Researchers have found traces of ancient opium in a Bronze Age vessel, the first chemical confirmation that a type of pottery jug long suspected to have been used to hold opiates were indeed used for that purpose.

Researchers have found traces of ancient opium in a Bronze Age vessel, the first chemical confirmation that a type of pottery jug long suspected to have been used to hold opiates were indeed used for that purpose.

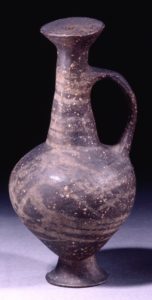

The vessel in question is a base-ring juglet now in the collection of the British Museum. It was made in Cyprus during the Late Bronze Age period classified as Late Cypriot II (1450-1200 B.C.). This was a period of great prosperity in the Mediterranean, with flourishing trade and prosperity leading to a rise in urban development and the introduction of literacy in the form of a variant of Minoan Linear A.

The juglet has an ovoid body on a ring base with a long, narrow neck. It is made of high-quality clay fired black and then painted with white bands on the body and neck. The shape looks like an opium poppy head turned upside down, and scholars have hypothesized that this is not a coincidence or a mere artistic inspiration, but a deliberate choice to match the design of the container to the substance it was designed to contain.

Past attempts to analyze the residue in base-ring juglets for chemical proof of the presence of the opium poppy were unsuccessful. This particular example gave researchers the unique opportunity to pursue that hypothesis because it is intact with its original seal in place. British Museum scientists found that the residue inside the juglet was primarily composed of plant oil that suggested the presence of opium alkaloids. That suggestion was insufficient to confirm that the vessel had contained opium poppy derivatives. University of York chemists devised a new analytical approach to confirm the presence of those tell-tale alkaloids in the plant oil.

Past attempts to analyze the residue in base-ring juglets for chemical proof of the presence of the opium poppy were unsuccessful. This particular example gave researchers the unique opportunity to pursue that hypothesis because it is intact with its original seal in place. British Museum scientists found that the residue inside the juglet was primarily composed of plant oil that suggested the presence of opium alkaloids. That suggestion was insufficient to confirm that the vessel had contained opium poppy derivatives. University of York chemists devised a new analytical approach to confirm the presence of those tell-tale alkaloids in the plant oil.

Using instruments in the Centre of Excellence in Mass Spectrometry at the University of York, Dr Rachel Smith developed the new analytical method as part of her PhD at the University’s Department of Chemistry.

Dr Smith said: “The particular opiate alkaloids we detected are ones we have shown to be the most resistant to degradation, which makes them better targets in ancient residues than more well-known opiates such as morphine.

“We found the alkaloids in degraded plant oil, so the question as to how opium would have been used in this juglet still remains. Could it have been one ingredient amongst others in an oil-based mixture, or could the juglet have been re-used for oil after the opium or something else entirely?”

The opiate residue does not mean opiates were traded as lotus eater-style mind-altering substances. If the opium poppy was indeed an ingredient in an oil preparation, it could have been a perfume or used for ritual anointing. Opium has been prized since antiquity for its medicinal properties, so it might have been a pharmacological preparation.

Professor Jane Thomas-Oates, Chair of Analytical Science in the Department of Chemistry, and supervisor of the study at the University of York, said: “The juglet is significant in revealing important details about trade and the culture of the period, so it was important to us to try and progress the debate about what it might have been used for.

“We were able to establish a rigorous method for detecting opiates in this kind of residue, but the next analytical challenge is to see if we can succeed with less well-preserved residues.”