Archaeologists excavating the widely plundered Mycenaean-era cemetery in Aidonia, outside of Nemea in the Peloponnese region of southern Greece have discovered a fully intact, undisturbed tomb from the Early Mycenean period (1650-1400 B.C.). The ellipsoid chamber tomb is one of the largest ever found in Aidonia, measuring more than 20 feet at its widest points.

Archaeologists excavating the widely plundered Mycenaean-era cemetery in Aidonia, outside of Nemea in the Peloponnese region of southern Greece have discovered a fully intact, undisturbed tomb from the Early Mycenean period (1650-1400 B.C.). The ellipsoid chamber tomb is one of the largest ever found in Aidonia, measuring more than 20 feet at its widest points.

The cemetery was first discovered by looters in 1976 who plundered it with such ferocity that gun fights broke out between rival looting gangs. Local authorities were bribed and priceless archaeological treasures were secretly smuggled out of Greece, including stuffed in watermelons. When Greece put guards on the site and official excavations began in 1978, the looting petered off (although there is evidence that new tombs were plundered in the early 2000s).

The cemetery was first discovered by looters in 1976 who plundered it with such ferocity that gun fights broke out between rival looting gangs. Local authorities were bribed and priceless archaeological treasures were secretly smuggled out of Greece, including stuffed in watermelons. When Greece put guards on the site and official excavations began in 1978, the looting petered off (although there is evidence that new tombs were plundered in the early 2000s).

During those first excavations, 20 chamber tombs were found, 18 of them stripped bare by looters. The tombs were carved out of living rock and were consistent in design. They had three sections: the road leading to the tomb, the opening or entranceway and the burial chamber. Inside the burial chamber were multiple pits dug into the floor and covered with large stone slabs. These are where bodies were interred with their grave goods, often a rich assemblage of pottery, precious metals and jewelry.

During those first excavations, 20 chamber tombs were found, 18 of them stripped bare by looters. The tombs were carved out of living rock and were consistent in design. They had three sections: the road leading to the tomb, the opening or entranceway and the burial chamber. Inside the burial chamber were multiple pits dug into the floor and covered with large stone slabs. These are where bodies were interred with their grave goods, often a rich assemblage of pottery, precious metals and jewelry.

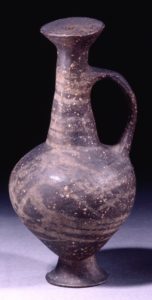

The newly-discovered tomb has four large pits carved into the floor, each covered with megalithic slabs. The earliest of the burials included clay tableware and storage vessels. They were decorated with stylized representations of plant and marine life, motifs typical of the “Palace Style” believed to be descended from Cretan art at Knossos. Archaeologists also discovered copper knives and swords, copper, obsidian and pyrite arrowheads, jewelry, an amethyst and gold bead necklaces, pins and seal stones.

The newly-discovered tomb has four large pits carved into the floor, each covered with megalithic slabs. The earliest of the burials included clay tableware and storage vessels. They were decorated with stylized representations of plant and marine life, motifs typical of the “Palace Style” believed to be descended from Cretan art at Knossos. Archaeologists also discovered copper knives and swords, copper, obsidian and pyrite arrowheads, jewelry, an amethyst and gold bead necklaces, pins and seal stones.

The tomb continued to be used into the late Mycenaean period (ca. 1400-1200 B.C.) when the deceased were interred on the floor of the tomb rather than in carved pits. These were more simple burials with little in the way of grave goods. The collapse of the stone roof of the tomb ended its reuse for new burials and obscured its location

The tomb continued to be used into the late Mycenaean period (ca. 1400-1200 B.C.) when the deceased were interred on the floor of the tomb rather than in carved pits. These were more simple burials with little in the way of grave goods. The collapse of the stone roof of the tomb ended its reuse for new burials and obscured its location  thereby protecting it from interference, not just from modern-day looters, but from successive occupiers of the site from the Classical period through the Roman Empire through the Late Byzantine. They all used the cemetery (not knowing that’s what it was) and built over the tomb. The subsequent deposits helped keep it safe, its contents intact for archaeologists to discover.

thereby protecting it from interference, not just from modern-day looters, but from successive occupiers of the site from the Classical period through the Roman Empire through the Late Byzantine. They all used the cemetery (not knowing that’s what it was) and built over the tomb. The subsequent deposits helped keep it safe, its contents intact for archaeologists to discover.