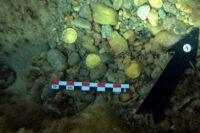

A group of 53 Roman gold coins have been discovered on the seabed off the coast of Xàbia in Alicante, southeastern Spain. They are gold solidi ranging in date from the late 4th to the early 5th century, and are in such excellent condition that all the coins but one could be identified. There are three solidi from the reign of Emperor Valentinian I, seven from Valentinian II, 15 from Theodosius I, 17 from Arcadius and 10 from Honorius.

The coins were discovered on the sea bottom next to Portitxol island, a popular destination for sport divers because of the rich marine life that inhabits its seaweed meadows of its rocky bed. Even so, it managed to hide dozens of Roman gold coins for 1,500 years until freedivers Luis Lens and César Gimeno spotted eight flashes of light on the seafloor. At first they thought they were modern ten cent pieces, or maybe mother-of-pearl shells gleaming in the water. They picked up two of them.

The coins were discovered on the sea bottom next to Portitxol island, a popular destination for sport divers because of the rich marine life that inhabits its seaweed meadows of its rocky bed. Even so, it managed to hide dozens of Roman gold coins for 1,500 years until freedivers Luis Lens and César Gimeno spotted eight flashes of light on the seafloor. At first they thought they were modern ten cent pieces, or maybe mother-of-pearl shells gleaming in the water. They picked up two of them.

When they returned to the boat, they saw that they were ancient gold coins bearing identical profiles of a Roman emperor. They immediately alerted city officials to their discovery and led marine archaeologists to the find site. Over several dives, the team of archaeologists recovered the 53 gold coins, three copper nails and fragments of lead that may have been fittings on a chest.

This is one of the largest sets of Roman gold coins found in Spain and Europe, as stated by Professor in Ancient History Jaime Molina and University of Alicante team leader of the underwater archaeologists working on the wreck. He also reported that this is an exceptional archaeological and historical find, since it can offer a multitude of new information to understand the final phase of the fall of the Western Roman Empire. The historians point to the possibility that the coins may have been intentionally hidden, in a context of looting such as those perpetrated by the Alans in the area at that time.

Therefore, the find would serve to illustrate a historical moment of extreme insecurity with the violent arrival of the barbarian peoples (Suevi, Vandals and Alans) in Hispania and the final end of the Roman Empire in the Iberian Peninsula from 409 A.D.

The coins are now being conserved and studied before going on display at the Soler Blasco Archaeological and Ethnographic Museum in Xàbia, conditioned on the acquisition of an armored glass case equipped with sensors to secure the valuable (and easily meltable) artifacts. Funding has already been secured to return to the find site for a more thorough excavation.