Heading south in the historic center shortly before one encounters a rhino in front of a quadrifons arch, there’s a lovely palazzo off Piazza Campitelli on the Via Montanara. The first time I happened past it was when I went to the Museo della Mura at the Porta Appia. That was Sunday and the portellone (big ol’ door) was closed so it was just a felicitously located building. I barely noted it because it was clearly new (well, new for Rome).

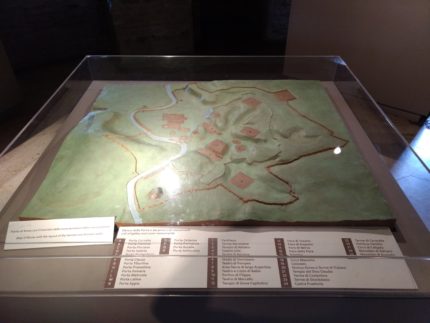

When I returned down that path for the Wednesday excursion which took me past the rhino, the portellone was wide open and I saw a beautiful courtyard with a fountain and a few handsome pieces of ancient marble work. That was notable and how. I popped in to have a quick look around, as one does in open doors in Rome, and I saw this:

When I returned down that path for the Wednesday excursion which took me past the rhino, the portellone was wide open and I saw a beautiful courtyard with a fountain and a few handsome pieces of ancient marble work. That was notable and how. I popped in to have a quick look around, as one does in open doors in Rome, and I saw this:

That is what the employees of the Municipal Department of Culture see every morning when they trudge in to the office. The door was open for randos like me to wander in because there’s a little information booth with a bunch of pamphlets about cultural activities sponsored by the city and oh yeah, a freaking incredible view of three important ancient sites and a cool Renaissance building.

The view from the courtyard stretches from the slopes of the Capitoline to the Velabrum valley. This was always a busy area, even before the Cloaca drained the marsh, because it’s where the Isola Tiberina divides the Tiber making a convenient ford for a commercial harbor. The remains of the first bridge built on the river, the Ponte Rotto, still stand in front of the island.

The view from the courtyard stretches from the slopes of the Capitoline to the Velabrum valley. This was always a busy area, even before the Cloaca drained the marsh, because it’s where the Isola Tiberina divides the Tiber making a convenient ford for a commercial harbor. The remains of the first bridge built on the river, the Ponte Rotto, still stand in front of the island.

Once the marshes were dried up, the area filled with temples and monumental structures. The Theater of Marcellus was built in by August in 13 or 11 B.C. in memory of his beloved nephew who died at a young age under suspicious circumstances (did Livia poison him?). It was originally three levels high, the first level supported by Doric columns, the second Ionic and the third adorned by Corinthian pilasters. It seated 15,000.

A Temple of Apollo was first built on the site in 431 B.C. by consul Gnaeus Iulius Mento in thanks for the conclusion of a plague. It was the first and for centuries the only temple to Apollo in the city. The remains visible today date to a rebuild of the site during the Augustan period, a rebuild made necessary by various demolitions done to accommodate the Theater of Marcellus.

You will not be surprised to hear that the theater, like sooo many other ancient Roman buildings, was converted into a fortress by local potentates. In the Renaissance the fortress got an architectural upgrade into a palace, designed by Baldassarre Peruzzi for the noble Savelli family, later owned by the Orsini.

You will not be surprised to hear that the theater, like sooo many other ancient Roman buildings, was converted into a fortress by local potentates. In the Renaissance the fortress got an architectural upgrade into a palace, designed by Baldassarre Peruzzi for the noble Savelli family, later owned by the Orsini.

In the 1930s, the Fascist thirst for creating a grandiose vision of the ancient Caput Mundi led to the demolition of much of the medieval and Renaissance construction in the area. The columns from the Temple of Apollo, incorporated into a later building, were reconstructed in their original location and raised on April 21st, 1940, Rome’s birthday. Other remains were released from the bondage of the structures built on top of them.

In the 1930s, the Fascist thirst for creating a grandiose vision of the ancient Caput Mundi led to the demolition of much of the medieval and Renaissance construction in the area. The columns from the Temple of Apollo, incorporated into a later building, were reconstructed in their original location and raised on April 21st, 1940, Rome’s birthday. Other remains were released from the bondage of the structures built on top of them.

So what you see from the courtyard is a remarkable cross-section of Roman history. The tower in the left middle ground is the Torre dei Pierleoni, a medieval defensive tower once linked to all the fortressification of the Theater of Marcellus. A block or so behind it, past the tree, is the facade of Santa Maria in Cosmedin, of Bocca della Verita’ fame. On the right is the Theater of Marcellus, only two of its original three ancient storeys remaining, with the Renaissance  palazzo taking up the third storey now. The columns and hill they’re on are the site of the Temple of Apollo. The mass against the fence in the left foreground is the podium of the Temple of Bellona, originally erected in 296 B.C. to celebrate a victory over the Etruscans and also reconstructed under Augustus (5-15 B.C.). The building with the tile roof overlooking the Temple of Apollo is the Albergo della Catena, an active inn from at least the 16th century until 1931 when it was bought by the city of Rome.

palazzo taking up the third storey now. The columns and hill they’re on are the site of the Temple of Apollo. The mass against the fence in the left foreground is the podium of the Temple of Bellona, originally erected in 296 B.C. to celebrate a victory over the Etruscans and also reconstructed under Augustus (5-15 B.C.). The building with the tile roof overlooking the Temple of Apollo is the Albergo della Catena, an active inn from at least the 16th century until 1931 when it was bought by the city of Rome.