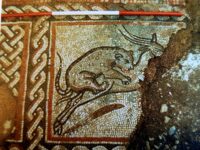

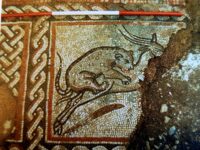

A fragment of a 4th century Romano-British mosaic depicting a leopard attacking a gazelle has been temporarily prevented from leaving Britain. Culture Minister Caroline Dinenage placed a temporary export bar on the artwork because it has been deemed an exceptional work from the Durnovarian (modern-day Dorchester) school of mosaicists. It hadn’t even left the county of Dorset for 1,700 years until it took a brief trip to London in 2019, so this would be a drastic move.

A fragment of a 4th century Romano-British mosaic depicting a leopard attacking a gazelle has been temporarily prevented from leaving Britain. Culture Minister Caroline Dinenage placed a temporary export bar on the artwork because it has been deemed an exceptional work from the Durnovarian (modern-day Dorchester) school of mosaicists. It hadn’t even left the county of Dorset for 1,700 years until it took a brief trip to London in 2019, so this would be a drastic move.

The leopard and gazelle pattern, guilloche pattern borders and small pieces of three adjacent panels were discovered between 1972 and 1974 during excavations of the Roman villa in Dewlish, Dorset. It was part of the  pavement of Room 11, a large room that has an unusual rounded apse and was the largest room in the house. The villa replaced a 3rd century farmhouse and was expanded and upgraded in various phases of construction. The refurbishment of Room 11 took place in the second half of the 4th century and added the apse, hypocaust underfloor heating and the finest mosaics available in the county. Its most glamorous phase lasted only a few decades. Postholes in some of the mosaics found in the house indicate clumsy attempts to prop the roof up so it seems the fancy villa was dilapidated by the end of the century.

pavement of Room 11, a large room that has an unusual rounded apse and was the largest room in the house. The villa replaced a 3rd century farmhouse and was expanded and upgraded in various phases of construction. The refurbishment of Room 11 took place in the second half of the 4th century and added the apse, hypocaust underfloor heating and the finest mosaics available in the county. Its most glamorous phase lasted only a few decades. Postholes in some of the mosaics found in the house indicate clumsy attempts to prop the roof up so it seems the fancy villa was dilapidated by the end of the century.

Its existence had passed into oblivion when Dewlish House, a handsome Grade I-listed Queen Anne/Georgian mansion, was built on the site in 1702 by Thomas Skinner. The remains of the Roman villa were first discovered there in 1740 when a storm uprooted a tree in the garden. The finds were poorly documented, but were contemporary reports say they included a mosaic. The remains were left open to the depredations of the curious and cupidinous and dug up further in 1790. Again, documentation was all but nonexistent. In the 19th and 20th centuries, the grounds were further churned up by agricultural work.

Its existence had passed into oblivion when Dewlish House, a handsome Grade I-listed Queen Anne/Georgian mansion, was built on the site in 1702 by Thomas Skinner. The remains of the Roman villa were first discovered there in 1740 when a storm uprooted a tree in the garden. The finds were poorly documented, but were contemporary reports say they included a mosaic. The remains were left open to the depredations of the curious and cupidinous and dug up further in 1790. Again, documentation was all but nonexistent. In the 19th and 20th centuries, the grounds were further churned up by agricultural work.

The estate was commandeered for the first wave of US Marines who made their base there in preparation for D-Day. After the war the family attempted to lease it, but there were no takers and by the early 1960s it was in such terrible disrepair that it was slated for demolition. It was purchased in 1962 by financier Anthony Boyden who restored the derelict structure to its former splendor.

The first modern archaeological excavation took place in 1969. Led by Bill Putnam, that first dig was just a 4-day fieldwork project for his archaeology students, but it evolved into a decade-long survey that uncovered, among other treasures, the remains of exquisite mosaic floors in several rooms.  The leopard and gazelle fragment was raised, mounted and apparently presented to the homeowner as a way-too-nice thank you gift for letting them excavate. This was unfortunately legal in the early 1970s. A few sections of the remaining mosaics were given to the Dorset County Museum. The rest of the mosaics Putnam’s team unearthed were reburied.

The leopard and gazelle fragment was raised, mounted and apparently presented to the homeowner as a way-too-nice thank you gift for letting them excavate. This was unfortunately legal in the early 1970s. A few sections of the remaining mosaics were given to the Dorset County Museum. The rest of the mosaics Putnam’s team unearthed were reburied.

The Dewlish House mosaic fragment was acquired at Duke’s Auction in September 2018 by antiques dealer Edward Hurst for £30,000. He exhibited at the 2019 Masterpiece London art fair and appears to have resold it for a tidy profit as the export license request places its value at £135,000.

The Minister’s decision follows the advice of the Reviewing Committee on the Export of Works of Art and Objects of Cultural Interest (RCEWA). The committee noted that there were few mosaics from the Durnovarian school showing this quality and exceptional workmanship. It was also widely agreed that there was much to be learned about Romano-British mosaics from further research and study of the fragment.

The RCEWA made its recommendation on the grounds of the mosaic’s outstanding significance to the study of Romano-British art and history.

Committee member Leslie Webster said:

“The mosaic‘s spirited depiction of a leopard bringing down an antelope is a brilliantly accomplished image of nature red in tooth and claw; the soaring leap of the deer, and the precise delineation of the leopard’s muscular power and ferocious grace is a tour de force of the mosaicist’s art. Such a resonant image, with its origins in the art and mythology of the classical world and beyond, has travelled a long way to Dorset, to feature in the villa of a wealthy Romano-British landowner; it must have been the latest thing in up-market house decoration. The grand mosaic from which this fragment came, dominating the principal public room of the villa, was clearly designed to impress the spectator with the learning and cultural aspirations of its owner. Perhaps this exotic symbol of the hunt, popular elsewhere in the Empire but exceptional in Britain, and its implicit theme of domination, were also intended to suggest its owner’s status and power.”

“In the later years of the Roman era in Britain, the representational innovation and technical sophistication of this mosaic, and of others produced by the Dorchester school of mosaicists, give fascinating insight into the lives of local Roman magnates, in a period seen as one of change and decline; they open up many questions and opportunities for investigation. For us to lose it from Britain would be a great misfortune.”

I suspect the mosaic fell victim to downsizing as Dewlish House, with all its outbuildings, cottages and its magnificent 134 acre park, was put on the market in 2019. It’s still available today for the bargain price (seriously, I’d pay it if I had it, no haggling or anything) of £9,250,000.

A salvage archaeology excavation in Chur, the capital of the Swiss canton of Grisons, have unearthed a stone jewelry mold and other evidence of a busy medieval artisan district. The molds was used to produce jewelry and religious objects. It is an extremely rare find, the first of its kind in the canton. The only comparable examples ever found in Switzerland were discovered far to the north and northwest of Grisons in Bern, Basel, and Winterthur.

A salvage archaeology excavation in Chur, the capital of the Swiss canton of Grisons, have unearthed a stone jewelry mold and other evidence of a busy medieval artisan district. The molds was used to produce jewelry and religious objects. It is an extremely rare find, the first of its kind in the canton. The only comparable examples ever found in Switzerland were discovered far to the north and northwest of Grisons in Bern, Basel, and Winterthur. Archaeologists have been excavating the area near the former Sennhof penitentiary since March in advanced of a renovation. Two previous excavations in 1984 and 1990 discovered the remains of settlements and tombs that confirm the area was continuously inhabited from the late Bronze Age through the present. This year’s excavation has shed light on the medieval city.

Archaeologists have been excavating the area near the former Sennhof penitentiary since March in advanced of a renovation. Two previous excavations in 1984 and 1990 discovered the remains of settlements and tombs that confirm the area was continuously inhabited from the late Bronze Age through the present. This year’s excavation has shed light on the medieval city. The jewelry mold is now undergoing thorough study and analysis for scientific publication. The objects discovered in the excavation are tentatively scheduled to go on public display in an exhibition, Commerce and Artisanship between the Lake of Constance and the Alpine Rhine, at the Chur museum in 2023.

The jewelry mold is now undergoing thorough study and analysis for scientific publication. The objects discovered in the excavation are tentatively scheduled to go on public display in an exhibition, Commerce and Artisanship between the Lake of Constance and the Alpine Rhine, at the Chur museum in 2023.