One of three men who tried to steal a huge hoard of Roman gold coins from the Rhineland State Museum in Trier in 2019 has been sentenced to 2.5 to 3.5 years in prison for the bungled robbery. The trio broke into the museum ON MY BIRTHDAY (rude and disrespectful) by climbing scaffolding and prying open a window. They sledgehammered a door down and then two of them entered the gallery while the third stood guard. They were not able to break through the reinforced glass display case. When the alarm went off and the police arrived, the thieves fled empty-handed.

One of three men who tried to steal a huge hoard of Roman gold coins from the Rhineland State Museum in Trier in 2019 has been sentenced to 2.5 to 3.5 years in prison for the bungled robbery. The trio broke into the museum ON MY BIRTHDAY (rude and disrespectful) by climbing scaffolding and prying open a window. They sledgehammered a door down and then two of them entered the gallery while the third stood guard. They were not able to break through the reinforced glass display case. When the alarm went off and the police arrived, the thieves fled empty-handed.

A 28-year-old Dutch man was later identified from DNA found on a gym bag at the crime scene. He was deported to Germany in late 2020, charged and confessed to having been an accomplice, although he denied having been one of the guys who made it inside and tried to break the display case. His confession and claim to have been the guard only is what got him the light sentence. The other two are still at large.

The hoard of 2,518 aurei was discovered September 9th, 1993, when an excavator dug up a broken bronze vessel full of soil and gold coins during construction of a hospital parking deck. That’s the coin count now, anyway. The hoard has had to deal with would-be looters before. News spread locally and treasure hunters descended on the find with metal detectors pocketing an unknown number of scattered coins before archaeologists could get to the site. The prospect of legal repercussions and difficulties converting ancient Roman coins into easy cash spurred many of the looters to return the ill-gotten coins to the Rheinisches Landesmuseum, although an estimated 100-200 are still dispersed. One of the looters is known to have paid his beer tab with them that night.

The hoard of 2,518 aurei was discovered September 9th, 1993, when an excavator dug up a broken bronze vessel full of soil and gold coins during construction of a hospital parking deck. That’s the coin count now, anyway. The hoard has had to deal with would-be looters before. News spread locally and treasure hunters descended on the find with metal detectors pocketing an unknown number of scattered coins before archaeologists could get to the site. The prospect of legal repercussions and difficulties converting ancient Roman coins into easy cash spurred many of the looters to return the ill-gotten coins to the Rheinisches Landesmuseum, although an estimated 100-200 are still dispersed. One of the looters is known to have paid his beer tab with them that night.

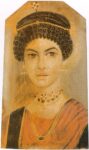

Archaeologists spent 20 years fully documenting and cataloging the treasure. They found coins minted over the course of more than a century. The aurei bear portraits of 27 emperors and a dozen empresses and imperial family members. More than 80 previously unknown coin types were found in the Trier hoard, including a portrait of Didius Julianus who ruled Rome for three months (March-June 193) after literally buying the throne when the Praetorian Guard, who had assassinated Pertinax, auctioned it off to the highest bidder.

The oldest dates to the reign of Nero in 63/64 A.D., the youngest to that of Septimius Severus in 193-196 A.D. Given the end-date, archaeologists believe the hoard was buried shortly after that outside date. Trier, Augusta Treverorum in antiquity, was the main city of the province of Gallia Belgica. [Fun fact: Didius Julianus was governor of Gallia Belgica 20 years before his face was stamped on a gold coin during his nine weeks of glory.] With its population, prosperity and political importance, it was in the cross-hairs of plenty of Germanic invasion waves, plagues and the emperor-usurper-counter-usurper rondelets. The monumental Porta Nigra gate and the defensive walls of the town were built between 180 and 200 A.D. during the reign of Emperor Marcus Aurelius.

The oldest dates to the reign of Nero in 63/64 A.D., the youngest to that of Septimius Severus in 193-196 A.D. Given the end-date, archaeologists believe the hoard was buried shortly after that outside date. Trier, Augusta Treverorum in antiquity, was the main city of the province of Gallia Belgica. [Fun fact: Didius Julianus was governor of Gallia Belgica 20 years before his face was stamped on a gold coin during his nine weeks of glory.] With its population, prosperity and political importance, it was in the cross-hairs of plenty of Germanic invasion waves, plagues and the emperor-usurper-counter-usurper rondelets. The monumental Porta Nigra gate and the defensive walls of the town were built between 180 and 200 A.D. during the reign of Emperor Marcus Aurelius.

The total weight of the hoard is 18.5 kilos (41 lbs). In buying power at the time, this much gold would have paid the annual salaries of 130 Roman soldiers, and it was almost certainly not an individual’s personal wealth, but rather an official treasury, meticulously administered and added to over time.

The largest preserved Roman Imperial gold hoard ever discovered, the Trier Gold Hoard is the centerpiece of the Rheinisches Landesmuseum’s 12,000-coin collection. Since the robbery attempt, it has been out of public view while security systems are reviewed.

An alignment of 13 menhirs has been discovered still standing upright in Saint-Léonard in the canton of Valais, southwestern Switzerland. The rare stones were found during an excavation in advance of real estate development.

An alignment of 13 menhirs has been discovered still standing upright in Saint-Léonard in the canton of Valais, southwestern Switzerland. The rare stones were found during an excavation in advance of real estate development. B.C.). The area was very active in the Neolithic era and one of the most important prehistoric sites in Europe, featuring numerous Late Neolithic dolmens (collective burials), engraved stelae and standing stones, is less than four miles west of Saint-Léonard in the town of Sion.

B.C.). The area was very active in the Neolithic era and one of the most important prehistoric sites in Europe, featuring numerous Late Neolithic dolmens (collective burials), engraved stelae and standing stones, is less than four miles west of Saint-Léonard in the town of Sion. The excavation is almost complete. When it’s done, the plan is to remove the stones and transport them elsewhere for additional studies. Canton and city authorities will determine at that point what to do with the menhirs. This sounds … suboptimal. That they are standing in position is hugely significant, archaeologically speaking. Destroying that original context on the pretext of studying the deracinated stones in “the best conditions” strikes me as a decision grounded more in cleaning the way for construction than in any archaeological good judgement.

The excavation is almost complete. When it’s done, the plan is to remove the stones and transport them elsewhere for additional studies. Canton and city authorities will determine at that point what to do with the menhirs. This sounds … suboptimal. That they are standing in position is hugely significant, archaeologically speaking. Destroying that original context on the pretext of studying the deracinated stones in “the best conditions” strikes me as a decision grounded more in cleaning the way for construction than in any archaeological good judgement.