The tomb of Caecilia Metella, the turret-shaped funerary monument on the Via Appia Antica outside the ancient walls of Rome, was built out of concrete, brick and travertine between 30 and 10 B.C., a time when Roman architecture saw major advances in concrete construction. The circular concrete tomb was faced with blocks of travertine and built on a square foundation of concrete with volcanic stone aggregrate. Inside is a conical burial chamber with an oculus opening in the ceiling. The sepulchral corridor was constructed of brick-faced concrete that is one of the first examples in Rome, built to the highest possible standards of the time.

The tomb of Caecilia Metella, the turret-shaped funerary monument on the Via Appia Antica outside the ancient walls of Rome, was built out of concrete, brick and travertine between 30 and 10 B.C., a time when Roman architecture saw major advances in concrete construction. The circular concrete tomb was faced with blocks of travertine and built on a square foundation of concrete with volcanic stone aggregrate. Inside is a conical burial chamber with an oculus opening in the ceiling. The sepulchral corridor was constructed of brick-faced concrete that is one of the first examples in Rome, built to the highest possible standards of the time.

The tomb is located on the northern tip of the Capo di Bove lava flow; its lower chamber was dug through the tephra deposited hundreds and thousands of years ago in the eruption of the Alban Hills volcano. The same volcano also deposited tephra in a lava flow, the Pozzolane Rosse, less than a half mile away northwest of the tomb.

The builders of the Tomb of Caecilia Metella sourced their aggregate from both fields, using the Capo di Bove lava for the outer structure’s concrete, brick mortar and interior concrete. The sepulchral corridor (the wettest part of the tomb, exposed to rainwater falling through the oculus as well as ground water penetration) used the tephra from the Pozzolane Rosse flow, the same aggregate employed in the construction of the walls of the Markets of Trajan 120 years later. They too are still standing.

The builders of the Tomb of Caecilia Metella sourced their aggregate from both fields, using the Capo di Bove lava for the outer structure’s concrete, brick mortar and interior concrete. The sepulchral corridor (the wettest part of the tomb, exposed to rainwater falling through the oculus as well as ground water penetration) used the tephra from the Pozzolane Rosse flow, the same aggregate employed in the construction of the walls of the Markets of Trajan 120 years later. They too are still standing.

Roman concrete construction like this tomb, bridge piers and breakwaters has shown itself uniquely capable of withstanding thousands of years of water exposure, even submersion, whereas modern concrete, made with cement binders that Roman concrete does not have, cracks and crumbles comparatively speedily under pressure from water. Modern marine concrete has an expected lifespan of just 50 years.

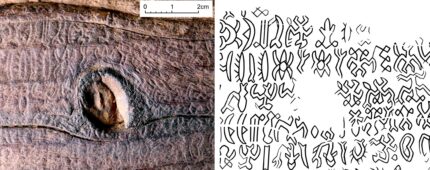

A new study looks at mortar samples taken from the sepulchral corridor of the Tomb of Caecilia Metella to learn more about the mineral structure of the concrete hoping to shed light on its extraordinary longevity.

In previous analysis of the Markets of Trajan mortar, Jackson, Tamura and their colleagues explored the “glue” of the mortar, a building block called the C-A-S-H binding phase (calcium-aluminum-silicate-hydrate), along with a mineral called strätlingite. The strätlingite crystals block the propagation of microcracks in the mortar, preventing them from linking together and fracturing the concrete structure.

But the tephra the Romans used for the Caecilia Metella mortar was more abundant in potassium-rich leucite. Centuries of rainwater and groundwater percolating through the tomb’s walls dissolved the leucite and released the potassium into the mortar. In modern concrete, such a flood of potassium would create expansive gels that would cause microcracking and eventual spalling and deterioration of the structure.

In the tomb, however, the potassium dissolved and reconfigured the C-A-S-H binding phase. Seymour says that X-ray microdiffraction and Raman spectroscopy techniques allowed them to explore how the mortar had changed. “We saw C-A-S-H domains that were intact after 2,050 years and some that were splitting, wispy or otherwise different in morphology,” she says. X-ray microdiffraction, in particular, allowed an analysis of the wispy domains down to their atomic structure. “We see that the wispy domains are taking on a nano-crystalline nature,” she says.

The remodeled domains “evidently create robust components of cohesion in the concrete,” says Jackson. In these structures, unlike in the Markets of Trajan, there’s much less strätlingite formed. […]

Admir Masic, associate professor of civil and environmental engineering at MIT, says that the interface between the aggregates and the mortar of any concrete is fundamental to the structure’s durability. In modern concrete, he says, the alkali-silica reactions that form expansive gels may compromise the interfaces of even the most hardened concrete.

“It turns out that the interfacial zones in the ancient Roman concrete of the tomb of Caecilia Metella are constantly evolving through long-term remodeling,” he says. “These remodeling processes reinforce interfacial zones and potentially contribute to improved mechanical performance and resistance to failure of the ancient material.”

The study is part a U.S. Department of Energy ARPA-e project that hopes to use ancient Roman know-how to create more durable and energy-efficient concrete. It has been published in the Journal of the American Ceramic Society and can be read in its entirety here.