Archaeologists, architects and restorers working on the Domus Aurea have discovered a new room decorated with elegant frescoes. It has been dubbed the Hall of the Sphinx after one of the mythological creatures painted on the walls.

Archaeologists, architects and restorers working on the Domus Aurea have discovered a new room decorated with elegant frescoes. It has been dubbed the Hall of the Sphinx after one of the mythological creatures painted on the walls.

Nero’s megalomaniacally huge palace was so associated with the emperor and his worst impulses — how he used the Great Fire of 64 A.D. as an opportunity for an enormous land grab, his profligacy, his massive ego, his slothfulness — that after his suicide in 68 A.D. the Golden House was destroyed by Vespasian. Forty years after that, the emperor Trajan used the ruins as the foundation for a great public bath complex. He stripped the walls and floors of all remaining valuable materials (marble, mosaics, frescoes) and filled the vast open spaces of the rooms with rubble. Fallen walls were rebuilt in brick.

When the palace remains were rediscovered in the 15th century, nobody knew it was the Domus Aurea. They just thought they’d found caves (“grotte” in Italian), and, amazed by the delicacy and perspective of the frescoes, Renaissance artists like Raphael and Michelangelo lowered themselves in through holes in the ceiling to see the figures. The painting style inspired by the discovery of the palace became known as grotesque.

When the palace remains were rediscovered in the 15th century, nobody knew it was the Domus Aurea. They just thought they’d found caves (“grotte” in Italian), and, amazed by the delicacy and perspective of the frescoes, Renaissance artists like Raphael and Michelangelo lowered themselves in through holes in the ceiling to see the figures. The painting style inspired by the discovery of the palace became known as grotesque.

The tour of the Domus Aurea today, which I’ve done twice because I was so astonished by it the first time I went, includes a riveting virtual reality recreation of what the huge spaces of the palace looked like when the artists dropped in through an oculus to observe with wonder the ancient art on the walls. The Trajanic fill rose dozens of feet up the walls, leaving only the vaults empty. Many of those soaring spaces up to 36 feet high have been excavated since, and invaded with moisture, organic overgrowth and mineral deposits, the frescoes have lost much of the intensity that so inspired the Old Masters of the Renaissance. This find puts us in their shoes for the first time.

The hall was discovered during the installation of scaffolding to support the walls in Room 72. While up high, workers saw an aperture at the top of the north wall that was not visible from below. They looked through the hole, illuminating it with their lights, and saw a space filled with soil and rubble almost reaching its ceiling.

The room is rectangular, topped with a barrel vaulted ceiling. The ceiling and visible tops of the walls are decorated with frescoes in the grotesque style that inspired artists who had no idea they were in Nero’s ancient palace. Against the white background of the vault are panels outlined in ochre and red. The perimeter rectangle is yellow with foliate elements and curvilinear swirls at the four corners.

In center of the panels are figures painted in richly saturated lines: a man armed with a sword, quiver and shield confronting a panther, rampant centaurs, satyrs, fantastical aquatic creatures, garlands, branches covered in green, yellow and red leaves with birds perched on them. On the semi-circular lunette against the wall is an imaginary structure with columns topped by a gold patera (ceremonial dish). Beside it is a winged sphinx on a pedestal.

These types of figures and motifs are found in many other rooms of the Domus Aurea and can be identified as the output of Workshop A which was in operation between 65 and 68 A.D. The artists from this workshop employed white backgrounds, light architectural designs and small figures to create a spacious, luminous effect even in small poorly-lit rooms. The position of the room in contrast to the overall planning of the Domus indicates that this is one of the older, less known spaces of the palace. They weren’t newly built by Nero, but rather refurbished by him. Originally they were part of a Claudian-era warehouse. Nero had them gussied up and integrated in the Domus.

These types of figures and motifs are found in many other rooms of the Domus Aurea and can be identified as the output of Workshop A which was in operation between 65 and 68 A.D. The artists from this workshop employed white backgrounds, light architectural designs and small figures to create a spacious, luminous effect even in small poorly-lit rooms. The position of the room in contrast to the overall planning of the Domus indicates that this is one of the older, less known spaces of the palace. They weren’t newly built by Nero, but rather refurbished by him. Originally they were part of a Claudian-era warehouse. Nero had them gussied up and integrated in the Domus.

At first glance, the frescoes appeared to be in good condition, but a more in depth examination found the decoration was obfuscated by layers of salts, carbonation and film of biological organisms. There has also been significant pigment loss and lifting of the plaster from the preparatory layers on the wall. Some sections were almost completely detached from the wall and in imminent danger of collapse.

Conservation was a challenge because of the complex microclimatic conditions of the Domus Aurea, the limited height of the space, the difficulty in accessing it and the almost complete lack of air circulation. Restorers had to wear harnesses and were constantly monitored by support staff in Room 72. They put an air replacement system in place, but even with that the team decided not to use solvents or biocidal products that could be dangerous in such an enclosed space and that could alter the heat and moisture balance of the environment.

Conservators triaged the frescoes and focused on the areas in most urgent need of stabilization. They repaired what they could using materials like grout that have good adhesive power with little fluidity to prevent any infiltration of the interior wall.

There are no plans to excavate the room. After almost 2000 years, that fill Trajan crammed in there is structural.

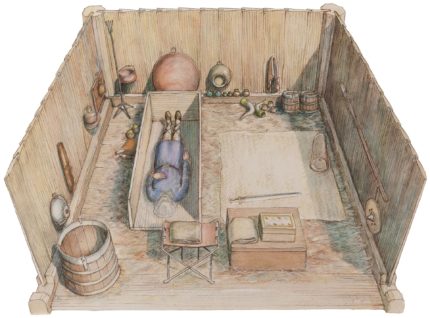

Metal detector enthusiasts discovered a hoard of Roman copper coins near the village of Rauceby in Lincolnshire in July of 2017. They had searched the area for years with only a few minor finds to show for it. This time when their detectors signaled the presence of metal, when they dug they found a massive quantity of Roman coins.

Metal detector enthusiasts discovered a hoard of Roman copper coins near the village of Rauceby in Lincolnshire in July of 2017. They had searched the area for years with only a few minor finds to show for it. This time when their detectors signaled the presence of metal, when they dug they found a massive quantity of Roman coins.Dr Daubney commented: “The coins were found in a ceramic pot, which was buried in the centre of a large oval pit – lined with quarried limestone. What we found during the excavation suggests to me that the hoard was not put in the ground in secret, but rather was perhaps a ceremonial or votive offering. The Rauceby hoard is giving us further evidence for so-called ‘ritual’ hoarding in Roman Britain.”

The coins were officially declared treasure under the terms of the 1996 Treasure Act by the Lincoln Coroner’s Court on May 9th. The hoard is in the British Museum right now for assessment by the valuation committee. Once fair market value is assessed, local museums will be given first crack at acquiring the hoard by paying the assessed value in compensation to be split 50/50 by the finders and landowner. In this case the value will likely be in the tens of thousands of pounds.

The coins were officially declared treasure under the terms of the 1996 Treasure Act by the Lincoln Coroner’s Court on May 9th. The hoard is in the British Museum right now for assessment by the valuation committee. Once fair market value is assessed, local museums will be given first crack at acquiring the hoard by paying the assessed value in compensation to be split 50/50 by the finders and landowner. In this case the value will likely be in the tens of thousands of pounds.