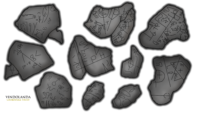

Two 15th century battle axes have been discovered at the site of the Battle of Grunwald in northern Poland. The axes are similar but not identical. One has a longer shaft of a closed type, meaning there’s a dedicated compartment for the handle. The other has a shorter open shaft.

Volunteers have come from all over Europe to survey the battlefield site every year for the past seven years. This year 70 volunteer metal detectorists explored the fields and marshes under the supervision of archaeologists. One of them, Aleksander Miedwiedew, discovered the axe heads in marshy ground about 30 inches below the surface. The waterlogged soil helped protect the axes from corrosion, leaving them in exceptional condition, complete with the original rivets that fastened the  axes to their wooden handles.

axes to their wooden handles.

According to Dr. Szymon Dreja, director of the Museum of the Battle of Grunwald, the discovery of the battle axes are an archaeological sensation.

“In seven years of our archaeological research we have never had such an exciting, important and well-preserved find,” he stressed.

The Battle of Grunwald took place on July 15th, 1410, during the Polish-Lithuanian-Teutonic War. Allied Polish and Lithuanian forces squared off against the German Teutonic Knights in massive forces, more than 50,000 fighters all told, making it one of the biggest battles in medieval Europe, if not the biggest. The Polish-Lithuanian side was victorious and delivered so sound a spanking that almost all of the Teutonic leadership either died on the field or was taken as prisoner of war. This was the turning point not just  for the war, but for the Teutonic Order itself which never recovered militarily from the defeat and whose economic power over its monastic state was obliterated by reparations after the war.

for the war, but for the Teutonic Order itself which never recovered militarily from the defeat and whose economic power over its monastic state was obliterated by reparations after the war.

This year’s archaeological survey of the battlefield also unearthed several dozen other weapon parts, most of them spear heads.

The museum is not revealing the precise location of the find because they believe that other artefacts are still lying in the ground. For this reason, they are planning more archaeological excavations later this year.

The mystery still waiting to be discovered is the location of the mass grave of knights who died in one of the greatest battles of medieval Europe.