Archaeologists have discovered a unique Copper Age burial containing 140 pieces of amber jewelry on the shores of Lake Onega in the Republic of Karelia, northwestern Russia. The grave dates to around 3400 B.C., and no other burials from this period have been found in Karelia or its neighboring regions in northwestern Russia containing anything close to this much amber.

Archaeologists have discovered a unique Copper Age burial containing 140 pieces of amber jewelry on the shores of Lake Onega in the Republic of Karelia, northwestern Russia. The grave dates to around 3400 B.C., and no other burials from this period have been found in Karelia or its neighboring regions in northwestern Russia containing anything close to this much amber.

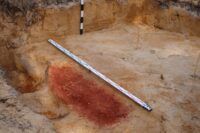

A team from Petrozavodsk State University (PetrSU) made the find while surveying sites of prehistoric settlements on the western shore of the lake. The grave is a narrow oval pit that was covered in red ochre paint for ritual reasons. Inside the grave an assortment of pendants, buttons and discs made of Baltic amber were unearthed. Some of these types are so rare they were only known from single discoveries in the Eastern Baltic before now, and those were found in ancient settlements, not in a funerary context.

A team from Petrozavodsk State University (PetrSU) made the find while surveying sites of prehistoric settlements on the western shore of the lake. The grave is a narrow oval pit that was covered in red ochre paint for ritual reasons. Inside the grave an assortment of pendants, buttons and discs made of Baltic amber were unearthed. Some of these types are so rare they were only known from single discoveries in the Eastern Baltic before now, and those were found in ancient settlements, not in a funerary context.

Along the edges of the burial pit, amber ornaments were deposited thickly in two tiers. In the center, they were face down in rows. They had originally been stitched to a leather cape draped over the body. When the leather rotted away, the amber pieces remained in place.

Small flint chips flaked off in the production of tools were placed on the body. Archaeologists believe the lithic deposits were meant to symbolize weapons like arrowheads and knives. There is no local source of flint in Karelia and the amber was also non-local, coming from the Eastern Baltic region, so these materials in the grave can only have been acquired through trade networks.

No other graves have been found at the site, which is another way in which this burial is unique.

Since the Mesolithic era, in the forest belt of Europe, ancient people buried the dead in ancestral cemeteries. The burial with rich grave goods found in the vicinity of Petrozavodsk is a single one. In addition, some of the discovered amber jewelry found in the grave had not been found in Eastern Europe before. It is possible that a trader from the Eastern Baltic States was buried in the grave, who arrived on the western shore of Lake Onega to acquire (in exchange for amber) slate chopping tools. Workshops for the production of slate axes and adzes are currently being investigated by the university expedition just next to the burial site.

The burial discovered by the PetrSU expedition testifies to the formation of the so-called “prestigious” primitive economy among primitive people living in Northern Europe, in which jewelry and especially valuable tools were made to maintain the high social status of their owners. Various jewelry and other prestigious items accumulated by some noble hunters are currently found by archaeologists usually in burials.

The “amber” burial discovered by the expedition of Petrozavodsk University testifies to the strong ties of the ancient population of Karelia with the tribes that lived on the southern coast of the Baltic Sea.