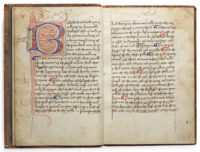

UK Arts Minister Helen Whately has blocked export of a unique 15th century Middle English manuscript. The Speculum Inclusorum (the Mirror of Recluses) was written by an unknown author as a manual for women who chose to become anchorites, a type of religious recluse that gained some popularity in medieval England.

UK Arts Minister Helen Whately has blocked export of a unique 15th century Middle English manuscript. The Speculum Inclusorum (the Mirror of Recluses) was written by an unknown author as a manual for women who chose to become anchorites, a type of religious recluse that gained some popularity in medieval England.

Anchorites dedicated their lives to god by enclosing themselves in a small cell attached to a church. They were usually lay people, not nuns or priests, who chose isolation and self-abnegation inspired by the example of the ascetic Desert Fathers of the 3rd century. Instead of the sacrament of Holy Orders received by priests or the symbolic Marriage to Christ of nuns, anchorites received an enclosure service modeled on the mass said for the dead. The officiant even sprinkled the anchorite with dirt reciting the “ashes to ashes” bit, just like with a casket at a funeral.

The place in which they would be enclosed for life was known as the anchorhold. It had three windows: one slit through which they could observe mass and take communion, one through which servants would deliver food and remove waste, one to the outside world to receive visitors or the sacrament of Confession. While visitors were very rare — the whole point was to be a recluse living a life of isolation, denial and prayer — anchorites were considered extra holy for having chosen enclosure and pilgrims did seek out their council. Julian of Norwich (1342-ca. 1420), an anchoress and author of the oldest surviving English book written by a woman (Revelations of Divine Love), was a spiritual adviser to, among others, Margery Kempe, author of the first autobiography written in English.

Once enclosed in their anchorhold, that was that. There was no leaving the 12×12-foot room, nor any way out even if they’d wanted to. It was referred to as a tomb and that wasn’t just a metaphor. Some had literal graves dug in the ground, open and in full view of the anchorite who for the duration of her entombed life could contemplate the actual tomb she’d occupy when that life was over. (The practice of burying anchorites in their anchorholds appears to have petered off in the 14th century, replaced by churchyard burials.)

As extreme a lifestyle as it was, it was a bit of a trend in the Middle Ages. Researchers have traced about 100 anchorites in 12th century England, and the figure doubles to 200 between the 13th and 15th centuries. Women were particularly drawn to enclosure. There were three times as many anchoresses as anchorites in the 13th century, and twice as many in the 14th and 15th centuries. These were people of means. They had to apply for the position to the bishop and prove they had the financial wherewithal to support themselves for the duration of their enclosure, be it long or short. They paid all costs — food, clothes, furnishings, attendants — which could add up over decades even for the most ascetic anchorite.

They were also more likely to be literate, and a number of guides were written to acquaint the would-be anchorite with their new way of life. The Ancrene Wisse, an anonymous manuscript in Middle English from the early 13th century, advises anchorites not to eat with visitors because it’s too familiar and too unlike the unworldly dead they’re supposed to be, to avoid being vain about their lily-white hands by digging up the dirt floor of their anchorholds “from the grave in which they will rot.” On the plus side, the author recommends against mortification of the flesh via self-flagellation with lead whips, holly or brambles, or by wearing iron, hair or hedgehog skin shirts. (This is the first I’ve heard of hedgehog skin shirts. Presumably worn spines-in for maximum pain. Puts regular hair shirts to shame.)

The Mirror of Recluses was written two centuries later and is specifically directed to women embracing enclosure. Only one other copy was known to exist before the export-barred manuscript appeared at auction in 2014. It is in the collection of the British Library and it is incomplete. The prologue is missing as is a third of the rest of the book.

Being unique and previously unknown, the prologue is of central importance for understanding the origin and authorship of the translation. It provides for the first time a precise date for the work: ‘This Wednysday bi the morow the even of the blissed virgyne seynt Alburgh the secunde yeere of the worthy christen prince kyng Henry the fift’ (i.e. 1414). The wording of the prologue suggests that the manuscript was written within a few years of 1414, because it continues ‘Whos longe lif and hy prosperite the kynge of al kynges kepe and maynten for the sure and holsum governaunce of this regioun’, which strongly suggests that Henry V was still alive, and would thus date the manuscript before his death in 1422. W.W. Skeat’s initial opinion was that, ‘it is an original of the date it professes to be’ (f.iii), but he subsequently felt that it was mid-century.

The location where the author was writing is perhaps suggested by his repeated references to St ‘Alburgh’: in addition to his dating clause cited above, he mentions ‘oure lady seynt Marie and of my forsaide lady seynt Alburgh’. She must be one of two saints: either Alburga/Aethelburh/Ethelburga of Wilton or, more likely, the saint of the same name of Barking (it cannot be Ethelburga of Kent, who was married, not a virgin), each of whom was an abbess of a nunnery. The morrow (day after) the 11 October feast of Ethelburga of Barking was indeed a Wednesday in 1414 (but so too was the day after the 25 December feast of Ethelburga of Wilton, so at present it is difficult to know conclusively which saint and feast-day is being referred to).

The Reviewing Committee on the Export of Works of Art and Objects of Cultural Interest (RCEWA) recommended that export be barred because of its irreplaceable value to scholarship.

Committee Member Leslie Webster said:

Unknown to scholarship until recently, this handsomely decorated copy of a guide to the austere life of an anchorite offers a rich new avenue of exploration into the nature of women’s religious education in the early fifteenth century, and how such texts were circulated. Almost certainly written for female anchorites, the text seems to be linked to the Benedictine nuns at Barking Abbey, a foundation dating back to Anglo-Saxon times, and in the fifteenth century, renowned as a house of educated women, inspired by its Abbess, Sybil de Felton.

Amongst other unique content, this particular manuscript also gives a precise date for the beginning of the text’s composition: ‘this Wednysday bi the morrow, the even of the blissed virgyne seynt Alburgh, the secunde yeere of the worthy christen prince oure souerayn liege lord the kyng Henry the Fiftis’ – or Wednesday, 10 October 1414. Such contemporary detail makes the manuscript a vivid witness to the period, as well as of great importance to our understanding of later medieval thought and society. It is a fascinating treasure that deserves to be saved.

The export license will be deferred until April 13th to give local institutions the chance to raise the purchase price of £168,750. That can be extended to August if someone shows serious intent to raise the money.