A small silver ring and shield that once identified a bird of prey used for hunting by Henry Frederick Stuart, Prince of Wales, eldest son of King James I, was discovered by metal detectorists Jason Jackson and Alan Daynes in the east Norfolk town of Cley-next-the-Sea last year. While historic hawking vervels, as these rings are called, are not uncommon in the area — the Castle Museum in Norwich has more vervels in its permanent collection than the British Museum — royal ones are rare. One belonging to King Henry VIII’s brother-in-law and standard bearer Charles Brandon, first duke of Suffolk, was found in December of last year but he was known to have hunted in the area many times. There are no records at all indicating Henry Frederick ever went to Norfolk at all so that makes this find even more exciting.

A small silver ring and shield that once identified a bird of prey used for hunting by Henry Frederick Stuart, Prince of Wales, eldest son of King James I, was discovered by metal detectorists Jason Jackson and Alan Daynes in the east Norfolk town of Cley-next-the-Sea last year. While historic hawking vervels, as these rings are called, are not uncommon in the area — the Castle Museum in Norwich has more vervels in its permanent collection than the British Museum — royal ones are rare. One belonging to King Henry VIII’s brother-in-law and standard bearer Charles Brandon, first duke of Suffolk, was found in December of last year but he was known to have hunted in the area many times. There are no records at all indicating Henry Frederick ever went to Norfolk at all so that makes this find even more exciting.

The vervel was declared treasure at a coroner’s inquest last year, after which experts at the BM assessed its market value at £6,000. Thanks to a £2,400 grant from the Victoria & Albert Purchase Grant Fund and a £2,000 grant from the Art Fund, the Castle Museum was able to acquire the rare piece. It will go on display along with the other vervels in the museum’s collection next year (May 24th through September 14th) in The Wonder of Birds, an exhibition exploring avian topics like the birth of ornithology, birds in art, birds as symbols of status, birds in their natural environment and much more.

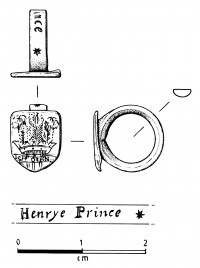

It’s a wee piece, with the ring just 10.5 millimeters in diameter and the shield 10 x 8 millimeters in size. It weighs 1.37 grams. Much like avian leg bands today, vervels had to be small and light so as not to be a burden on the creature in flight. They were attached to the jesses, thin leather straps tied to the bird’s legs as tethers to make the birds easier to handle on the arm, and again like modern avian leg bands, served to identify the bird should it be lost during the hunt or in training.

That’s how we know the ring belonged to one of Henry’s hawking birds: the prince’s name and symbol are on it. The outside of the band is engraved “Henrye Prince” and the shield is engraved with the heraldic badge of the Prince of Wales: three ostrich plumes encircled by a coronet on top of a ribbon bearing the phrase “ICH DIEN,” a contraction of “I serve” in German. Henry was only Prince of Wales for two years, so we know the vervel was made between 1610 and 1612.

That’s how we know the ring belonged to one of Henry’s hawking birds: the prince’s name and symbol are on it. The outside of the band is engraved “Henrye Prince” and the shield is engraved with the heraldic badge of the Prince of Wales: three ostrich plumes encircled by a coronet on top of a ribbon bearing the phrase “ICH DIEN,” a contraction of “I serve” in German. Henry was only Prince of Wales for two years, so we know the vervel was made between 1610 and 1612.

How it wound up where it was found is not so clear. Cley-next-the-Sea is a sleepy seaside village of 376 souls today, but in Henry’s day it was one of England’s busiest port cities thanks its location on the wide and deep estuary of the tidal River Glaven *. (Later in the 17th century, the estuary gradually began to silt over when local landowners attempted to reclaim marshy land by building embankments along the river. By the end of the next century, the River Glaven was no longer tidal and there was no more port.) Henry could have been in the area personally — just because no record of the Prince of Wales ever visiting Norfolk has survived doesn’t mean it didn’t happen — or one of his birds may have been there without him, either because it flew away never to return (entire breeding populations have been founded by escaped falconer’s birds) or because it was being trained for him by someone local.

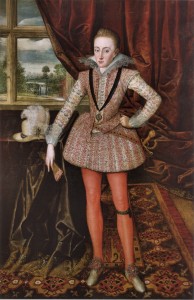

Henry was an accomplished hawker and sportsman in general, despite his young age. His athleticism was one of his most praised features, along with his intelligence, reserve, judicious involvement in politics and public works and his moral rectitude (he made people who cussed in his presence put money in an alms box dedicated to the purpose, a 17th century swear jar). Falconry, the Sport of Kings as it’s still known today even though no kings do it anymore, was seen as a particularly proper pursuit for the heir to the throne as it was thought to teach leadership in battle.

Henry was an accomplished hawker and sportsman in general, despite his young age. His athleticism was one of his most praised features, along with his intelligence, reserve, judicious involvement in politics and public works and his moral rectitude (he made people who cussed in his presence put money in an alms box dedicated to the purpose, a 17th century swear jar). Falconry, the Sport of Kings as it’s still known today even though no kings do it anymore, was seen as a particularly proper pursuit for the heir to the throne as it was thought to teach leadership in battle.

Henry never got to put those leadership skills to the test on the throne. He died of typhoid fever in 1612 when he was just 18 years old. The country went into deep mourning for the prince. His father was unpopular and it was Henry who was seen as the unifying figure who could truly bring Scotland and England together. So many people wanted to pay their respects that Henry’s body lay in state for four weeks and his funeral procession was a mile long. After his death, his younger brother Charles, then 12 years old, became heir. He was not so roundly beloved. That would matter a great deal since he became King Charles I whose power struggles with Parliament became Civil War and whose head became separated from his neck on January 30th, 1649.

*(![]() )

)

I think that “prey bird” in the first sentence should be “bird of prey.” A prey bird is one which is preyed upon e.g. pigeons and ducks.

Also, I would bet a beer that the kings of Saudi Arabia and Jordan still go hawking.

You’re definitely right on the former point, and I’d probably be out a beer if I took you up on the latter. Thank you!

Thank you very much for the information very helpful. I have one not the same but same but very similar in size and shape and it’s silver.