On Wednesday the Provincial Court of La Coruña convicted former electrician José Manuel Fernández Castiñeiras of stealing the Codex Calixtinus, an invaluable 12th century manuscript that contains the first travel guide for pilgrims on their way to the shrine of St. James in the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela. For the theft of the codex, ongoing burglaries of cash and other items and money laundering, Castiñeiras was sentenced to 10 years in prison (three for the codex, five for the burglaries, two for the laundering) and a 268,000 euro ($304,000) fine. His wife Remedios Nieto was sentenced to six months for money laundering and got her own 268,000 euro fine because she had to have known her husband’s wealth was ill-gotten. His son Jesus Fernández Nieto was acquitted as the court considered him a patsy used by his father who bought two apartments in his son’s name to launder some of the stolen money.

On Wednesday the Provincial Court of La Coruña convicted former electrician José Manuel Fernández Castiñeiras of stealing the Codex Calixtinus, an invaluable 12th century manuscript that contains the first travel guide for pilgrims on their way to the shrine of St. James in the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela. For the theft of the codex, ongoing burglaries of cash and other items and money laundering, Castiñeiras was sentenced to 10 years in prison (three for the codex, five for the burglaries, two for the laundering) and a 268,000 euro ($304,000) fine. His wife Remedios Nieto was sentenced to six months for money laundering and got her own 268,000 euro fine because she had to have known her husband’s wealth was ill-gotten. His son Jesus Fernández Nieto was acquitted as the court considered him a patsy used by his father who bought two apartments in his son’s name to launder some of the stolen money.

The court concluded that the electrician had taken keys to, among other locations, the office of the Dean and of the administrator, and used them to gain access to the Cathedral safe that regularly held large quantities of cash from sales of tickets to the Cathedral museum and roof, rent from Church properties and donations of the faithful. The total amount Castiñeiras stole in cash alone is 2.4 million euros ($2,735,000) in currency from 59 countries.

Defense counsel Carmen Ventoso tried the “this whole courtroom is out of order” defense, calling the trial a “procedural Guantanamo” in which the defendants’ rights had been trampled from before they were even on trial. She claimed police had broken into the house and installed monitoring devices a month before the arrest, that the official police search exceeded the parameters of the warrant, that the first interview in which Castiñeiras admitted he had stolen the Codex at 12:00 AM on July 4th, 2011, was full of errors and invalidated by the interrogator’s hardball tactics (“suggestive,” “argumentative” and “repetitive” questioning verging on duress), and that the Cathedral’s security camera footage showing the defendant shoving stacks o’ cash into his pockets was altered after the fact to incriminate her client. She wanted the search thrown out and all the evidence gathered as a result of it.

Defense counsel Carmen Ventoso tried the “this whole courtroom is out of order” defense, calling the trial a “procedural Guantanamo” in which the defendants’ rights had been trampled from before they were even on trial. She claimed police had broken into the house and installed monitoring devices a month before the arrest, that the official police search exceeded the parameters of the warrant, that the first interview in which Castiñeiras admitted he had stolen the Codex at 12:00 AM on July 4th, 2011, was full of errors and invalidated by the interrogator’s hardball tactics (“suggestive,” “argumentative” and “repetitive” questioning verging on duress), and that the Cathedral’s security camera footage showing the defendant shoving stacks o’ cash into his pockets was altered after the fact to incriminate her client. She wanted the search thrown out and all the evidence gathered as a result of it.

The court, unsurprisingly, was not persuaded by this argument or by Ventoso’s repeated imprecations against Judge José Antonio Vázquez Taín who, according to her, is a sterling example of “what shouldn’t be done.” The judge didn’t buy her next defense — that Castiñeiras had OCD and was a hoarder — either, on account of he somehow managed to overcome this compulsion just fine when he invested his filthy lucre in property.

On the stand last month, the first time he spoke publically about the theft, Castiñeiras admitted he had “probably” stolen all that cash (different news stories put the amount at anywhere from 1.7 to 2.4 million euros) from the Cathedral safe before he had a stroke in 2004, but he stopped keeping his accounts after the stroke and couldn’t remember if he kept stealing. When the magistrate asked him if he had stolen any other artworks or valuables from the church (a number of antiquities were also found in his home), the defendant replied that he woke up every day at 6:00 AM to work hard for the Cathedral. Because apparently early mornings and work entitle you to stuff millions in cash, art, church documents and whatever else into your pockets, seems to be the implication.

That fits with the disgruntled employee theory of the crime. He was let go in 2011, officially due to restructuring, but possibly because he was suspected of theft. That can’t have been the source of his cleptorage, however. He may have stolen the Codex Calixtinus in July of 2011 out of pique, but he’d been making off with huge fistfuls of cash regularly for something like a decade by then. In his confession he said he was acting against the institution that had failed to offer him permanent employment, but he also hinted darkly that the lack of poverty and chastity from certain Cathedral personnel his poor, traumatized eyes had witnessed during his many years on the job drove him to a decade of thievery. The lack of chastity was homosexual, gasp, and the lack of poverty consisted in staff taking money out of the offering bag and helping themselves to the best donations of silverware, hams and fine wines.

That fits with the disgruntled employee theory of the crime. He was let go in 2011, officially due to restructuring, but possibly because he was suspected of theft. That can’t have been the source of his cleptorage, however. He may have stolen the Codex Calixtinus in July of 2011 out of pique, but he’d been making off with huge fistfuls of cash regularly for something like a decade by then. In his confession he said he was acting against the institution that had failed to offer him permanent employment, but he also hinted darkly that the lack of poverty and chastity from certain Cathedral personnel his poor, traumatized eyes had witnessed during his many years on the job drove him to a decade of thievery. The lack of chastity was homosexual, gasp, and the lack of poverty consisted in staff taking money out of the offering bag and helping themselves to the best donations of silverware, hams and fine wines.

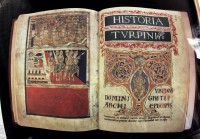

The Codex is now back at the Cathedral. It was returned on July 8th, 2012, four days after it was found in a garbage bag under some newspapers in Castiñeiras’ garage. It was on public display in the chapter house for the day, after which it was put in a safe location while the Cathedral looked into improving its obviously faulty security systems.

I can’t get over how beautiful the illustrations in the book are. I had to zoom in on that photo, the depth of color for something approx. 900 years old is amazing. I’m glad they caught him so that the public can still enjoy it.

Those colors are great indeed, the ‘T’ is truely an impressive one …And… one can clearly read it: Turpinus domini gratia archiepiscopus reojensis ac sedulus karoli magni imp[erat]oris in espania consocius leoprando decano aquisgranensi sat in xro; [sat in christo?]…

Aquisgrana is the German town of Aachen, where the depicted frankish gentleman (Charlemagne) chose to have his headquarters, and where apparently this dean by the name of leoprand was employed. So if the collection is dating from the 12th century, who else was busy with it (carolus died already in AD814) ?

Wikipedia knows: ‘Book IV is attributed to Archbishop Turpin of Reims and commonly referred to as Pseudo-Turpin, although it is the work of an anonymous writer of the 12th century. It describes the coming of Charlemagne to Spain, his defeat at the Battle of Roncevaux Pass and the death of the knight Roland’.

However, I personally think that, with reference to Turpinus, ‘archiepiscopus reojensis in espania’ does not really sound like ‘Reims’ (which is in what is now France), does it ? – Rioja, however, has -with hardly any exceptions- always been part of ‘espania’, even if carolus would probably have preferred to call it ‘next to franconia’. Let us not forget: The ‘Arabs’ were -at that time- also directly right next to it.

Moreover, they had their own treatment of theft. …

Thanks for this entry, it was unexpectedly hilarious. The guy and his lawyer must have been sitting up every night watching old courtroom drama reruns on TV to assemble that many lame defensive tactics.

I’m surprised not to hear “The Devil made me do it!”.

“the lack of poverty consisted in staff taking money out of the offering bag and helping themselves to the best donations of silverware, hams and fine wines.” Old Spanish practices.