England and France may have had one or two little issues with each other in the Middle Ages, but all is forgiven now and 800 medieval illuminated manuscripts have been digitized and made available to the public on the websites of the British Library and Bibliothèque Nationale de France. The BL and BnF have the largest collections of medieval illuminated manuscripts in the world. To make some of these masterpieces accessible to the general public, both libraries worked together with funding from the Polonsky Foundation, a charitable organization that focuses on preserving and sharing cultural heritage primarily through the digitizing of important collections.

England and France may have had one or two little issues with each other in the Middle Ages, but all is forgiven now and 800 medieval illuminated manuscripts have been digitized and made available to the public on the websites of the British Library and Bibliothèque Nationale de France. The BL and BnF have the largest collections of medieval illuminated manuscripts in the world. To make some of these masterpieces accessible to the general public, both libraries worked together with funding from the Polonsky Foundation, a charitable organization that focuses on preserving and sharing cultural heritage primarily through the digitizing of important collections.

The carefully curated collection features works created in Medieval England and France between 700 and 1200 A.D.

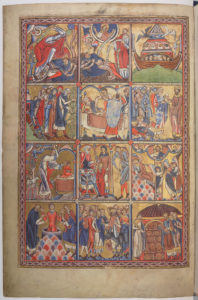

The manuscripts have been selected for their historical significance in terms of relations between France and England during the Middle Ages. They are also of unique artistic, historical or literary interest. Produced between the eighth and the end of the twelfth century, they cover a wide range of subjects, illustrating intellectual production during the early middle ages and the Roman period. Among these manuscripts are a few precious, sumptuously illuminated examples such as the Benedictional of Winchester around the year 1000, the Bible de Chartres around 1140 or the Great Canterbury Anglo-Catalan Psalter produced circa 1200.

With this corpus being of undisputable scientific interest, the programme is also characterised by several manuscript recovery operations: digitisation, online dissemination, restoration, scientific description and even mediation.

The BnF portal provides access to all 800 manuscripts. They are grouped according to themes, authors, places and centuries for ease of navigation and can be searched in English, French and Italian. The technical tools are downright nifty. Manuscripts can be viewed side-by-side for comparison. They can be annotated online and the annotations downloaded as json files for sharing. Manuscript pages can be downloaded as individual images or the entire manuscript can be download as a PDF.

The BnF portal provides access to all 800 manuscripts. They are grouped according to themes, authors, places and centuries for ease of navigation and can be searched in English, French and Italian. The technical tools are downright nifty. Manuscripts can be viewed side-by-side for comparison. They can be annotated online and the annotations downloaded as json files for sharing. Manuscript pages can be downloaded as individual images or the entire manuscript can be download as a PDF.

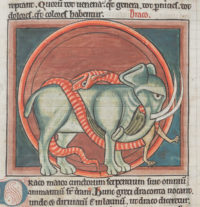

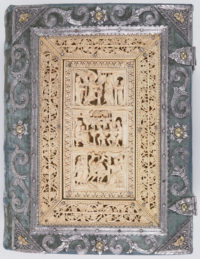

The BL portal presents a selection of manuscripts. Articles on subjects like medieval legal, medical and musical writing place the works in their historical context and significance. There are also pieces on the wider background of illumination, book-making, science and learning in the Middle Ages. A few of the manuscripts in the collection have been highlighted here, and boy are they showstoppers — lavish illustrations, intricately carved ivory and precious metal covers, hymnals, psalters and a phenomenal bestiary.

The BL portal presents a selection of manuscripts. Articles on subjects like medieval legal, medical and musical writing place the works in their historical context and significance. There are also pieces on the wider background of illumination, book-making, science and learning in the Middle Ages. A few of the manuscripts in the collection have been highlighted here, and boy are they showstoppers — lavish illustrations, intricately carved ivory and precious metal covers, hymnals, psalters and a phenomenal bestiary.