Painting conservators working on the west wall of the choir in Sauherad Church in southeastern Norway have discovered that the ostensible 17th century “Demon Wall” discovered during conservation work in 1940 was not discovered by the conservators. It was made by them.

Painting conservators working on the west wall of the choir in Sauherad Church in southeastern Norway have discovered that the ostensible 17th century “Demon Wall” discovered during conservation work in 1940 was not discovered by the conservators. It was made by them.

The dense black line drawing of demons, animals, clerics, princesses, one drawing linked to the next, all interwoven together in minute detail, cover the full width and height of the wall from the arch 8.5 feet above the floor to the top of the ceiling. The figures in some parts of the drawing are so tiny they are invisible to the naked eye from the floor.

Built between 1150 and 1250, Sauherad Church was ravaged by fire in the mid-17th century and extensively rebuilt. An altarpiece depicting scenes from Revelation was made in 1663. Around 1700, frescoes were painted on the walls and ceilings by Lauritz Pettersen. By the end of the 1700s, the church was in a dilapidated state, but it was repaired and expanded in 1848 and today is known for its surviving frescoes.

Built between 1150 and 1250, Sauherad Church was ravaged by fire in the mid-17th century and extensively rebuilt. An altarpiece depicting scenes from Revelation was made in 1663. Around 1700, frescoes were painted on the walls and ceilings by Lauritz Pettersen. By the end of the 1700s, the church was in a dilapidated state, but it was repaired and expanded in 1848 and today is known for its surviving frescoes.

Gerhard Gotaas and his son Per Gotaas were employed by the Directorate for Cultural Heritage to restore the faded frescoes on the walls of Sauherad Church from 1935 to 1941. The demon wall came to light in August 1940. Conservator Gerhard Gotaas wrote to Henry Fett, head of the Norwegian Directorate for Cultural Heritage and an expert in medieval Norwegian church art, that they had uncovered “faces and figures of humans and animals” on the west wall of the choir.

The drawings, unique in the Norwegian archaeological record, attracted much attention at the time of the discovery. Demons and the devil make an appearance in Norwegian church art, but always as part of a larger traditional Christian composition emphasizing the redemptive power of God and Christ. The demon wall of Sauherad is all damnation and no salvation.

The drawings, unique in the Norwegian archaeological record, attracted much attention at the time of the discovery. Demons and the devil make an appearance in Norwegian church art, but always as part of a larger traditional Christian composition emphasizing the redemptive power of God and Christ. The demon wall of Sauherad is all damnation and no salvation.

Henry Fett wrote about the wall in glowing terms in his 1941 book A Village Church:

Here the devils of revelation, the demons of the time, the eerie powers of existence, with all its uncontrolled and fateful forces and eerie mask life are depicted – all this which Christ had declared war, we have on the west wall of the choir. In large swarms, demons and devils hover in space, herd upon herd – a whole air squadron, an insect swarm of demons, animal masks with human features. human masks with animal features, the animal in man unfolds in all sorts of fantastic bastard forms, spiritual complexes have taken shape. What a gallery of demonic face types!

Traces of older wall paintings beneath the density of demons date to the time of the altarpiece, so mid-17th century, and the demons were believed to have been added shortly thereafter. There was speculation that they might have been painted by the proverbial insane priest. Fett nominated Jens Christensen Slagelse, who worked at Sauherad Church from 1621 to 1641.

Curator Susanne Kaun and art historian Elisabeth Andersen set up scaffolding to examine the murals under magnification, UV light and raking light. They also and scoured the archives for information about the discovery and 1940 conservation.

Gotaa claimed in his correspondence that he had found incised drawings and color remnants, but Kaun and Andersen found no incisions at all, and the original faded color elements that were from 17th century featured zero demons. The Gotaas did it all themselves, and bamboozled everyone for decades.

“We suspected for a long time that a lot had been painted and added, but when we saw the extent of Gotaa’s hand – we could hardly believe it,” Andersen says.

“That a conservator himself has painted his own decor, and claims that it is something he has found, is contrary to all conservation principles – also in the 1940s,” Kaun adds.

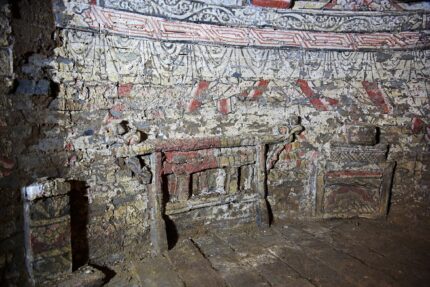

Archaeologists have discovered a cluster of 12 rare carved brick tombs dating to the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) in Jinan, capital of Eastern China’s Shandong province. Inscriptions found in the tomb indicate they all belong to one elite family, the Guo, who lived in the late Yuan Dynasty. Eleven of the 12 are elaborately frescoed and carved brick mural tombs. One is a stone chamber tomb.

Archaeologists have discovered a cluster of 12 rare carved brick tombs dating to the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) in Jinan, capital of Eastern China’s Shandong province. Inscriptions found in the tomb indicate they all belong to one elite family, the Guo, who lived in the late Yuan Dynasty. Eleven of the 12 are elaborately frescoed and carved brick mural tombs. One is a stone chamber tomb. The 12 Yuan tombs were part of a group of 35 tombs of different ages unearthed at the site since excavations began in April. It’s the largest group of Yuan brick mural tombs discovered in Shandong.

The 12 Yuan tombs were part of a group of 35 tombs of different ages unearthed at the site since excavations began in April. It’s the largest group of Yuan brick mural tombs discovered in Shandong.