In an archaeological first, the skeletal remains of a man who was buried with his ankles shackled and padlocked together have been discovered in Great Casterton, eastern England. Radiocarbon analysis dates the bones to 226 to 427 A.D. Roman types of shackles — neck-shackles, manacles and fetters — have been found before in Britain, but this is the first time they’ve been discovered in a burial context still attached to the last person locked into them.

In an archaeological first, the skeletal remains of a man who was buried with his ankles shackled and padlocked together have been discovered in Great Casterton, eastern England. Radiocarbon analysis dates the bones to 226 to 427 A.D. Roman types of shackles — neck-shackles, manacles and fetters — have been found before in Britain, but this is the first time they’ve been discovered in a burial context still attached to the last person locked into them.

The body was discovered in 2015 by builders digging a foundation for a new conservatory. They stopped when the bones were exposed and archaeologists took over, excavating the skeletal remains and revealed the ankle fetters. The skeleton was on its right side, left arm flexed and elevated, right arm by the hip. The position suggests the body was casually thrown into the grave, not placed. The grave was not purpose-dug, but rather a pre-existing ditch as evidenced by the nature of the fill.

Osteological analysis found the deceased was a male between 26 and 35 years old when he died. Lesions with new bone formation were found on his tibiae, evidence of an unclassified trauma, and a bony spur on the femur attests to an injury caused either one traumatic event or repetitive physical activity. The skull and cervical vertebrae were missing, destroyed by modern utility works.

Ancient shackles have been widely interpreted as the material remains of Roman slavery, but the existence of shackles says nothing about the status of the people made to wear them. They could have been free-born prisoners awaiting trial, for example, and we know they were certainly worn by convicts on chain gangs. Most of the Roman shackles found in Britain were in rural locations, however, which suggests they were worn by people who worked the rural agricultural estates and mines, whether enslaved, condemned or subject to abusive discipline (ie, made to wear shackles as humiliating and painful punishment).

The iron fetters and padlock are heavily corroded, but X-rays revealed they are of the Sombernon type found in Gaul and Britain. Two penannular loops slide onto a crossbar on a pivoting iron ring. The bar curves around to a padlock. Both bar and padlock have an aperture through which a bolt is inserted to lock the shackles with an L-shaped key. When locked, both ankle hoops were fastened to each other via the bar. In this example, the fetters were reinforced with additional iron strips and bolt is still in its locked position.

The iron fetters and padlock are heavily corroded, but X-rays revealed they are of the Sombernon type found in Gaul and Britain. Two penannular loops slide onto a crossbar on a pivoting iron ring. The bar curves around to a padlock. Both bar and padlock have an aperture through which a bolt is inserted to lock the shackles with an L-shaped key. When locked, both ankle hoops were fastened to each other via the bar. In this example, the fetters were reinforced with additional iron strips and bolt is still in its locked position.

These types of fetters would have allowed some limited foot movement, enough to take tiny slow steps less than half the length of a natural stride. Doing agricultural labor with such restricted foot mobility would be challenging, to say the least. We know from literary sources that miners were chained with fetters that left their upper bodies free.

The Great Casterton burial is perhaps the best candidate for the remains of a slave in Roman Britain. By providing evidence for the use of shackles, the burial illustrates some of the potential consequences of slavery and re-emphasises our obligation to engage with this topic at a level beyond the scarce epigraphic sources available for the province. However, it does not resolve the larger problem of identifying the enslaved of Roman Britain. The man’s precise legal status remains a moot point, as others punished and coerced into labour, such as convicts and coloni, could also be chained in the manner of slaves. Some of the burials in iron restraints may well have been executed convicts but, unfortunately, due to truncation, it is unclear whether the fettered individual from Great Casterton had been decapitated like some of the iron-ring burials from York and London and several other burials in the nearby cemetery. While we might wish to use this burial to define criteria that would allow us to identify other people who had been shackled, this does not seem to be possible. The bioarchaeological evidence provides some suggestion of stress and physical activity, and there is lower leg pathology that could have been caused by the fetters. Similarly, the bony spur present on the left thigh bone could be a result of intentional blows to the leg. However, none of this evidence is strictly diagnostic, and in isolation from the fetters it would certainly be insufficient to identify the individual as being a slave. Even here the evidence for slave status cannot be considered conclusive, and, short of epigraphic evidence, determining the precise lived experiences and/or legal status of the individual is impossible.

The study has been published in the journal Britannia and can be read here.

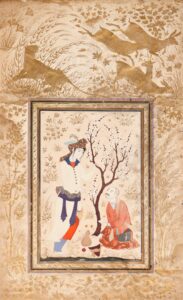

The Rijksmuseum has acquired a unique Persian miniature with a Dutch inscription that dates to the early 17th century. The Dutch handwriting on the back marks the miniature as the earliest known example of Persian art in the Netherlands.

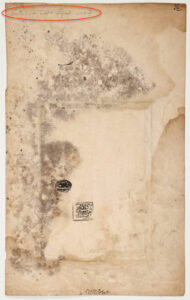

The Rijksmuseum has acquired a unique Persian miniature with a Dutch inscription that dates to the early 17th century. The Dutch handwriting on the back marks the miniature as the earliest known example of Persian art in the Netherlands. On the back is an inked inscription that reads “kalawat en sijne mat,” but its precise meaning is unknown. It does appear in Indonesian literature as the world for prince, and “mat” was an abbreviation for “majesty.” Rijksmuseum researchers believe the inscription is a curatorial note, evidence that the miniature was part of a Dutch collection shortly after it was made.

On the back is an inked inscription that reads “kalawat en sijne mat,” but its precise meaning is unknown. It does appear in Indonesian literature as the world for prince, and “mat” was an abbreviation for “majesty.” Rijksmuseum researchers believe the inscription is a curatorial note, evidence that the miniature was part of a Dutch collection shortly after it was made.