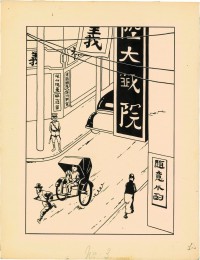

A rare original drawing of Tintin by Belgian cartoonist Georges Prosper Remi, better known as Hergé, has sold at auction in Hong Kong for $1.23 million. The India ink and gouache drawing depicts Tintin and his dog Snowy riding in a rickshaw on the streets of Shanghai while a police officer keeps a watchful eye on them. It’s the third of five single-page drawings included as color plates, the first color elements in a Tintin book, in the first edition of The Blue Lotus, published in 1936 by Casterman. The drawings from this original Casterman edition are highly prized by collectors because The Blue Lotus is considered the first masterpiece of the Hergé oeuvre. In fact, every other surviving original drawing from The Blue Lotus is in a museum; this is the only one in private hands.

A rare original drawing of Tintin by Belgian cartoonist Georges Prosper Remi, better known as Hergé, has sold at auction in Hong Kong for $1.23 million. The India ink and gouache drawing depicts Tintin and his dog Snowy riding in a rickshaw on the streets of Shanghai while a police officer keeps a watchful eye on them. It’s the third of five single-page drawings included as color plates, the first color elements in a Tintin book, in the first edition of The Blue Lotus, published in 1936 by Casterman. The drawings from this original Casterman edition are highly prized by collectors because The Blue Lotus is considered the first masterpiece of the Hergé oeuvre. In fact, every other surviving original drawing from The Blue Lotus is in a museum; this is the only one in private hands.

It’s not a record for Tintin art. That was set in May of last year when a double page of Tintin and Snowy vignettes sold for $3,434,908. It’s not even runner-up. That title goes to the original cover art of Tintin in America which sold in 2012 for $1.6 million. It is arguably a more historically significant piece, however, because Hergé included actual historic events in The Blue Lotus that had happened only five years before the publication of the volume, and because of how thoroughly researched this story was compared to his earlier outings.

When Georges Remi first began drawing Tintin comics in 1929, they were serialized in a newspaper called Le Petit Vingtième (“The Little Twentieth”). It was the children’s supplement to Le Vingtième Siècle (“The Twentieth Century”), a conservative Catholic newspaper published in Brussels whose editor, Abbé Norbert Wallez, was an outspoken nationalist, fascist fan of Mussolini. He was so ultraconservative that in 1940 he supported a Belgian political party that embraced Nazi occupation with open arms and after the war was tried and convicted of collaboration. Wallez’ ideological positions are what drove the first three volumes of Tintin. He saw Le Petit Vingtième and Hergé’s dashing young reporter as propaganda tools to spread his anti-communist, colonialist and anti-consumerist message to the youth of Belgium.

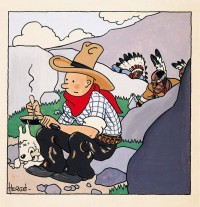

Wallez told Hergé what to write starting with Tintin in the Land of the Soviets (spoiler: the Soviets are bad), published in serialized form in 1929 and 1930, and followed by Tintin in the Congo (spoiler: the Congolese need white Belgian daddies to take care of them like the childish simpletons they are), published in 1930 and 1931. For the Tintin’s third outing, Hergé got to pick his own setting — the United States — but Wallez insisted he treat the subject with the paper’s far-right agenda which at the time held American-style capitalism, consumerism and increasingly mechanized industry to be as dangerous to the Belgian way of life as Soviet collectivism. Hergé wanted to focus on Native Americans, depicting their exploitation and rejecting the violent savage stereotype while still managing to make them look like gullible marks. Wallez won the argument, and most of the volume is about Al Capone, gangsterism and the literal meat-grinder of American industry with just a subplot about a Blackfoot tribe getting tricked into trying to kill our hero.

Wallez told Hergé what to write starting with Tintin in the Land of the Soviets (spoiler: the Soviets are bad), published in serialized form in 1929 and 1930, and followed by Tintin in the Congo (spoiler: the Congolese need white Belgian daddies to take care of them like the childish simpletons they are), published in 1930 and 1931. For the Tintin’s third outing, Hergé got to pick his own setting — the United States — but Wallez insisted he treat the subject with the paper’s far-right agenda which at the time held American-style capitalism, consumerism and increasingly mechanized industry to be as dangerous to the Belgian way of life as Soviet collectivism. Hergé wanted to focus on Native Americans, depicting their exploitation and rejecting the violent savage stereotype while still managing to make them look like gullible marks. Wallez won the argument, and most of the volume is about Al Capone, gangsterism and the literal meat-grinder of American industry with just a subplot about a Blackfoot tribe getting tricked into trying to kill our hero.

All three of these stories are problematic, to put it mildly, with the last two still causing waves today because of the stereotypical depiction of indigenous peoples. Tintin in the Congo was recently subject to a lawsuit because of its painfully racist images of the Congolese, and Tintin in America caused an uproar in Canada just a few months ago.

The fourth book, Cigars of the Pharaoh wasn’t a single pre-planned story, but rather part of a long mystery adventure à la Agatha Christie serialized as The Adventures of Tintin, Reporter, in the Orient starting in December of 1932. It was divided into two books for publication by Casterman, Cigars of the Pharaoh and The Blue Lotus. While Hergé had done some research for Tintin in America — read an ethnographic compendium of Indian tribes, visited a museum, meticulously copied Blackfoot garments from period photographs — The Blue Lotus was a whole new kettle of fish.

Chinese characters had cameos in Soviets as torturers and in America as would-be Snowy eaters, and a certain Abbot Léon Gosset wanted to stop Hergé from resorting to the same ugly stereotypes in a story set in China. He was a chaplain at the Catholic University of Louvain who had Chinese students under his tutelage. Since the students were made to read Le Petit Vingtième in class, Gosset reached out to Hergé asking him to maybe meet an actual Chinese person and learn something before tackling the subject.

Chinese characters had cameos in Soviets as torturers and in America as would-be Snowy eaters, and a certain Abbot Léon Gosset wanted to stop Hergé from resorting to the same ugly stereotypes in a story set in China. He was a chaplain at the Catholic University of Louvain who had Chinese students under his tutelage. Since the students were made to read Le Petit Vingtième in class, Gosset reached out to Hergé asking him to maybe meet an actual Chinese person and learn something before tackling the subject.

Hergé was game, and Gosset arranged for him to meet two of his students, one of whom, Zhang Chongren, introduced Hergé to the traditional Chinese art and calligraphy that would influence the Belgian artist for the rest of his life. Zhang contributed some of his own artwork to The Blue Lotus, and Hergé believed he was so important a contributor that he should share credit as co-author. (Casterman disagreed, obviously. Hergé snuck Zhang’s name in several panels on shop signs.) Hergé also contacted scholars of Chinese history, read books by contemporary Chinese authors and learned about the Japanese invasion of Manchuria from the Chinese perspective which would become a key plot point in The Blue Lotus.

The end-result was an indictment of European cluelessness about and interference in China and of the Japanese occupation. It infuriated the Japanese, who are depicted as the bucktoothed bullies that would become so familiar in American propaganda during World War II, nearly causing a diplomatic incident. The Chinese, on the other hand, accustomed to being the ones depicted as opium-addled brutes in Western fiction and media, loved it. Through his wife, Chiang Kai-shek invited Hergé to visit China as his guest in 1939, but the war made it in impossible.

This history is part of the reason the Paris auction house Artcurial chose the drawing from The Blue Lotus for its first Hong Kong sale, because it has a particular appeal to Chinese buyers.

I have a “framed drawing” or “painting” of a “hunter and his hound” that is signed “L. Lepetit” and would like to send you a photo of it for you to critique. I received it many years ago, much to the daughters dismay (I honestly thought she was going to follow me to my car and rip it from my hands)from an elderly couple whilst helping them move out of their plantation home. I know it is very old but have no knowledge regarding “art.” Through research on the Internet I have come across several images with the same characteristics. There is also another name in the opposite corner that reads “L’arris or L’arres” any help would be greatly appreciated. Thanks in advance for your time and consideration.