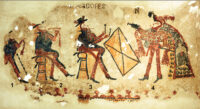

Venerable automaker Alfa Romeo celebrates its 110th anniversary in less than 10 days. In honor of the occasion, the company has released an e-book about its history from car models to its iconic logo incorporating the famous dragon eating a man, the emblem of the Visconti family which once ruled the city of Milan.

Venerable automaker Alfa Romeo celebrates its 110th anniversary in less than 10 days. In honor of the occasion, the company has released an e-book about its history from car models to its iconic logo incorporating the famous dragon eating a man, the emblem of the Visconti family which once ruled the city of Milan.

The first car was manufactured in 1910 when the company was still an acronym, A.L.F.A. (Anonima Lombarda Fabbrica Automobili, meaning “Lombard Automobile Factory, Public Company”). The 42 HP could reach an impressive-for-the-time top speed of 62 miles per hour. Fifty of them were sold in the first year. The engine was

The first car was manufactured in 1910 when the company was still an acronym, A.L.F.A. (Anonima Lombarda Fabbrica Automobili, meaning “Lombard Automobile Factory, Public Company”). The 42 HP could reach an impressive-for-the-time top speed of 62 miles per hour. Fifty of them were sold in the first year. The engine was  strong enough to power a prototype biplane made of bicycle tubes.

strong enough to power a prototype biplane made of bicycle tubes.

A.L.F.A. built on the success of the 42 HP and quickly grew. By 1915 it had 2,500 employees manufacturing three models. Then came World War I. The factory was converted to wartime production — aircraft engines, munitions, compressors — until 1919 when Alfa resumed car production. With the new cars came a new name as Nicola Romeo, an engineer and entrepreneur who had acquired a majority of shares in 1915 and all of them by 1918, added his name to the brand. The first car to come off the line bearing the Alfa Romeo imprimatur was the 1921 Torpedo 20/30 HP.

This was the decade when Alfa made its bones in racing. Its first racing team included a certain Enzo Ferrari as a driver. Alfa’s innovations won it the most prestigious races of the time, the Le Mans, Mille Miglia and a myriad Grands Prix. They also made for some amazing looking cars, ones like the Tipo B Aerodinamica (1934) and the 8C 2900 Le Mans (1938) that wouldn’t be remotely out of place in a superhero’s secret cave lair.

This was the decade when Alfa made its bones in racing. Its first racing team included a certain Enzo Ferrari as a driver. Alfa’s innovations won it the most prestigious races of the time, the Le Mans, Mille Miglia and a myriad Grands Prix. They also made for some amazing looking cars, ones like the Tipo B Aerodinamica (1934) and the 8C 2900 Le Mans (1938) that wouldn’t be remotely out of place in a superhero’s secret cave lair.

Automobile production came to a halt again during the Second World War, but when it resumed in April 1945, it resumed with a bang. The first post-war Alfa Romeo was the Freccia d’Oro (Golden Arrow) produced in 1947 and beloved by crowned heads and Hollywood stars alike. Icons like the Spider and Giulia followed.

Automobile production came to a halt again during the Second World War, but when it resumed in April 1945, it resumed with a bang. The first post-war Alfa Romeo was the Freccia d’Oro (Golden Arrow) produced in 1947 and beloved by crowned heads and Hollywood stars alike. Icons like the Spider and Giulia followed.

But it’s the prototypes that thrill me the most. The 1952 prototype Disco Volante (“flying saucer”) really does look like it should be dropping from the belly of a mothership. The greatest discovery in this ebook for me, however, is the 40-60 HP “Aerodinamica,” which was a private commission from Count Marco Ricotti in 1914. It was made entirely of lightweight aluminum and was shaped like a torpedo with porthole-style windows. The chassis and engine were exactly the same as the ones in the 40-60 HP production series, but the body was a pioneering attempt to harness the principles of aviation design for a land-going vehicle. It could reach a top speed of 86 mph, 12 miles faster than the standard 40-60 HP, thanks to its unique body confirmation. The tear-drop shape earned it the moniker Siluro (“torpedo”) Ricotti.

But it’s the prototypes that thrill me the most. The 1952 prototype Disco Volante (“flying saucer”) really does look like it should be dropping from the belly of a mothership. The greatest discovery in this ebook for me, however, is the 40-60 HP “Aerodinamica,” which was a private commission from Count Marco Ricotti in 1914. It was made entirely of lightweight aluminum and was shaped like a torpedo with porthole-style windows. The chassis and engine were exactly the same as the ones in the 40-60 HP production series, but the body was a pioneering attempt to harness the principles of aviation design for a land-going vehicle. It could reach a top speed of 86 mph, 12 miles faster than the standard 40-60 HP, thanks to its unique body confirmation. The tear-drop shape earned it the moniker Siluro (“torpedo”) Ricotti.

Alas, Count Ricotti chose … poorly. He had the car modified, some might say butchered, into a goofy roofless excursion vehicle. What was left of it after that did not survive. Alfa Romeo sought to remedy this cruel state of affairs and in 1979 commissioned an exact replica of the great Siluro recreated from the original designs. Recreating that torpedo body was more challenging as it had been produced by a separate company, the Carrozzeria Castagna, and no original designs for it exist. The Carrozzeria Castagna did have a photo in its archives of the Siluro’s manufacture, which gave the reconstruction team the information needed to replicate an accurate skeleton and external form. The new Siluro, a copy of the original in all its details including the unbelievable “damascene” finish of the aluminum, is now on display at the Alfa Romeo Museum in Arese, Milan. The museum reopens after the long Italian lockdown on June 24th, Alfa Romeo’s 110th birthday.

Alas, Count Ricotti chose … poorly. He had the car modified, some might say butchered, into a goofy roofless excursion vehicle. What was left of it after that did not survive. Alfa Romeo sought to remedy this cruel state of affairs and in 1979 commissioned an exact replica of the great Siluro recreated from the original designs. Recreating that torpedo body was more challenging as it had been produced by a separate company, the Carrozzeria Castagna, and no original designs for it exist. The Carrozzeria Castagna did have a photo in its archives of the Siluro’s manufacture, which gave the reconstruction team the information needed to replicate an accurate skeleton and external form. The new Siluro, a copy of the original in all its details including the unbelievable “damascene” finish of the aluminum, is now on display at the Alfa Romeo Museum in Arese, Milan. The museum reopens after the long Italian lockdown on June 24th, Alfa Romeo’s 110th birthday.