A new avian dinosaur has been identified from its tiny skull preserved in amber from Myanmar. The 99-million-year-old amber was discovered in 2016 and the long-beaked, big-eyed, toothy skull encased within has gotten a new name: Oculudentavis khaungraae. It is one of the smallest dinosaurs ever found the second most ancient bird after Archaeopteryx.

A new avian dinosaur has been identified from its tiny skull preserved in amber from Myanmar. The 99-million-year-old amber was discovered in 2016 and the long-beaked, big-eyed, toothy skull encased within has gotten a new name: Oculudentavis khaungraae. It is one of the smallest dinosaurs ever found the second most ancient bird after Archaeopteryx.

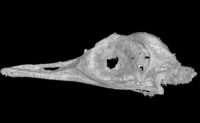

The entire skull is just 1.5cm (.6 inches) long. Extrapolating from that, Oculudentavis was no more than 1.6 inches long from the tip of its beak to the tip of its tail, comparable in size to the bee hummingbird, the smallest bird alive today. In order to study the fossil in detail without damaging the  amber, the research team used high-resolution X-ray images to create a 3D model. This creature was bird-like but not a bird, a dinosaur but not like any other known.

amber, the research team used high-resolution X-ray images to create a 3D model. This creature was bird-like but not a bird, a dinosaur but not like any other known.

First of all, the skull seems to be built for strength. The bones show an unusual pattern of fusion and the skull lacks an antorbital fenestra, a small hole often found in front of the eye.

The eyes of Oculudentavis also surprised us. The shape of the bones found within the eye, the scleral ossicles, suggests that it probably had conical eyes with small pupils. This type of eye structure is especially well adapted for moving around in bright light. While daytime activity might be expected for an ancient bird from the age of dinosaurs, the shape of the ossicles is entirely distinct from any other dinosaur and resembles those of modern-day lizards.

Adding to the list of unexpected features, the upper jaw carries at least 23 small teeth. These teeth extend all the way back beneath the eye and are not set in deep pockets, an unusual arrangement for most ancient birds. The large number of teeth and their sharp cutting edges suggest that Oculudentavis was a predator that may have fed on small bugs.

The sum of these traits – a strong skull, good eyesight and a hunter’s set of teeth – suggests to us that Oculudentavis led a life previously unknown among ancient birds: it was a hummingbird-sized daytime predator.

If the research team is correct about Oculudentavis‘ age and position on the evolutionary timeline, it rewrites what we know about how and when the large reptiles transitioned into the birds that are their living descendants today. Oculudentavis predates the appearance of nectar-feeding hummingbirds by 70 million years, which means the tiny dinosaurs and the massive ones lived together at the same time.

The study has been published in the journal Nature.