A team of British and Puerto Rican archaeologists have discovered a collection of early colonial inscriptions alongside earlier indigenous iconography on the walls of a cave on the Caribbean island of Mona. It’s a unique document of the interaction between indigenous and European culture and at the time of their earliest interactions.

A team of British and Puerto Rican archaeologists have discovered a collection of early colonial inscriptions alongside earlier indigenous iconography on the walls of a cave on the Caribbean island of Mona. It’s a unique document of the interaction between indigenous and European culture and at the time of their earliest interactions.

Columbus first encountered Mona, a small island between Hispaniola and Puerto Rico, on his second voyage in 1494. Its location within a day’s canoe trip of the larger islands ensured the indios of Mona were well-connected to interregional trade networks, and when the Spanish arrived, the island found itself on one of the main Atlantic routes to and from the Indies. The indigenous population sold supplies to the ships — cassava bread, water — and produced consumer goods like cotton shirts and hammocks to the first settlers. Thus the people of Mona were involved with Europeans from the beginning, modifying their own behaviors and traditions in response to first contact and colonization, and in turn having an impact on the Spanish as they and their children began to forge a new American identity.

Columbus first encountered Mona, a small island between Hispaniola and Puerto Rico, on his second voyage in 1494. Its location within a day’s canoe trip of the larger islands ensured the indios of Mona were well-connected to interregional trade networks, and when the Spanish arrived, the island found itself on one of the main Atlantic routes to and from the Indies. The indigenous population sold supplies to the ships — cassava bread, water — and produced consumer goods like cotton shirts and hammocks to the first settlers. Thus the people of Mona were involved with Europeans from the beginning, modifying their own behaviors and traditions in response to first contact and colonization, and in turn having an impact on the Spanish as they and their children began to forge a new American identity.

The archaeology of Mona reflects this cultural blending process. European glass beads, storage jars, ceramics, coins and the remains of livestock from 1493 through 1590 have been found on the island mixed with indigenous artifacts — ceramics, tools — and equipment for the processing of food. The vast cave networks dotting the Isle of Mona display the same mixing of cultures in the form of art and inscriptions on the walls and ceilings.

The archaeology of Mona reflects this cultural blending process. European glass beads, storage jars, ceramics, coins and the remains of livestock from 1493 through 1590 have been found on the island mixed with indigenous artifacts — ceramics, tools — and equipment for the processing of food. The vast cave networks dotting the Isle of Mona display the same mixing of cultures in the form of art and inscriptions on the walls and ceilings.

Mona is practically more cave than anything else. Sheer limestone cliffs line the shores, peppered with more than 200 cave systems. Because the surface of the island is thick with plant life, the cool, rocky caves became a sort of subway system where the locals could travel to other points without having to hack their way through dense vegetation. The caves were also the island’s sole source of fresh water. Clear indications of indigenous usage has been found in 30 of the 70 cave systems on the island that have been studied by archaeologists since 2013.

Mona is practically more cave than anything else. Sheer limestone cliffs line the shores, peppered with more than 200 cave systems. Because the surface of the island is thick with plant life, the cool, rocky caves became a sort of subway system where the locals could travel to other points without having to hack their way through dense vegetation. The caves were also the island’s sole source of fresh water. Clear indications of indigenous usage has been found in 30 of the 70 cave systems on the island that have been studied by archaeologists since 2013.

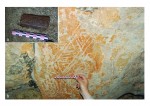

The caves of Mona have the greatest variety of surviving indigenous iconography in the Caribbean. Symbols including geometric shapes, swirling meanders, anthropomorphic and anthrozoomorphic figures have been found on the walls and ceilings of cave chambers. The inscribed caves are hard to get to, their entrances small, person-sized holes high up on the cliff face, and the indigenous artwork only appears in the deep dark inside the caves, far from the light of the entrance. These were likely deliberate choices, as caves and the iconography held religious significance. The Europeans followed, perhaps literally, in indigenous footsteps to add their own religious spin to the sacred spaces of Mona.

The caves of Mona have the greatest variety of surviving indigenous iconography in the Caribbean. Symbols including geometric shapes, swirling meanders, anthropomorphic and anthrozoomorphic figures have been found on the walls and ceilings of cave chambers. The inscribed caves are hard to get to, their entrances small, person-sized holes high up on the cliff face, and the indigenous artwork only appears in the deep dark inside the caves, far from the light of the entrance. These were likely deliberate choices, as caves and the iconography held religious significance. The Europeans followed, perhaps literally, in indigenous footsteps to add their own religious spin to the sacred spaces of Mona.

In Cave 18, archaeologists found 250 indigenous works on the walls and ceilings 10 chambers and tunnels. The soft, swirling motifs were made by “finger-fluting,” ie, dragging one or more fingers through the mineral and organic deposits on the surfaces, and have been radiocarbon dated to the 14th and 15th century. More than 30 inscriptions in Spanish and Latin followed, applied to the same areas. They include proper names, dates and Christian symbols like crosses and the IHS Christogram.

In Cave 18, archaeologists found 250 indigenous works on the walls and ceilings 10 chambers and tunnels. The soft, swirling motifs were made by “finger-fluting,” ie, dragging one or more fingers through the mineral and organic deposits on the surfaces, and have been radiocarbon dated to the 14th and 15th century. More than 30 inscriptions in Spanish and Latin followed, applied to the same areas. They include proper names, dates and Christian symbols like crosses and the IHS Christogram.

Unlike the locals who climbed and crouched to apply their artwork to a variety of locations, the Europeans added their stuff where they stood, at about 1.8 meters — average height for Europeans at that time — above the floor. Also unlike the locals, they carved their inscriptions with edged tools into the limestone.

Three inscribed phrases are present in chambers H and K: ‘Plura fecit deus’, ‘dios te perdone’ and ‘verbum caro factum est (bernardo)’. Palaeographic analysis of letter forms, the use of abbreviation and writing conventions place these in the sixteenth century…. ‘Plura fecit deus’, or ‘God made many things’, is the first inscription encountered after entering chamber H. There is no obvious contemporary textual source; the commentary appears to be a spontaneous response to whatever the visitor experienced in the cave. There is a strong spatial inference that ‘things’ is a reference to the extensive indigenous iconography present. The phrase may express the theological crisis of the New World discovery, throwing the personal human experience and reaction into sharp relief. […]

Particularly striking are two depictions of Calvary. The first consists of three crosses, the central one with the Latin inscription ‘Iesus’ (Jesus) set at a height of over 3m in chamber G…. Stylistically, all three are barred cross-on-base motifs, in use in the sixteenth century; similar examples are found from contemporary contexts in Europe and South America…. A second Calvary panel is made up of two crosses, one of which is a barred cross-on-base, the other a simple two-stroke Latin cross. These flank a pre-existing indigenous anthropomorphic figure. This triptych has clear compositional parallels with representations of Calvary in which the central figure is strikingly cast as an indigenous Jesus.

There are 17 more crosses in the cave, from simple downstroke-and-crosstroke Latin crosses to more complex Potent and Calvary crosses. Some are finger-drawn, probably by converted indios. Many of them were made near and above pre-existing indigenous iconography.

There are 17 more crosses in the cave, from simple downstroke-and-crosstroke Latin crosses to more complex Potent and Calvary crosses. Some are finger-drawn, probably by converted indios. Many of them were made near and above pre-existing indigenous iconography.

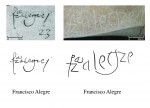

We know it wasn’t indigenous converts doing the carving because several of the Spanish artists did us the courtesy of leaving their Kilroy Wuz Here. From the mid-16th century, Myguel Rypoll,  Alonso Pérez Roldan el Mozo and Alonso de Contreras signed the wall. The above-mentioned Bernardo signed off on his “verbum caro factum est” line, and one Capitán Francisco Alegre, a royal official in Puerto Rico in the mid-16th century, signed his name. It’s actually quite impressive considering he was carving it in the wall how similar it is to his actual signature on a page.

Alonso Pérez Roldan el Mozo and Alonso de Contreras signed the wall. The above-mentioned Bernardo signed off on his “verbum caro factum est” line, and one Capitán Francisco Alegre, a royal official in Puerto Rico in the mid-16th century, signed his name. It’s actually quite impressive considering he was carving it in the wall how similar it is to his actual signature on a page.

[Dr. Alice Samson from the University of Leicester School of Archaeology and Ancient History] said the marks were made by some of the earliest colonisers to arrive in the Americas. These colonisers would have been taken to the caves, places considered particularly sacred, and were responding with respect to what they saw, engaging in a religious dialogue.

“We have this idea of when the first Europeans came to the New World of them imposing a very rigid Christianity. We know a lot about the inquisition in Mexico and Peru and the burning of libraries and the persecution of indigenous religions.

“What we are seeing in this Caribbean cave is something different. This is not zealous missionaries coming with their burning crosses, they are people engaging with a new spiritual realm and we get individual responses in the cave and it is not automatically erasure, it is engagement.”

You can read the full paper published in the journal Antiquity free of charge here.

“Because the surface of the island is thick with plant life, the cool, rocky caves became a sort of subway system where the locals could travel to other points without having to hack their way through dense vegetation. The caves were also the island’s sole source of fresh water.”

That’s so fascinating that I will forgive you the dismal “began to forge a new American identity”.

In Fig. 3 (b), what reads in the paper as “complex imagery of anthrozoomorphic and ancestral beings” (shouldn’t it rather be “anthropozoomorphic”, or as Liv correctly put it “anthropomorphic” ?), the subpic in the upper right hand corner seems to be an “indigenous portrait” of the bearded Capitán Francisco Alegre.

Apart from that, as all the “Indians” seem to have vanished on those islands, the “impact” that led to a “new American identity” might have been a rather biased one. Ok, I cannot rule out that Capitán Francisco Alegre did really not enslave anybody 😉

—————

The Welser family of Augsburg had signed an agreement to explore the territory of Venezuela and sent Nikolaus Federmann to Santo Domingo in 1529. Federmann brought settlers and miners from Seville, via Santo Domingo, to Coro in Venezuela in 1529 and 1530.

Back in Augsburg he wrote “Indianische Historia: Ein schöne kurtzweilige Historia Niclaus Federmanns des Jüngern von Ulm erster raise”, a description about his “first voyage”, published in 1557. However, in 1536, Federmann undertook a second expedition searching for the legendary El Dorado.

As far as Hispaniola is concerned, he writes for instance about the beauty of Santo Domingo, but also that the other towns were mainly inhabited by Christians that had discovered and conquered the island 40 years earlier. The natives are “naked” and “similar to the ones in Coro”, and where they once had possessed the land, they now possess none and are subdue to a forced labor system (‘Repartimento’), but only those that were still alive and not killed by smallpox.

—————

In 16th century German it reads:

Als ich nun in dieser Insel, welche Insula [His]paniola heisst, die Stadt aber [Santo] Dominigo, welche sehr wohl erbauet ist und zierliche Gassen und Edificias [edificio (span.)] hat, und hat auch ein stark wehrlich Schloss und seinen sehr guten Port – und wiewohl in dieser Insel, welche fünfhundert Meil Weg ringsum begreifet, viel der Flecken und Städt von Christen bewohnet sind, so ist doch Sant Dominigo das Haupt und beste unter allen diesen Inseln.

Unnoth von Art und Sitten der Naturales oder Einwohner, diesers Landes Art zu schreiben. Denn es nun mehr als ein Land vor vierzig Jahren von Christen erobert und gewonnen wurde, wie man weiss und es lautgeschreiig ist, mit Leuten, wie auch die zu Coro sind, als ihr hernach werdet hören, ein nacktet Volk und eben derselbigen Farbe. Sie die Naturales oder Einwohner dieses Lands, so diese Insel, ehe die Christen dahin kamen, besessen und beherrschet haben, bewohnen itzt keinen eignen Flecken, sondern sie sind den Christen gar geunterthänigt [the Indians had to work for the Spanish king, cf. ‘Repartimento’, a colonial forced labor system] und dienen den Christen so viel als von den Indios noch am Leben sind.

Aber ihrer sind doch nicht mehr viel vorhanden. Denn nach Vernehmen sollen von fünfhunderttausend Indios oder Einwohnern, so in dem Land gewest (durch die ganze Insel allerlei Nation und Sprachen, als die Christen das Land erst gefunden, welches wie obgesagt vor vierzig Jahren war) itzt nit über zwanzigtausend am Leben seien. Eine grosse Summe soll durch eine Krankheit, welche sie Viroles [smallpox, variola] heissen, auch teils in Kriegen und ein grosser Teil aus übertriebener Arbeit (darzu sie die Christen in den Goldbergwerken nötigten, welches doch wider ihre Gewohnheit ist, denn sie von Art ein zart und wenig arbeitend Volk gewest sind) gestorben sind, und sich dadurch in so kurzer Zeit eine solche Multitud und grosse Summe in eine so kleine Zahl gemindert haben, also dass itzt diese Insel und alle Flecken und Städte darinnen durch eine königliches Kammer- und Hofgericht, welches sie Audencia Real [prior to the ‘Aud(i)encias Reales’ in Panama und Lima] heissen, regiert werden, das in der Stadt Sant Domingo wohnet.