An extremely rare surviving feathered cloak from the northeast coast of Brazil has been restored and will go on display at the Pinacoteca Ambrosiana in Milan starting Tuesday, February 26th.

An extremely rare surviving feathered cloak from the northeast coast of Brazil has been restored and will go on display at the Pinacoteca Ambrosiana in Milan starting Tuesday, February 26th.

The cloak dates to between the late 16th and early 17th century. Triangular in shape and complete with a small hood that originally was decorated with yellow macaw feathers (now almost entirely lost), it was made by tying feathers to a net woven of cotton. Most of the feathers are bright orange-red plumes from the scarlet ibis. Yellow and blue accents were created with macaw feathers. The materials, cotton and feathers, are so delicate very few feathers cloaks have survived until our time. This is the only one known to have a distinctive geometric pattern on the back, believed to be a stylized line representation of a bird.

The Ambrosiana has held the mantle in its collection for almost its entire life. It was donated by Milanese cleric and collector Manfredo Settala (1600-1680). He was one of the greatest collectors in 17th century Europe, going far beyond the cabinet of curiosities popular among the aristocracy of the period into a full-on museum replete with art, ancient pottery, China, sculpture, exotic animals, fossils, shells, clocks, optical devices, corals, gemstones, minerals, jewelry, foodstuffs (nuts, beans, spices, cacao) skeletons, mummies and just about anything else you can imagine. His collection was so vast that the Bibliteca Ambrosiana was unable to accommodate Settala’s offer to donate it in its entirety because they didn’t have the space.

The Ambrosiana has held the mantle in its collection for almost its entire life. It was donated by Milanese cleric and collector Manfredo Settala (1600-1680). He was one of the greatest collectors in 17th century Europe, going far beyond the cabinet of curiosities popular among the aristocracy of the period into a full-on museum replete with art, ancient pottery, China, sculpture, exotic animals, fossils, shells, clocks, optical devices, corals, gemstones, minerals, jewelry, foodstuffs (nuts, beans, spices, cacao) skeletons, mummies and just about anything else you can imagine. His collection was so vast that the Bibliteca Ambrosiana was unable to accommodate Settala’s offer to donate it in its entirety because they didn’t have the space.

In a 1666 catalogue of the Settala Gallery, there was a whole chapter dedicated to “Pilgrim Curiosities of Indian Bird Feathers Ingeniously Woven.” The artifacts in this category include several Christian icons made of colored feathers in “Peru” (which may be more of a catch-all term for Spanish America rather than a specific origin), a belt and crown, a sash of Chilean ostrich feathers, another of “Indian crow” feathers “the color of fire.”

The mantle is described as an “Indian priestly vestment of sanguine color, a fiery weaving of many feathers naturally colored. A very remarkable work and worthy of being admired.” Settala had received it as a gift from Prince Federico Landi, scion of a noble family in northern Italy whose princely title had been granted by the Holy Roman Emperor. Landi was a political figure of some importance — he had ties to Philip III of Spain, Duke of Milan — and he and Settala shared an interest in collecting natural (and manufactured) wonders. His connection to the King of Spain likely provided him access to exceptional artifacts from Spain’s colonies. The feathered belt and crown in the Settala Gallery were donated by Prince Landi after Manfredo’s death in his memory.

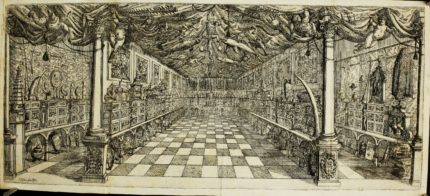

It’s not labelled so I don’t know for sure, but I believe the mantle, its hood still richly feathered, is hanging on the front right wall in this drawing of the Settala Gallery from the 1666 catalogue:

Settala’s own records identify the “ceremonial mantle” as having been created by the Tupinambá people of Brazil. They record that it was a gift from Prince Landi and note that the the Tupinambá wore these garments during a ceremony depicted in a drawing by Belgian engraver Theodor de Bry in the late 16th century. (De Bry’s works were based on the writings of other people; he never traveled across the Atlantic himself, and there are numerous errors, inconsistencies and scenes more dramatic than factual in his oeuvre.)

Early European accounts of encounters with the Tupinambá published in the second half of the 16th century describe multiple uses of feathers in adornment: boiled chicken feathers used in tattooing, Toucan feathers worn as ear pendants and ostrich feathers strung on cotton thread worn as hip belts.

These accounts often remarked on the Tupinambá people’s reluctance (read: refusal) to wear clothing no matter how hard the colonizers and converters tried. The few indigenous garments the population did enjoy were worn for ceremonial purposes and had nothing like the full coverage the priests were so anxious to instill. Headdresses, cloaks and sashes adorned with the brightly colored feathers of different native birds were highly prized and handled with utmost care to preserve them from wear and tear.

Researchers hypothesize that mantles like this one may have been used by priests during the most important ceremony to the Tupinambá community: a cannibalistic ritual in which the flesh of sacrificed prisoners of wars was consumed to give warriors access to a paradiasical “World without Evil” after death.