The Metropolitan Museum of Art contains many marvels of history and art. The Adeline Harris Sears Tumbling Block with Signatures quilt stands up to any of them for its uniqueness, artistry and unparalleled capture of the history and society of mid-19th century America. Quilts incorporating signatures weren’t new when the teenaged Adeline began her project in 1856, but they were community works, the product of families and churches working together to create a piece for an event like a wedding or baptism. The Met has a lovely example of that type of quilt: an Album quilt by members of the Brown and Turner families of Baltimore, begun in 1846. Adeline’ quilt is something else entirely.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art contains many marvels of history and art. The Adeline Harris Sears Tumbling Block with Signatures quilt stands up to any of them for its uniqueness, artistry and unparalleled capture of the history and society of mid-19th century America. Quilts incorporating signatures weren’t new when the teenaged Adeline began her project in 1856, but they were community works, the product of families and churches working together to create a piece for an event like a wedding or baptism. The Met has a lovely example of that type of quilt: an Album quilt by members of the Brown and Turner families of Baltimore, begun in 1846. Adeline’ quilt is something else entirely.

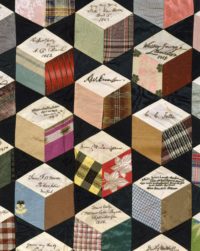

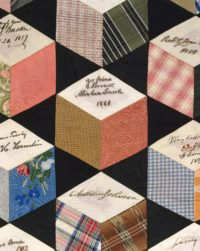

The signatures include congressmen (including Elihu Washburne of Illinois, John Sherman of Ohio), senators (including Solomon Foot of Vermont, Charles Sumner of Massachusetts and William H. Seward of New York, later Lincoln’s Secretary of State), governors (including Sam Houston of Texas, William Buckingham of Connecticut) Union Army generals (including Ambrose Burnside, George McClellan, Joseph Hooker and George Meade, victor of Gettysburg), an astonishing eight presidents of the United States (Martin Van Buren, John Tyler, Millard Fillmore, Franklin Pierce, James Buchanan, Abraham Lincoln, Andrew Johnson, Ulysses S. Grant) and two vice presidents (Schuyler Colfax and Henry Wilson).

There are also notable academics, university presidents, journalists and editors, actors, reformers, scientists, artists, poets, essayists, novelists, folklorists, clergymen from numerous denominantions. Rubbing shoulders on this extraordinary quilt are the autographs of Samuel Morse, Horace Greeley, Washington Irving, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Julia Ward Howe, Harriet Beecher Stowe, William Cullen Bryant, Alexandre Dumas, Oliver Wendell Holmes, William Makepeace Thackeray and Charles Dickens.

There are also notable academics, university presidents, journalists and editors, actors, reformers, scientists, artists, poets, essayists, novelists, folklorists, clergymen from numerous denominantions. Rubbing shoulders on this extraordinary quilt are the autographs of Samuel Morse, Horace Greeley, Washington Irving, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Julia Ward Howe, Harriet Beecher Stowe, William Cullen Bryant, Alexandre Dumas, Oliver Wendell Holmes, William Makepeace Thackeray and Charles Dickens.

And that’s just scratching the surface. Adeline assembled a who’s who of 19th century society for her quilt, the majority of which are still very much luminaries of their fields, even when, as in the case of most of the clergymen, they are not as well known as they were in their lifetimes.

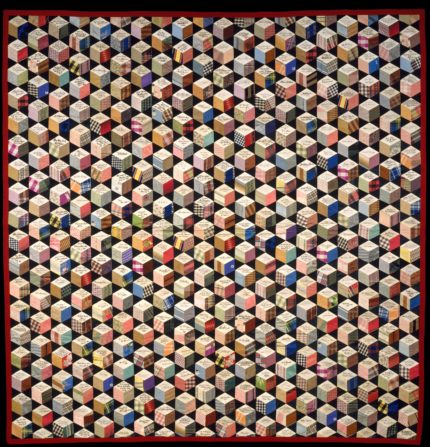

The tumbling blocks pattern is characterized by a trompe l’oeil that gives it a 3D cube effect. Adeline Harris showcased exceptional skill and mastery in her needlework and fabric choice, emphasizing the 3D effect with her arrangement of the varied patterns of silk pieces. The white pieces with autographs all serve as the top of the cubes, while the two visible sides, corner center, are formed by contrasting silk panels. To these she sewed black silk triangles, thereby creating a deep, velvety background to make the cubes pop.

There are 360 blocks with signatures and 10 signatureless partial blocks in the top border, arranged in 20 columns and 36 rows (plus a half row up top). Adeline first put together the blocks, then stitched them together as columns, then stitched the columns together to form the rows. There are 1,840 pieces of silk of 150 different patterns and colors in the entire quilt, most of them imported from Europe and first used in clothing, hats and ribbons before being reincarnated in the quilt. Even the black triangles are diverse, with five different kinds of silks used to create the background.

Adeline’s stitching is the peak of quilt craftsmanship. Look at how sharp and regular the blocks are, how flawlessly they are sewed together so all the corners meet. Then there’s the condition of the fabrics themselves. These scraps were lovingly preserved for who knows how long, and then the quilt itself was preserved in pristine condition by the family for another 140 years. The colors are still brilliant with only minimal fading on the more delicate pink shades.

The quilt also showcases its maker’s logical mind, mathematical precision and thorough engagement in the politics and literature of her time. She was the daughter of a prosperous Rhode Island textile mill owner and had received what was considered a proper education for a girl of her class (mostly from private tutors in her home, plus three years at private boarding schools). Her granddaughter described her as “a great scholar and student with a brilliant mind” and the quilt certainly doesn’t contradict that glowing report. She placed the autographs in categories — presidents and vice presidents in column seven, generals in columns two and three, authors arranged first by gender, then by prominence, then by genre, etc. It’s like a giant matrix of 19th century celebrities.

The quilt also showcases its maker’s logical mind, mathematical precision and thorough engagement in the politics and literature of her time. She was the daughter of a prosperous Rhode Island textile mill owner and had received what was considered a proper education for a girl of her class (mostly from private tutors in her home, plus three years at private boarding schools). Her granddaughter described her as “a great scholar and student with a brilliant mind” and the quilt certainly doesn’t contradict that glowing report. She placed the autographs in categories — presidents and vice presidents in column seven, generals in columns two and three, authors arranged first by gender, then by prominence, then by genre, etc. It’s like a giant matrix of 19th century celebrities.

The quilt is also a testament to her persistence, stamina and focus. It took her 11 years to collect all of the autographs (1856-1867), and even more years to stitch them together. This is evidenced by her placement of President Grant who was not president when he signed her silk diamond and his vice presidents Colfax and Wilson who signed theirs in the late 1850s long before they reached their highest offices. That means she worked on this quilt for nigh on two decades.

One of the personages Adeline wrote to soliciting her autograph was Sarah J. Hale, editor of Godey’s Lady’s Book. She explained her project in a letter that so impressed Hale that she wrote a two-part article about the quilt, describing its ambitious reach and design and complimenting its creator for her ingenunity and needlework abilities. Hale saw this quilt as both “intellectual” and “moral” endeavour, as it required brain power and taste to piece together the riot of color and pattern into a matched and pleasing geometry, and a virtuous understanding of “the fitness of things” to pick celebrities whose deeds and talents would make them worthy of being cast in this silken firmament.

One of the personages Adeline wrote to soliciting her autograph was Sarah J. Hale, editor of Godey’s Lady’s Book. She explained her project in a letter that so impressed Hale that she wrote a two-part article about the quilt, describing its ambitious reach and design and complimenting its creator for her ingenunity and needlework abilities. Hale saw this quilt as both “intellectual” and “moral” endeavour, as it required brain power and taste to piece together the riot of color and pattern into a matched and pleasing geometry, and a virtuous understanding of “the fitness of things” to pick celebrities whose deeds and talents would make them worthy of being cast in this silken firmament.

In the April 1864 issue of Godey’s Lady Book, Hale wrote in “Autograph Bedquilt”, the first part of the article:

Notwithstanding the comprehensive design we are attempting to describe, we have no doubt of its successful termination. The letter of the young lady bears such internal evidence of her capability, that we feel certain she has the power to complete her work if her life is spared. And when we say that she has been nearly eight years engaged on this quilt, and seems to feel now all the enthusiasm of a poetical temperament working out a grand invention that is to be a new pleasure and blessing to the world, we are sure all our readers will wish her success. Who knows but in future ages, her work may be looked at like the Bayeux Tapestry, not only as a marvel of woman’s ingenious and intellectual industry; but as affording an idea of the civilization of our times, and giving a notion of the persons as estimated in history.

You called it, Ms. Hale.

Adeline’s daughter Sophie and her daughters in turn recognized what a masterpiece their mother and grandmother had created. It does not appear to have been used as a bedspread, but rather was treasured and preserved most careful. There is evidence that it was hung for display at some point.

Even so, close examination of the back of the quilt found an amusing interlude of censorship in its history. The last diamond was covered up at some point by a patch. The needle holes are still visible even though the patch had been removed by the time the Met acquired the quilt. Apparently the poem written on that piece, thought to be by Nathaniel P. Willis whose signature appears in column 18, caused some pearls to be clutched resulting in the application of a quilted fig leaf which thankfully did not endure. I hope your blushing eyes can handle it.

Miss Addie pray excuse

My disobliging Muse,

She contemplates with dread

So many in a Bed.

EDIT: I considered including a full list of the signatures in this post, but it is very long and my only source is a pdf of a 1998 journal article from the Met so formatting it for posting is a bit of a nightmare. Instead, I’m attaching the article with the appendix that lists all the signatures, complete with greetings and brief biographical line identifying the signers, by column. The appendix begins on page 277 (page 15 of the pdf). (But read the whole article because it’s awesome.)

“A Marvel of Woman’s Ingenious and Intellectual Industry”: The Adeline Harris Sears Autograph Quilt, by Amelia Peck, Associate Curator, American Decorative Arts, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Metropolitan Museum Journal issue 33, 1998.