R. Buckminster Fuller’s first prototype for the innovative Dymaxion vehicle rolled off the factory in Bridgeport, Connecticut, on July 12, 1933, her creator’s 38th birthday. If Dymaxion 1 had lived, she would be 82 years old today. Dymaxion, a portmanteau of dynamic, maximum and tension, was a brand name Fuller used for a number of his creations, from a house to a map of the globe to his sleep schedule of 30 minute naps every six hours. The Dymaxion Car wasn’t even supposed to be a car, although Fuller knew people would think of it as one. He designed it to be an “Omni Medium Transport,” a vehicle that would be able to travel by land, water and air. It’s just that “jet stilts” he envisioned to raise it in the air didn’t exist (jet engines were still 20 years in the future, vertical takeoff technology almost 30) and making it water-worthy would be too expensive and technologically daunting, so he decided to focus on the “ground-taxiing under transverse wind conditions” phase which meant in practice that his prototype was a car.

R. Buckminster Fuller’s first prototype for the innovative Dymaxion vehicle rolled off the factory in Bridgeport, Connecticut, on July 12, 1933, her creator’s 38th birthday. If Dymaxion 1 had lived, she would be 82 years old today. Dymaxion, a portmanteau of dynamic, maximum and tension, was a brand name Fuller used for a number of his creations, from a house to a map of the globe to his sleep schedule of 30 minute naps every six hours. The Dymaxion Car wasn’t even supposed to be a car, although Fuller knew people would think of it as one. He designed it to be an “Omni Medium Transport,” a vehicle that would be able to travel by land, water and air. It’s just that “jet stilts” he envisioned to raise it in the air didn’t exist (jet engines were still 20 years in the future, vertical takeoff technology almost 30) and making it water-worthy would be too expensive and technologically daunting, so he decided to focus on the “ground-taxiing under transverse wind conditions” phase which meant in practice that his prototype was a car.

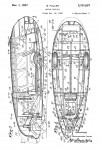

It wasn’t a car like any other, though. Teardrop shaped for optimal aerodynamicism, the Dymaxion Car was 20 feet long, had three wheels (two on in the front, one in the back) and could carry 11 passengers. It was powered by the brand new 85-horsepower Ford flathead V8 engine and had another Ford part — the rear axle of a roadster — which he converted into the front-wheel-drive axle. As large as it was, it was built on a lightweight steel chassis and skinned in aluminium sheeting making it weigh no more than a VW Beetle. It was remarkably fast — Fuller said he’d reached 128 miles per hour in a road test — and fuel-efficient, routinely getting 22 miles per gallon and capable of achieving up to 36 mpg.

Fuller and his co-designer, naval architect Starling Burgess, made three prototypes in 1933 and 1934. They filed a patent application (pdf) on October 18th, 1933, which was finally approved more than four years later on December 7th, 1937 but by then it was too late for the Dymaxion Car. At first the response to the vehicle was hugely positive. Luminaries like Amelia Earhart and Diego Rivera wanted rides. People flocked to see demonstrations of its speed and its most thrilling feature, the 20-foot-long car’s ability to turn on itself so that it could parallel park in a spot just six inches longer than its body by pulling up to the car in front of it and then drifting its back end to the curb.

Fuller and his co-designer, naval architect Starling Burgess, made three prototypes in 1933 and 1934. They filed a patent application (pdf) on October 18th, 1933, which was finally approved more than four years later on December 7th, 1937 but by then it was too late for the Dymaxion Car. At first the response to the vehicle was hugely positive. Luminaries like Amelia Earhart and Diego Rivera wanted rides. People flocked to see demonstrations of its speed and its most thrilling feature, the 20-foot-long car’s ability to turn on itself so that it could parallel park in a spot just six inches longer than its body by pulling up to the car in front of it and then drifting its back end to the curb.

Then tragedy struck. On October 27th, 1933, Dymaxion Car #1 was just in front of the entrance to the Century of Progress Exposition, the Chicago World’s Fair, when it was hit by another car that had been following it dangerously. The Dymaxion rolled over and its driver, professional racer Francis Turner, was killed. He had been wearing a seatbelt, but the button-down canvas roof collapsed, killing him. One of the passengers, British aviator, peer and Japanese spy William Sempill, was seriously injured. The other, Air Minister of France Charles Dollfuss, was thrown from the car and landed on his feet entirely unharmed. Because the driver of the car that caused the crash was an influential Chicago parks commissioner, he and his vehicle were hustled away before reporters got to the scene.

When the news of the crash hit the papers, therefore, there was no mention of another car having plowed into the Dymaxion. Instead it was the unique shape and design of the vehicle that took the blame for the fatal accident; it had hit a “wave” in the road and flipped ass over teakettle. The Dymaxion was excoriated as inherently unstable and dangerous. Because of the English and French dignitaries in the car, the crash made the international press as well. Evidence given at the coroner’s inquest, including the testimonies of Sempill and Dollfuss, exonerated the Dymaxion vehicle, but the inquest had been delayed two months to give Sempill a chance to recover from his injuries, so by the time the truth came out, the story was old news and was barely covered in the press.

When the news of the crash hit the papers, therefore, there was no mention of another car having plowed into the Dymaxion. Instead it was the unique shape and design of the vehicle that took the blame for the fatal accident; it had hit a “wave” in the road and flipped ass over teakettle. The Dymaxion was excoriated as inherently unstable and dangerous. Because of the English and French dignitaries in the car, the crash made the international press as well. Evidence given at the coroner’s inquest, including the testimonies of Sempill and Dollfuss, exonerated the Dymaxion vehicle, but the inquest had been delayed two months to give Sempill a chance to recover from his injuries, so by the time the truth came out, the story was old news and was barely covered in the press.

Fuller and Burgess repaired the prototype, and the next year they brought Dymaxion Car #3 to Chicago for the second run of the World’s Fair (the Exposition had been so lucrative that organizers reopened it from May to October of 1934). Crowds flocked to see Fuller do demonstrations like “waltzing” (a zig-zagging maneuver) down the main street and turning the car on itself. Primed by the horrible reputation the Dymaxion had been saddled with the year before, visitors expected the car to flip over. It did not. Instead it regained its reputation as a futuristic technological marvel.

Fuller and Burgess repaired the prototype, and the next year they brought Dymaxion Car #3 to Chicago for the second run of the World’s Fair (the Exposition had been so lucrative that organizers reopened it from May to October of 1934). Crowds flocked to see Fuller do demonstrations like “waltzing” (a zig-zagging maneuver) down the main street and turning the car on itself. Primed by the horrible reputation the Dymaxion had been saddled with the year before, visitors expected the car to flip over. It did not. Instead it regained its reputation as a futuristic technological marvel.

The bad press had done its damage, though. Between that and the Depression, Fuller was unable to secure investors for new prototypes. He had only managed to make the third one by selling stocks he’d inherited, going into debt and taking advantage of Henry Ford’s offer to let him have anything he wanted from the Ford line of products for 75% off. Number three would be the last of the Dymaxions. Fuller liquidated the company’s assets, paid off his creditors and called it a day.

Of the three prototypes, only one survives today. Car #1 was purchased by the U.S. Bureau of Standards. It was destroyed in a fire at the BoS’s Washington D.C. garage. Car #3 was sold to conductor Leopold Stokowski but he found he didn’t like driving it so sold it a few months later. It passed through various hands before meeting its end in a Wichita junkyard where it was cut up and sold for scrap during the 1950s. Car #2 saw some hard living (apparently it was used a chicken coop) before being sold to Las Vegas casino executive and car collector William Harrah. After his death many of Harrah’s cars were sold at auction, but Dymaxion #2 was one of a selection donated to the National Automobile Museum in Reno, Nevada, where it is on display today.

Of the three prototypes, only one survives today. Car #1 was purchased by the U.S. Bureau of Standards. It was destroyed in a fire at the BoS’s Washington D.C. garage. Car #3 was sold to conductor Leopold Stokowski but he found he didn’t like driving it so sold it a few months later. It passed through various hands before meeting its end in a Wichita junkyard where it was cut up and sold for scrap during the 1950s. Car #2 saw some hard living (apparently it was used a chicken coop) before being sold to Las Vegas casino executive and car collector William Harrah. After his death many of Harrah’s cars were sold at auction, but Dymaxion #2 was one of a selection donated to the National Automobile Museum in Reno, Nevada, where it is on display today.

Architect and Fuller collaborator Norman Foster borrowed Prototype #2 to make a replica of the Dymaxion. In return for the loan, he restored the interior of #2 which was in such atrocious condition the car’s windows were made opaque so visitors to the museum wouldn’t be able to see inside. Now that the car is back in Nevada and looking great, the museum is currently raising funds to repair the mechanics so that the Dymaxion can show off its talents on the road once again. Donors get a chance to win a ride in the Dymaxion.

Here’s a quick clip of the Dymaxion Car driving fast, turning tight and parallel parking like a boss.

[youtube=https://youtu.be/fO80IjrO9d8&w=430]

This clip features Fuller describing the vehicle and has great footage of its clown car-like ability to carry more humans than seems possible.

[youtube=https://youtu.be/S1UaC51OSPw&w=430]

Here Fuller narrates a period video of the Dymaxion in action featuring Amelia Earhart and then, in a 1975 Philadelphia talk, he discusses the car’s redemptive performance at the Century of Progress Exposition the year after the fatal accident.

[youtube=https://youtu.be/D7POp3jvikY&w=430]

The jet engine was proposed before world war one and Frank Whittle proposed his jet engine to the Air Ministry (he was turned down) in 1929. IIRC the first jet aircraft was Italian and flew in 1938. It had an external compressor rather than the compressor being internal to the engine.

If only the car had been hit by a more responsible tailgater! We could all have been driving/piloting lovely Dymaxion vehicles in that alternate universe.

I don’t know. He’s revered by many as a futurist, but it seems to me that Buckminster Fuller’s legacy were more curiosities than anything else. How much lasting influence has her really had? I don’t think we lost much. It was largely part of the Technology as Solution model that has driven much of our culture for too long. The dome sucked to live in. The car was rearended and crashed, killing one person and injuring others, while the other car and its occupants were able to leave the scene to escape blame. The touted mileage was not particularly impressive, and was due, I suspect, from the lightweight construction Fuller used. My ancient 1986 Volvo station wagon gets the same mileage and though it cannot slide sideways into a parking spot, it does have an admirable tight turning radius. If Bucky had been truly a futurist, and not just a creative guy into making curious and attention getting objects, maybe he could have contributed something meaningful to the way transportation of goods and people has developed in our country.

Pah ! Looks like one of those cabins that we used to carry around underneath of a Zeppelin plus wheels and floating capabilities 🙂

I would have to disagree with Annie on a few points. I met him at the College of the Atlantic in the early 1970’s and found many of his ideas to be quite interesting. He did a lot to support the college in its infancy and for that I believe they will always be grateful. And I also believe that no “creativity” is ever wasted. I do however, agree with Annie, that the “dome” was not an optimum space to live in. Thanks for the post.

I saw Dymaxion #2 at Harrah’s, from a distance; it was parked in the open outside the museum, along a curb, without signage or fencing. Truthfully, it looked pretty shabby at the time.

My memories of Fuller himself, from a booksigning circa 1982, are far more vivid. He had a helper with him to keep people from monopolizing his time; he gave his full attention to each person as they came up with their books. I admired his unusual wristwatch, and he showed it to me and talked about its features. And he told me I had a nice name (I gave him my full name, John Dylan Cooper—which I’d only recently adopted), and signed my copy of his book with a flourish. When the book got wet during a car trip not long after, ruining the signature, I wept.