Coventry’s 14th century civic sword has returned to its hometown 550 years after it was removed by an angry king. The sword, or rather, the hilt and a tiny stump of the blade which are all that survive, is part of the Burrell Collection art museum in Glasgow and has been loaned to Coventry for its City of Culture 2021 exhibition.

Coventry’s 14th century civic sword has returned to its hometown 550 years after it was removed by an angry king. The sword, or rather, the hilt and a tiny stump of the blade which are all that survive, is part of the Burrell Collection art museum in Glasgow and has been loaned to Coventry for its City of Culture 2021 exhibition.

Carrying a sword in front of a king during processions, coronations and other official occasions was an unambiguous symbol of supreme temporal power in the Middle Ages. The right to a bearing-sword was sometimes extended to powerful nobles (dukes and earls) and by the late 14th century, to mayors of cities. It was a recognition of the growing importance of cities to the monarch, a ceremonial honor that lent city government an aristocratic cachet even as it became a symbol of their civic liberties. London was the first to receive the grant of a mayoral sword. By 1500, 17 cities in England and its overseas possessions (Calais in 1392, Dublin in 1403 and Drogheda in 1468) had been granted civic swords.

We don’t know the precise date when Coventry was granted its civic sword, but it was before 1384 because the City Annals (compiled many centuries later) note that in that year Richard II ordered that the sword be carried behind the mayor instead of in front of him as punishment because the mayor “did not do justice.” Richard restored the mayor of Coventry’s right to carry the sword in front in 1387. Chronicler Henry Knighton of Leicester writing at that time described the Coventry sword as “gladium ornatu aureo” (sword decorated with gold). This is the earliest surviving contemporary record of a civic sword in Britain.

By the 14th century, Coventry was the fourth largest city in England. It was rich in natural resources — timber, stone, arable land, pastures for grazing, the River Sherbourne for water and mill power — and prospered from trade, particularly wool production. Royal charters had granted Coventry extensive privileges, including the right to export merchandise overseas, freedom from certain tolls and both city and county status. The sword was one of those privileges.

By the 14th century, Coventry was the fourth largest city in England. It was rich in natural resources — timber, stone, arable land, pastures for grazing, the River Sherbourne for water and mill power — and prospered from trade, particularly wool production. Royal charters had granted Coventry extensive privileges, including the right to export merchandise overseas, freedom from certain tolls and both city and county status. The sword was one of those privileges.

Coventry had supported Lancastrian kings Henry V and Henry VI with troops and money. It became a de facto capital when Henry VI and his queen consort Margaret of Anjou moved the royal court there in the 1450s and parliament was called there several times between 1456 and 1460. Henry and Margaret even processed with the Coventry civic sword in front of them. After the defeat of Henry VI at the Battle of Northampton in 1460, the city made peace with the new Yorkist King Edward IV, but it wouldn’t last. The Earl of Warwick, formerly allied with Edward, turned coat and made an alliance with Margaret of Anjou. He occupied Coventry with 3,000 soldiers in March 1471. Edward showed up at the city’s massive defensive walls with his army demanding entry and was denied.

After Warwick’s forces were routed and the Earl killed at the Battle of Barnet on April 14th, Edward retaliated against Coventry by withdrawing many of its privileges, including county status, and confiscating its civic sword. The fate of the sword was unknown until it was rediscovered by accident in a rubbish heap in Whitechapel in 1897. It was first in the private collection of Sir Guy Laking, the first director of the London Museum. It later was acquired by Sir William and Lady Constance Burrell who gave it to the City of Glasgow in 1944.

The Coventry Sword today is not the same as the one Henry Knighton wrote about — it dates to around 1460 — but it is still a gladium ornatu aureo. While the blade was amputated, the hilt was in good condition considering its rough life. The ivory grip is intact, as is the bronze crossguard with gilded ornamentation of a Tudor Rose and Edward IV’s badge, the Sun in Splendour. The bronze pommel’s gilded decoration and silver side medallions also survived, to our good fortune. The silver medallions on the side of the pommel bear the Royal Arms and the arms of Coventry (elephant and castle), which is how we know which sword it is.

The Coventry Sword today is not the same as the one Henry Knighton wrote about — it dates to around 1460 — but it is still a gladium ornatu aureo. While the blade was amputated, the hilt was in good condition considering its rough life. The ivory grip is intact, as is the bronze crossguard with gilded ornamentation of a Tudor Rose and Edward IV’s badge, the Sun in Splendour. The bronze pommel’s gilded decoration and silver side medallions also survived, to our good fortune. The silver medallions on the side of the pommel bear the Royal Arms and the arms of Coventry (elephant and castle), which is how we know which sword it is.

The sword is on display at the Herbert Art Gallery & Museum until November 21st.

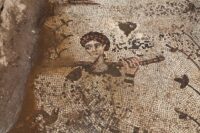

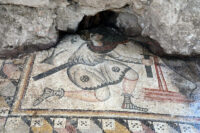

A large 4th century mosaic discovered in Gaziantep, southern Turkey, in 2019 when looting activity was reported at a private home has been removed in 98 pieces and transported to the Zeugma Mosaic Museum. The illegal excavation was reported in time to save a massive mosaic covering 1830 square feet, the entire courtyard of the property. It took two days to raise and transport every section of the mosaic to the museum.

A large 4th century mosaic discovered in Gaziantep, southern Turkey, in 2019 when looting activity was reported at a private home has been removed in 98 pieces and transported to the Zeugma Mosaic Museum. The illegal excavation was reported in time to save a massive mosaic covering 1830 square feet, the entire courtyard of the property. It took two days to raise and transport every section of the mosaic to the museum. The house was secured by the Provincial Directorate of Culture and Tourism and salvage efforts began in 2020. A thorough excavation revealed mosaics composed of white and multi-colored stone and glass tesserae. Panels depicting figures — a kneeling man carrying a sword, a goddess wearing a diadem, carrying a spear and holding the leash of a wild beast — and animals are bordered by geometric designs.

The house was secured by the Provincial Directorate of Culture and Tourism and salvage efforts began in 2020. A thorough excavation revealed mosaics composed of white and multi-colored stone and glass tesserae. Panels depicting figures — a kneeling man carrying a sword, a goddess wearing a diadem, carrying a spear and holding the leash of a wild beast — and animals are bordered by geometric designs.