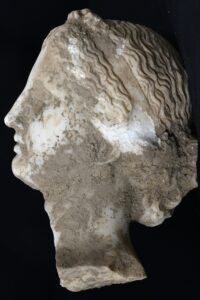

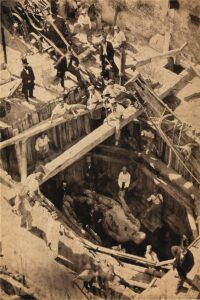

The remains of the Emperor Nero’s private theater have been discovered under the internal courtyard of the 15th century Palazzo della Rovere in Vatican City. Thus far, archaeologists have uncovered the remains of the left side of the semicircular cavea (the seating section) and of the scaenae frons, the architectural background of the Roman stage. In this area archaeologists have also unearthed finely-worked Ionic columns made of precious white and colored marbles and elegant stucco adorned with gold leaf — a type of decoration also found in Nero’s Domus Aurea. A second structure perpendicular to the stage area had service rooms, perhaps used to store scenery and costumes.

The remains of the Emperor Nero’s private theater have been discovered under the internal courtyard of the 15th century Palazzo della Rovere in Vatican City. Thus far, archaeologists have uncovered the remains of the left side of the semicircular cavea (the seating section) and of the scaenae frons, the architectural background of the Roman stage. In this area archaeologists have also unearthed finely-worked Ionic columns made of precious white and colored marbles and elegant stucco adorned with gold leaf — a type of decoration also found in Nero’s Domus Aurea. A second structure perpendicular to the stage area had service rooms, perhaps used to store scenery and costumes.

The sumptuousness of the architectural elements, the exceptional quality of the craftsmanship and the makers’ stamps on the bricks identify the building as a Julio-Claudian theater that must have been commissioned by a client of the highest rank. The stratigraphic evidence indicates it was only used as a theater for a short time. By the first decades of the 2nd century, the theater complex was already being systematically dismantled so its valuable materials could be reused. The Theatrum Neronis is the only candidate to fit the bill.

The sumptuousness of the architectural elements, the exceptional quality of the craftsmanship and the makers’ stamps on the bricks identify the building as a Julio-Claudian theater that must have been commissioned by a client of the highest rank. The stratigraphic evidence indicates it was only used as a theater for a short time. By the first decades of the 2nd century, the theater complex was already being systematically dismantled so its valuable materials could be reused. The Theatrum Neronis is the only candidate to fit the bill.

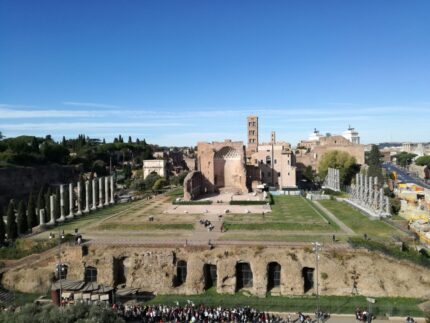

The Palazzo della Rovere was built in the late 15th century over the site of the ancient Horti Agrippinae, the gardens of the villa of Agrippina the Elder, granddaughter of Augustus, mother of the emperor Caligula and grandmother of Nero. It was a grand suburban villa outside the walls of Rome on the left bank of the Tiber and its gardens covered much of what is now Vatican City. After his mother’s death, Caligula built a circus in the gardens to stage chariot races. Nero used it to stage executions of Christians after the Great Fire of 64 A.D., including the crucifixion of Saint Peter. He was buried just a few hundred feet from the Circus on the Via Cornelia. His burial became a shrine and major pilgrimage site. Constantine built the first St. Peter’s Basilica over the shrine and remains of the Circus. The Egyptian obelisk now in St. Peter’s Square was on the spina (the central spine) of Caligula’s Circus and is revered as a witness to the martyrdom of St. Peter.

The Palazzo della Rovere was built in the late 15th century over the site of the ancient Horti Agrippinae, the gardens of the villa of Agrippina the Elder, granddaughter of Augustus, mother of the emperor Caligula and grandmother of Nero. It was a grand suburban villa outside the walls of Rome on the left bank of the Tiber and its gardens covered much of what is now Vatican City. After his mother’s death, Caligula built a circus in the gardens to stage chariot races. Nero used it to stage executions of Christians after the Great Fire of 64 A.D., including the crucifixion of Saint Peter. He was buried just a few hundred feet from the Circus on the Via Cornelia. His burial became a shrine and major pilgrimage site. Constantine built the first St. Peter’s Basilica over the shrine and remains of the Circus. The Egyptian obelisk now in St. Peter’s Square was on the spina (the central spine) of Caligula’s Circus and is revered as a witness to the martyrdom of St. Peter.

Nero added a theater next to the circus so he could have a dedicated space to perform his dubious poetry and songs before his adoring public. Or not so adoring, if Suetonius is anything to go by:

While [Nero] was singing no one was allowed to leave the theatre even for the most urgent reasons. And so it is said that some women gave birth to children there, while many who were worn out with listening and applauding, secretly leaped from the wall, since the gates at the entrance were closed, or feigned death and were carried out as if for burial.

Only this reference and a couple of others by Pliny the Elder and Tacitus mention Nero’s theater, and they are vague as to location. Over the centuries the theater had taken on a semi-legendary quality, especially since the ancient sources focus heavily on Nero’s excesses, even to the point of exaggeration.

The streets and piazzas around St. Peter’s were drastically altered during the Fascist redesign of Rome in the 1930s. Construction on the Via della Conciliazione, the broad boulevard leading directly from the Castel Sant’Angelo to the basilica, began in 1936 and numerous palaces and churches were demolished or moved to make room for the wide thoroughfare. The Palazzo della Rovere managed to survive the destruction and its façade now looks onto the Via della Conciliazione.

The streets and piazzas around St. Peter’s were drastically altered during the Fascist redesign of Rome in the 1930s. Construction on the Via della Conciliazione, the broad boulevard leading directly from the Castel Sant’Angelo to the basilica, began in 1936 and numerous palaces and churches were demolished or moved to make room for the wide thoroughfare. The Palazzo della Rovere managed to survive the destruction and its façade now looks onto the Via della Conciliazione.

The Equestrian Order of the Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem was given the palace as their new headquarters by Pope Pius XII in 1940. The order has recently leased the palazzo to the Four Seasons Hotel and Resorts group and the building and grounds are undergoing renovations with a planned grand opening in 2025, a Jubilee year. Obviously the site is archaeologically important, so excavations were a requirement in advance of construction.

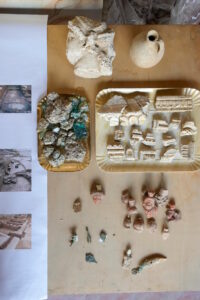

Archaeologists also found medieval remains at the site, evidence of its popularity as a pilgrimage site due to the connection to St. Peter.

Archaeologists also found medieval remains at the site, evidence of its popularity as a pilgrimage site due to the connection to St. Peter.

Among the discoveries are 10th century AD glass coloured goblets and pottery pieces that are unusual because so little is known about this period in Rome. […]

Marzia Di Mento, the site’s chief archaeologist, noted that previously only seven glass chalices of the era had been found, and that the excavations of this one site turned up seven more.

All of the portable artifacts will be removed and conserved for eventual museum display. The current plan is to cover up the remains of the theater, but I’m crossing my fingers that the hotel business people are at least as smart as the fast food and grocery people and they’ll cover it with a clear protective layer to make their courtyard into an archaeological park.

All of the portable artifacts will be removed and conserved for eventual museum display. The current plan is to cover up the remains of the theater, but I’m crossing my fingers that the hotel business people are at least as smart as the fast food and grocery people and they’ll cover it with a clear protective layer to make their courtyard into an archaeological park.