In 2011, construction work on Corona Avenue in Queens accidentally (and roughly) unearthed the remains of a woman. The backhoe had wrenched open the coffin, dragged the body out and covered it with piles of soil, but still the remains were so well-preserved that at first it was investigated as a potential crime victim. Scott Warnasch, forensic archaeologist with the New York City Office of Chief Medical Examiner, identified it as a historical burial from fragments of iron he recovered at the site, pieces of the damaged coffin of a type that was made in the mid-18th century.

In 2011, construction work on Corona Avenue in Queens accidentally (and roughly) unearthed the remains of a woman. The backhoe had wrenched open the coffin, dragged the body out and covered it with piles of soil, but still the remains were so well-preserved that at first it was investigated as a potential crime victim. Scott Warnasch, forensic archaeologist with the New York City Office of Chief Medical Examiner, identified it as a historical burial from fragments of iron he recovered at the site, pieces of the damaged coffin of a type that was made in the mid-18th century.

A visual examination of the mummified remains determined that they belonged to an adult African-American woman. She was clad in a loose-fitting garment recognizable as a 19th century nightdress, knee-high socks and a knit cap. Her skin was largely intact and in so free of decomposition that smallpox lesions could clearly be seen on her head, chest, legs, even feet. Experts from the CDC were called in to ensure there were no infectious pathogens still active in the remains.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed X-ray tomography (CT) scans allowed the scientists to examine the body noninvasively and create a biological profile of the woman: They determined she was 5 feet, 2 inches tall (1.6 meters), African-American and about 25 to 30 years old, Warnasch explained.

The site where she was discovered was formerly an African-American church and cemetery; the church was founded in 1828 by the region’s first generation of free black people, but there are newspaper accounts of an African-American cemetery on that land dating to a decade earlier, according to Warnasch.

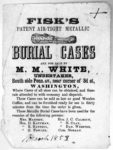

An expensive iron coffin was an unexpected final resting vessel for a young African-American woman from Newtown (modern-day Elmhurst), Queens, which was then a small farming town. First patented by Almond Dunbar Fisk in 1848, the cast iron coffins quickly became very desirable items for the wealthy. Fisk had been inspired to invent them when his brother William died in Mississippi in 1840 and could not be transported to New York for burial in the family plot because the journey was so long. His father Solomon was devastated by this, and in response to Solomon’s heavy grief, Fisk conceived the idea for an air-tight coffin that would preserve a body for transport even over great distances. The market for such a product was wider than that. Anybody who could afford to keep a loved one out of the hands of the dreaded resurrection men would buy a Fisk coffin too. When former First Lady (the first First Lady as we think of the role today) Dolley Madison was buried in a Fisk coffin in 1849, they became immensely popular among the political and societal elite.

An expensive iron coffin was an unexpected final resting vessel for a young African-American woman from Newtown (modern-day Elmhurst), Queens, which was then a small farming town. First patented by Almond Dunbar Fisk in 1848, the cast iron coffins quickly became very desirable items for the wealthy. Fisk had been inspired to invent them when his brother William died in Mississippi in 1840 and could not be transported to New York for burial in the family plot because the journey was so long. His father Solomon was devastated by this, and in response to Solomon’s heavy grief, Fisk conceived the idea for an air-tight coffin that would preserve a body for transport even over great distances. The market for such a product was wider than that. Anybody who could afford to keep a loved one out of the hands of the dreaded resurrection men would buy a Fisk coffin too. When former First Lady (the first First Lady as we think of the role today) Dolley Madison was buried in a Fisk coffin in 1849, they became immensely popular among the political and societal elite.

In 1850, a pine coffin cost $2 in 1850. A Fisk metal coffin cost $100. This was an unaffordable price for people of modest means such as the African-American community of Newtown, all of them either the children of slaves or freed slaves. (Slavery was only fully outlawed in 1828 in the state of New York.) The woman had been lovingly prepared for burial, cleaned, dressed in a lace nightdress, a handsome comb and bonnet placed in her hair, but none of her funerary accessories indicated the kind of wealth needed to make an iron coffin even remotely possible.

Warnasch used the date the coffin was manufactured (1848-1854) and the first federal census to include free people of color by name (1850) to seek out the woman in the iron coffin’s identity. He was able to narrow it down to one very strong possibility: Martha Peterson, daughter of John and Jane Peterson, who died at the age of 26.

Warnasch used the date the coffin was manufactured (1848-1854) and the first federal census to include free people of color by name (1850) to seek out the woman in the iron coffin’s identity. He was able to narrow it down to one very strong possibility: Martha Peterson, daughter of John and Jane Peterson, who died at the age of 26.

John Peterson was the president of the United African Society, the organization which purchased the land for the cemetery. He was a prominent member of the community and had a direct link to the founding of the burial ground. That would help explain the high level of care given the body despite her death from a highly infectious air-borne disease as well as the expensive coffin.

The smallpox alone would have been sufficient reason to pay the price for a Fisk coffin because infected cadavers could still transmit the deadly disease. Burying her in an air-tight coffin would protect the close-knit community from a potential epidemic.

Forensic specialists initially thought that Peterson might have been buried in the iron coffin because her loved ones feared the spread of disease. However, further analysis led the investigators toward a different explanation, Warnasch said, adding, “but I don’t want to give too much away.”

He doesn’t want to spoil the episode of the PBS show Secrets of the Dead which covers the discovery of the body and subsequent research. I have no such scruples because revealing 150-year-old spoilers is pretty much the entire point of this blog. I’ve watched the program and I’m sure it will be just as fascinating to watch even if you know ahead of time what they’ve discovered, but in case some of you are highly sensitive to revelation of denouements in history documentaries, I’ll put the key discovery on page two.

Or you could just go right to the documentary. In addition to the interesting find Warnasch refers to, there is an amazing section about the results of the MRI and how the smallpox lesions were founds inside her brain. The full episode is available for viewing on the PBS website. Watch it now before they take it down.