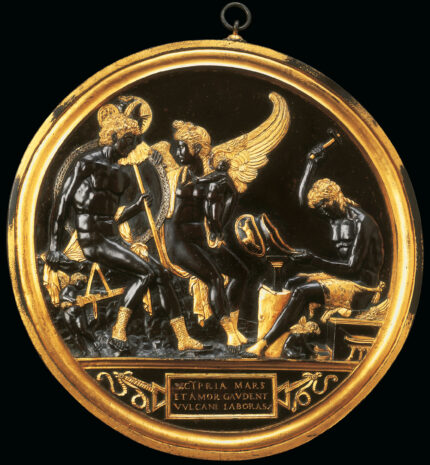

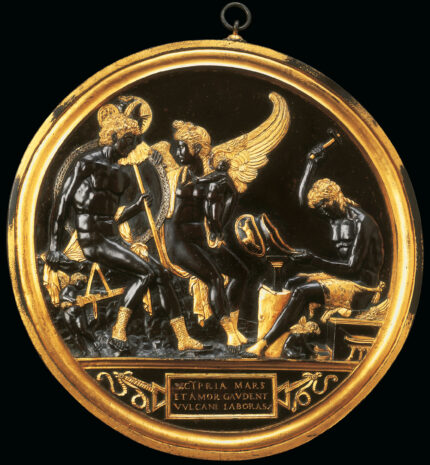

The Metropolitan Museum of Art has at long last acquired an exceptional Renaissance parcel-gilt bronze roundel 18 years after it first tried and failed to buy it at auction. At 16.5 inches in diameter, rimmed and embellished with gilded accents and silver inlay, it is the largest bronze roundel known from the Renaissance, and one of the most if not the most technically sophisticated, which is why the Met was more than willing to pay 27 million dollars and wait a year to not let this masterpiece slip through its fingers again.

It depicts Venus and her lover Mars flirting while her husband Vulcan labors at the forge. Venus sits in the center with Cupid on her lap driving his arrow into her breast. She has wings, the right one outstretched and fully visible, the left mostly hidden behind Mars’ shield. Mars is armed with a sword and scabbard. Vulcan is making a helmet embossed with a horse, his hammer raised mid-strike.

In the exergue below the scene is a Latin inscription reading “CYPRIA MARS ET AMOR GAVDENT VVLCANE LABORAS,” meaning “Venus, Mars and Cupid enjoy themselves while Vulcan works.” This was a popular motif in the art of northern Italy in the late 15th, early 16th centuries.

The exceptional quality of the rendering from the masks on Venus’ sandals, Mars’ decorated scabbard, even the wrinkles on Vulcan’s face delicately gilded for emphasis indicate this work was cast by a master goldsmith. Metallurgic analysis of the bronze alloy found it has an unusually high copper content comparable to Renaissance medals now in the National Gallery in Washington.

There is no definitive information about its origins and ownership history. The roundel first burst on the scene in 2003 at a Christie’s auction in London. Appraisers discovered it, unpublished and unrecognized, in an estate belonging to the heirs of George Treby III, a lawyer and MP in the first half of the 18th century. Treby was an avid collector of art and antiquities and is known to have Grand Toured in Rome in 1746. There is no documentation of his acquisition of the roundel, but given that his descendants had it for centuries, he is almost certainly the source.

The 2003 sellers had no idea it was a Renaissance piece. They assumed it was of relatively late manufacture. Christie’s experts recognized it as having been made in the late 15th century for the Gonzaga court in Mantua, Italy. There are no other versions of it known to exist, nor any roundels of this size crafted by this hand. The only cognate is a plaster relief from the Bardini Collection in Florence, and its attribution is uncertain.

Christie’s leading candidate for the master craftsman who made the roundel was Gian Marco Cavalli, known from the documentary record as having made bronzes for the Gonzaga family, but there are no works firmly attributed to him. His details fit the bill, though. He was a goldsmith, he did a commission of four silver roundels with the signs of the zodiac for the Gonzaga. His last name may even appear on the roundel in disguise. “Cavalli” means horses, and he called himself “Cavallino” in one letter, so that disproportionately large rearing horse on the helmet Vulcan is hammering out may be a sort of secret signature.

Even with an unknown maker, the roundel roused enormous interest at the 2003 auction. The Met was an active bidder, but ultimately lost out to a private collector who bought it for £6.9 million, setting a new world record for a Renaissance bronze. The buyer’s family sold the roundel to a UK art dealer in 2019 for an undisclosed amount. The dealer gave the Met a second bite at the apple, and this time money was evidently no object because the museum dropped £17 million plus £3.4 million VAT) to buy the bronze, contingent on the granting of an export license.

The UK Ministry of Culture imposed a temporary export ban to give a British institution a chance to acquire the piece for the purchase price including VAT. When nobody could be found with such deep pockets by the end of 2021, the UK granted the export license.

“The bronze roundel is an absolute masterpiece, standing apart for its historical significance, artistic virtuosity, and unique composition,” said Max Hollein, the Museum’s Marina Kellen French Director. “It is a truly transformational acquisition for The Met’s collection of Italian Renaissance sculpture. We look forward to further studying and displaying this magnificent work, one that establishes Cavalli as one of the ingenious creators of the Gonzaga court style.”

Cavalli (born about 1454, died after 1508) collaborated for over 30 years with Andrea Mantegna (1430/31–1506), the principal painter to the Gonzaga court in Mantua, and with Antico (ca. 1460–1528), the Gonzaga family’s principal sculptor. Yet the attribution of works to Cavalli remained challenging until the discovery of the roundel in a British country house in 2003. The roundel may have been made for Isabella d’Este, Marchioness of Mantua (1474–1539), the most important woman patron of the Italian Renaissance.

Dr. Sarah E. Lawrence, the Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Curator in Charge of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts, stated, “While The Met is rich in paintings and prints by Mantegna, and holds the largest collection of Antico’s gilt and silvered bronze sculptures outside Europe, there was no equivalent example in bronze relief in our collection. With this exciting acquisition, The Met is now one of the only museums in the world that can illustrate the fundamental collaboration between Mantegna, Antico, and Cavalli under the patronage of Isabella d’Este.” Denise Allen, Curator in the Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts, added: “The Mantuan roundel’s sumptuous gilding, meticulously inlaid silvering, and masterfully varied chasing identify the roundel as a masterpiece in which Cavalli expressed his superlative abilities as a goldsmith and sculptor.”