Napoleon’s forces occupied Rome twice. The first time was in February 1798 when General Louis Alexandre Berthier invaded the Papal States and Rome, for the first time since antiquity, was declared a republic, one of multiple “sister republics” established by Revolutionary France under the aegis of the Directory. The republic lasted barely a year (the Directory would follow it into the grave before 1799 was out) before the Kingdom of Naples invaded the city and reestablished the Papal States. On February 2nd, 1808, the French army under General Alexandre de Miollis (who also fought in the American Revolutionary War) took Rome again. He remained as governor of the former Papal States until Napoleon’s exile to Elba in 1814.

Napoleon’s forces occupied Rome twice. The first time was in February 1798 when General Louis Alexandre Berthier invaded the Papal States and Rome, for the first time since antiquity, was declared a republic, one of multiple “sister republics” established by Revolutionary France under the aegis of the Directory. The republic lasted barely a year (the Directory would follow it into the grave before 1799 was out) before the Kingdom of Naples invaded the city and reestablished the Papal States. On February 2nd, 1808, the French army under General Alexandre de Miollis (who also fought in the American Revolutionary War) took Rome again. He remained as governor of the former Papal States until Napoleon’s exile to Elba in 1814.

Between the first and second French occupation of Rome, Napoleon had gone from General to First Consul to Emperor and was at the apex of his career in conquest. On May 16th, 1809, he promulgated an imperial decree declaring the annexation of the Papal States to the French Empire. Rome was declared “a free and imperial city.” On Feburary 17th, 1810, Napoleon declared Rome the second city of the empire, subject to receive special privileges determined by the emperor himself. Any future imperial prince would receive the title and honors of “King of Rome.” A year later Napoleon’s wife Marie Louise of Austria gave birth to Napoléon-François-Joseph-Charles Bonaparte and the first King of Rome since Tarquin the Proud came into his title.

Between the first and second French occupation of Rome, Napoleon had gone from General to First Consul to Emperor and was at the apex of his career in conquest. On May 16th, 1809, he promulgated an imperial decree declaring the annexation of the Papal States to the French Empire. Rome was declared “a free and imperial city.” On Feburary 17th, 1810, Napoleon declared Rome the second city of the empire, subject to receive special privileges determined by the emperor himself. Any future imperial prince would receive the title and honors of “King of Rome.” A year later Napoleon’s wife Marie Louise of Austria gave birth to Napoléon-François-Joseph-Charles Bonaparte and the first King of Rome since Tarquin the Proud came into his title.

The February 17th decree also committed to maintaining Rome’s ancient monuments at the empire’s expense, and a special fund was created to support archaeological excavations, restorations and “embellishments of Rome.” The Forum was excavated and cleared, remains like what was then believed to be the Temple of Jupiter Tonans (the Thunderer) but is in fact the temple of the deified emperors Vespasian and Titus were liberated from the soil encasing 2/3rds of their height.

The February 17th decree also committed to maintaining Rome’s ancient monuments at the empire’s expense, and a special fund was created to support archaeological excavations, restorations and “embellishments of Rome.” The Forum was excavated and cleared, remains like what was then believed to be the Temple of Jupiter Tonans (the Thunderer) but is in fact the temple of the deified emperors Vespasian and Titus were liberated from the soil encasing 2/3rds of their height.  Excavations at the Colosseum revealed for the first time its elaborate underground structures whose purpose was subject of great controversy and heated debate between architects, antiquarians, archaeologists and historians. Later homes and religious buildings squashed up against Trajan’s Column were Trajan’s Column to allow it to stand out. The Basilica Ulpia was rediscovered at the same time.

Excavations at the Colosseum revealed for the first time its elaborate underground structures whose purpose was subject of great controversy and heated debate between architects, antiquarians, archaeologists and historians. Later homes and religious buildings squashed up against Trajan’s Column were Trajan’s Column to allow it to stand out. The Basilica Ulpia was rediscovered at the same time.

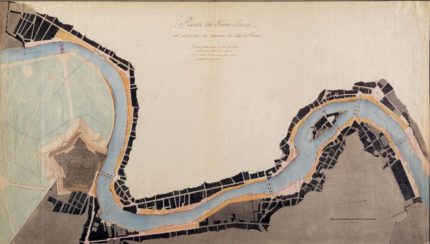

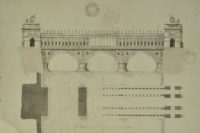

The Napoleonic administration wasn’t just about reviving Rome’s ancient splendors. There were plans for the emperor and the King of Rome to visit the city and they wanted to welcome them into a modern imperial capital with wide boulevards, green spaces and grand buildings. Prominent Roman architects like Giuseppe Valadier and Giuseppe Camporese and French ones like Louis-Martin Berthault and Guy de Gisors were commissioned to design urban renewal projects — parks, bridges, new monuments, securing the banks of the Tiber to prevent flooding — and just outside of the city, new cemeteries to comply with the Napoleon’s 1804 edict prohibiting burials within city walls.

The Napoleonic administration wasn’t just about reviving Rome’s ancient splendors. There were plans for the emperor and the King of Rome to visit the city and they wanted to welcome them into a modern imperial capital with wide boulevards, green spaces and grand buildings. Prominent Roman architects like Giuseppe Valadier and Giuseppe Camporese and French ones like Louis-Martin Berthault and Guy de Gisors were commissioned to design urban renewal projects — parks, bridges, new monuments, securing the banks of the Tiber to prevent flooding — and just outside of the city, new cemeteries to comply with the Napoleon’s 1804 edict prohibiting burials within city walls.

None of these plans came to fruition before the fall of Napoleon in 1814. Sketches, plans and watercolors are all that remains of the emperor’s new Rome. Very few of them have been studied. Most of them have never been published. Now more than 50 works from the collections of Rome’s Napoleonic Museum and the Museum of Rome at Palazzo Braschi have gone on display at the Napoleonic Museum.

Waiting for the Emperor: Monuments Archaeology and Urbanism in the Rome of Napoleon 1809-1814, looks at city as it was in the age of Napoleon, the exhuberant celebrations in the city for the birth of the King of Rome, archaeological digs and monumental projects (statues, arches of triumph, bridges) to create a modern imperial Rome inspired by the ancient one.

I’m intrigued by this might-have-been Napoleonic plan for the Tiber.

After a massive flood on December 28th, 1870, when the river’s water rose more than 56 feet (17.22 meters) above the banks, made the new capital of a fully unified Italy a stinky, soggy muckhole just in time for the visit of the first king of Italy, Vittorio Emanuele II, the government built stone embankments 59 feet (18 meters) high. They largely solved the flooding problem, but they drastically altered the city’s relationship with its river, instantly transmuting it from the beating heart of the community to a forbidding, disconnected environment, and not a little scary.

The exhibition runs through May 31st, 2020.