It all began in 1952 when a team of archaeologists from the Roman and Medieval London Excavation Council dug a few exploratory trenches on a construction site in central London’s Walbrook Square. Victorian buildings on the site had been all but leveled by German bombs during the Blitz. The ruins were slated to be demolished a new office block for an insurance company to be built at the location. The only reason archaeologists were there is that the lost river Walbrook had once flowed through the area so the site was surveyed to record alluvial deposits that would establish how the Walbrook changed over time. Informative, but far from glamorous.

It all began in 1952 when a team of archaeologists from the Roman and Medieval London Excavation Council dug a few exploratory trenches on a construction site in central London’s Walbrook Square. Victorian buildings on the site had been all but leveled by German bombs during the Blitz. The ruins were slated to be demolished a new office block for an insurance company to be built at the location. The only reason archaeologists were there is that the lost river Walbrook had once flowed through the area so the site was surveyed to record alluvial deposits that would establish how the Walbrook changed over time. Informative, but far from glamorous.

For two years the excavation, led by Welsh archaeologist Professor William Francis Grimes and Audrey Williams, puttered along drawing no interest whatsoever. They were almost done when the team unearthed the walls and floors of a stone building from the Roman period. They thought it was a private villa or maybe a public building until in mid-September they found an  altar at one end that identified the structure as a temple. As historically significant a find as it was, it was still slated to be destroyed to make way for the ugly new grey box of offices.

altar at one end that identified the structure as a temple. As historically significant a find as it was, it was still slated to be destroyed to make way for the ugly new grey box of offices.

Then on Saturday, September 18th, 1954, the last day of the excavation, a marble head of the god Mithras, identifiable by his characteristic Phrygian cap, was found. The handsome young deity would have gone unnoticed too if it hadn’t been for a newspaper photographer from nearby Fleet Street who was on the spot and took some pictures. They were printed the next day in The Sunday Times and caused an immediate sensation.

For weeks it was front page news. Immense crowds flocked to the site to see the temple, an estimated 400,000 people in total. The question of the temple’s dire fate was now a national scandal. It was debated in Parliament and twice in the Cabinet of Prime Minister Sir Winston Churchill. The problem was nobody had the money to preserve the temple in situ. The government was broke and the developers couldn’t afford to move the planned building. Ultimately a compromise was worked out: the Ministry of Works would fund additional excavation and the developers would pay to remove the temple and reconstruct it at ground level for public display.

For weeks it was front page news. Immense crowds flocked to the site to see the temple, an estimated 400,000 people in total. The question of the temple’s dire fate was now a national scandal. It was debated in Parliament and twice in the Cabinet of Prime Minister Sir Winston Churchill. The problem was nobody had the money to preserve the temple in situ. The government was broke and the developers couldn’t afford to move the planned building. Ultimately a compromise was worked out: the Ministry of Works would fund additional excavation and the developers would pay to remove the temple and reconstruct it at ground level for public display.

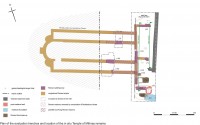

The extended excavations unearthed more sculptures — a group including Minerva, the hand of Mithras and a head of Serapis that were deliberately buried under the nave perhaps to keep them safe from depredation or as a respectful deposition when the temple was rebuilt and re-dedicated to the god Bacchus. Pottery from the earliest layers indicates the Mithraeum was first built around 240 A.D. It was extensively reconstructed in 350 A.D. after which it remained in use until the end of the Roman period.

The extended excavations unearthed more sculptures — a group including Minerva, the hand of Mithras and a head of Serapis that were deliberately buried under the nave perhaps to keep them safe from depredation or as a respectful deposition when the temple was rebuilt and re-dedicated to the god Bacchus. Pottery from the earliest layers indicates the Mithraeum was first built around 240 A.D. It was extensively reconstructed in 350 A.D. after which it remained in use until the end of the Roman period.

The sculptures were conserved and put on display in the Museum of London where they joined a relief of Mithras slaying the Bull of Heaven that had been unearthed at Walbrook in 1889. The relief has an inscription that may shed light on the temple’s construction: “Ulpius Silvanus / Emeritus Leg(ionis) II Aug(ustae) / Votum Solvit / Factus Arausione” meaning “Ulpius Silvanus / veteran of the Second August Legion / paid his vow / made at Orange.” “Made” in this case doesn’t refer to the relief sculpture, but rather to Ulpius Silvanus himself, either he was discharged (made a veteran) or initiated into the Mithraic religion (made a devotee of Mithras). The Walbrook Mithraeum itself could be the vow he paid.

The sculptures were conserved and put on display in the Museum of London where they joined a relief of Mithras slaying the Bull of Heaven that had been unearthed at Walbrook in 1889. The relief has an inscription that may shed light on the temple’s construction: “Ulpius Silvanus / Emeritus Leg(ionis) II Aug(ustae) / Votum Solvit / Factus Arausione” meaning “Ulpius Silvanus / veteran of the Second August Legion / paid his vow / made at Orange.” “Made” in this case doesn’t refer to the relief sculpture, but rather to Ulpius Silvanus himself, either he was discharged (made a veteran) or initiated into the Mithraic religion (made a devotee of Mithras). The Walbrook Mithraeum itself could be the vow he paid.

The temple was rebuilt in 1962 on Queen Victoria Street, 300 feet or so from its find site and 30 feet above its original depth. The ancient masonry was put back together using modern cement mortar on a crazy-paving floor. The original floor was wood. We know this because some of the joists were found during the excavation thanks to the preserving power of the waterlogged Walbrook soil. It looked … weird, to put it generously, out of place and squat and not at all like it had looked in situ. Grimes said the 1962 rebuild was “virtually meaningless as a reconstruction of a mithraeum.”

The temple was rebuilt in 1962 on Queen Victoria Street, 300 feet or so from its find site and 30 feet above its original depth. The ancient masonry was put back together using modern cement mortar on a crazy-paving floor. The original floor was wood. We know this because some of the joists were found during the excavation thanks to the preserving power of the waterlogged Walbrook soil. It looked … weird, to put it generously, out of place and squat and not at all like it had looked in situ. Grimes said the 1962 rebuild was “virtually meaningless as a reconstruction of a mithraeum.”

In December 2010, Bloomberg LP bought the Walbrook Square site to build its new European headquarters. The archaeological survey has retread some of the same ground as the Grimes excavation but has found oh so much more amazingness. The new complex will integrate the archaeological discoveries into the construction, and the Temple of Mithras will be part of that plan. In 2011, stonemasons carefully dismantled the reconstructed temple, removing the 1960s concrete and carefully storing the original Roman stone and tile. It will be rebuilt with a care for authenticity this time, installed 25 feet below ground level in the same spot where it was found. The underground space will be a public exhibition area in the Bloomberg building. The building is scheduled to be complete in 2017.

In December 2010, Bloomberg LP bought the Walbrook Square site to build its new European headquarters. The archaeological survey has retread some of the same ground as the Grimes excavation but has found oh so much more amazingness. The new complex will integrate the archaeological discoveries into the construction, and the Temple of Mithras will be part of that plan. In 2011, stonemasons carefully dismantled the reconstructed temple, removing the 1960s concrete and carefully storing the original Roman stone and tile. It will be rebuilt with a care for authenticity this time, installed 25 feet below ground level in the same spot where it was found. The underground space will be a public exhibition area in the Bloomberg building. The building is scheduled to be complete in 2017.

The Museum of London is collaborating with Bloomberg to ensure the Walbrook Mithraeum re-reconstruction is done properly this time. The museum has extensive records from 1954, but they have no extant color images of the temple in situ. In order to get as many details as possible about the temple, both for the reconstruction and to more thoroughly document this exceptional find while people who remember it are still around, the museum is collecting oral histories, pictures, home movies, ephemera about the 1954 dig.

The Museum of London is collaborating with Bloomberg to ensure the Walbrook Mithraeum re-reconstruction is done properly this time. The museum has extensive records from 1954, but they have no extant color images of the temple in situ. In order to get as many details as possible about the temple, both for the reconstruction and to more thoroughly document this exceptional find while people who remember it are still around, the museum is collecting oral histories, pictures, home movies, ephemera about the 1954 dig.

They’re also hoping someone somewhere may have some actual pieces of Roman stone or mortar. At the time, construction workers and visitors were known to have pilfered themselves some souvenirs, so there could well be something very important cluttering up people’s attics that they may not even realize. Anything that reveals the original color of the stones, bricks, tiles and mortar would be very helpful. The oral histories, images, etc. will be included as part of the Temple exhibition in the Bloomberg building.

They’re also hoping someone somewhere may have some actual pieces of Roman stone or mortar. At the time, construction workers and visitors were known to have pilfered themselves some souvenirs, so there could well be something very important cluttering up people’s attics that they may not even realize. Anything that reveals the original color of the stones, bricks, tiles and mortar would be very helpful. The oral histories, images, etc. will be included as part of the Temple exhibition in the Bloomberg building.

If you have any memories, information, images or souvenirs of the 1954 excavation, email the Museum of London at oralhistory@mola.org.uk or call them at 020 7410 2266 during office hours.

Now, thanks to the ever-delightful Pathé archive, please enjoy two newsreels about the dig. The first is a short clip of the excavation site. The fellow with the glasses is Harold Plenderleith, a pioneering conservator and archaeologist who part of the team who excavated King Tutankhamun’s tomb, Sir Leonard Woolley’s digs at Ur, and the Sutton Hoo ship burial. How’s that for an archaeological trifecta?

[youtube=http://youtu.be/leUQnbh0458&w=430]

A more detailed look at the sculptures recovered and their conservation:

[youtube=http://youtu.be/bRV-vskr1Nc&w=430]