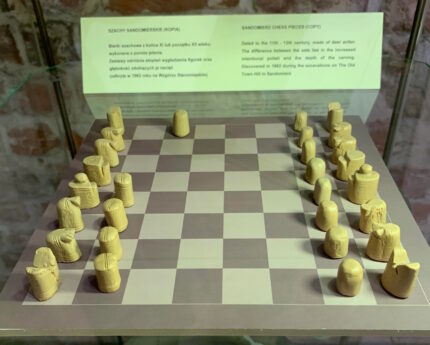

The Sandomierz chessmen, a chess set from the 12th or 13th century discovered at Sandomierz Castle in southeastern Poland, were made from the bones of horses, cows and deer, DNA analysis has revealed. They were originally believed to have been carved from deer antlers, or the bones of an exotic large animal like an elephant.

The Sandomierz chessmen, a chess set from the 12th or 13th century discovered at Sandomierz Castle in southeastern Poland, were made from the bones of horses, cows and deer, DNA analysis has revealed. They were originally believed to have been carved from deer antlers, or the bones of an exotic large animal like an elephant.

University of Warsaw researchers were able to drill small samples from the underside of the pieces and extract an almost complete mitochondrial genome identifying the more elaborately decorated side of the set as having been made from horse bone while its opponents were made from cow bones. One pawn (believed to have been carved later than the others) was made from the bone of a red deer.

The chessmen were discovered in 1962 during archaeological excavations of what had been the heart of the medieval city. Only about 50 medieval chess pieces have been found in Poland, but most of them were individual finds. The Sandomierz chessmen, on the other hand, compose a practically complete matched set with only three missing pieces.

The pieces were carved by hand, ground down and polished to a gloss. It’s possible one side was originally dyed or painted another color, but all traces of that are gone so today they’re both just plain bone-colored. Some of them were created in twos, connected by a base that was then cut apart to separate the individual pieces. Carved in the abstract style typical of medieval Islamic chess sets in keeping with the religious prohibition against realistic depiction of human figures, they were embellished with incised parallel lines and dot-and-circle markings carved using a compass.

The pieces were carved by hand, ground down and polished to a gloss. It’s possible one side was originally dyed or painted another color, but all traces of that are gone so today they’re both just plain bone-colored. Some of them were created in twos, connected by a base that was then cut apart to separate the individual pieces. Carved in the abstract style typical of medieval Islamic chess sets in keeping with the religious prohibition against realistic depiction of human figures, they were embellished with incised parallel lines and dot-and-circle markings carved using a compass.

The Gothic-style Sandomierz Castle was built by King Casimir III the Great in the 14th century. All that remains of that castle today are some of the foundations of the tower. (The rest was blown up in the 17th century by Swedish troops during the Deluge.) It was preceded by an earlier stronghold dating to the 10th century. In the 12th century, the castle was the seat of Henry I of Sandomierz, Piast dynasty prince and son of Boleslaus III, ruler of Poland. Henry led the Polish troops in the Second Crusade (1147) and returned again to the Holy Land in the 1150s.

At the time of the find, archaeologists believe that Henry may have brought the chessmen back from his travels in the Middle East, but the DNA evidence that they were carved from the bones of native European animals opens other possibilities, even as it cannot conclusively determine where they were manufactured. For example, they could have been brought to the city by Dominican friars from Italy — the find site was next to the Dominican church of St. Joseph’s, founded in 1226 — or via the trade routes connecting Kiev to Western Europe. They could even be locally produced. The incised lines and compass decorations have been found on other early Polish antler and bone products.