicts two horned animals, one with a long tail and elaborate horns identifying it as a wild bull, the other with the curving horns and a shoulder hump characteristic of a Barbary sheep. The iconographic references are recognizable because they come up regularly in the art of Predynastic Egypt. This is just the first time they’ve come up in body art. The animal figures are thought to symbolize strength, still today an immensely popular motif in tattoo art.

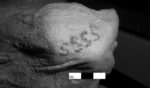

Gebelein Woman’s tattoos at first glance do not appear to be figural. IR revealed the presence of four S-shaped figures running over her right shoulder and a bent line a little further down her right arm. Again, both of these motifs are found on predynastic painted pottery. However, the linear piece may not be an abstract design. It is similar to objects held in the hands of figures believed to be participating in religious rituals. Researchers think they may be clappers used in ceremonial dance. It could also be a staff symbolizing her holding high office. It’s possible they and the s shapes served a spiritual function on her body as well, marking her as a woman of status, advanced cult knowledge or singling her out for protection.

Gebelein Woman’s tattoos at first glance do not appear to be figural. IR revealed the presence of four S-shaped figures running over her right shoulder and a bent line a little further down her right arm. Again, both of these motifs are found on predynastic painted pottery. However, the linear piece may not be an abstract design. It is similar to objects held in the hands of figures believed to be participating in religious rituals. Researchers think they may be clappers used in ceremonial dance. It could also be a staff symbolizing her holding high office. It’s possible they and the s shapes served a spiritual function on her body as well, marking her as a woman of status, advanced cult knowledge or singling her out for protection.

Dating to between 3351 and 3017 B.C. (Ötzi died around 5,300 years ago, so the Iceman and the sand people are roughly the same age when accounting for margins of error), the Gebelein mummies can each claim new records in the history of tattooing. Gebelein Man has the earliest figural art; Gebelein Woman is the oldest known tattooed woman in the world. Ötzi’s tattoos are patterns of dots and lines.

Dating to between 3351 and 3017 B.C. (Ötzi died around 5,300 years ago, so the Iceman and the sand people are roughly the same age when accounting for margins of error), the Gebelein mummies can each claim new records in the history of tattooing. Gebelein Man has the earliest figural art; Gebelein Woman is the oldest known tattooed woman in the world. Ötzi’s tattoos are patterns of dots and lines.

The results of the study have been published in the latest issue of the Journal of Archaeological Science, but the issue is in progress and the article is not yet available online.

Daniel Antoine, one of the lead authors of the research paper and the British Museum’s Curator of Physical Anthropology said:

“The use of the latest scientific methods, including CT scanning, radiocarbon dating and infrared imaging, has transformed our understanding of the Gebelein mummies. Only now are we gaining new insights into the lives of these remarkably preserved individuals. Incredibly, at over five thousand years of age, they push back the evidence for tattooing in Africa by a millennium.”