A pottery jar containing chicken remains and engraved with the names of more than 55 curse targets has been discovered in the ancient Agora of Athens. Pierced with an iron nail and buried in a corner of the Classical Commercial Building around 300 B.C., the vessel was a class-action curse, an offering of dismembered chicken parts to the underworld deities to hobble the bodies and minds of dozens of named opponents.

A pottery jar containing chicken remains and engraved with the names of more than 55 curse targets has been discovered in the ancient Agora of Athens. Pierced with an iron nail and buried in a corner of the Classical Commercial Building around 300 B.C., the vessel was a class-action curse, an offering of dismembered chicken parts to the underworld deities to hobble the bodies and minds of dozens of named opponents.

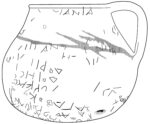

The jar, a rounded cooking pot known as a chytra, was unearthed in 2006 by archaeologists from the American School of Classical Studies at Athens but has only now been fully translated and published, revealing that the  simple unglazed pot was intended to be a weapon of mass destruction. The names of the curse victims were inscribed on the sides and bottom of the pot in two different hands. Today about 30 full names are legible; the rest have worn over the centuries and now survive only as a disconnected letter or lines. Inside were the remains of the head and lower legs of a chicken and one bronze coin.

simple unglazed pot was intended to be a weapon of mass destruction. The names of the curse victims were inscribed on the sides and bottom of the pot in two different hands. Today about 30 full names are legible; the rest have worn over the centuries and now survive only as a disconnected letter or lines. Inside were the remains of the head and lower legs of a chicken and one bronze coin.

The experts involved in the discovery believe that the nail and chicken parts together most likely played a role in the curse on the 55 different individuals. Nails, which are a common feature associated with ancient curses, “had an inhibiting force and symbolically immobilized or restrained the faculties of (the curse’s) victims,” [Yale Classics professor Jessica] Lamont stated in her scholarly article.

The archaeologists determined that the chicken that had been killed had been no older than seven months before it was slaughtered to be used as part of the ritual; they believe that the people who employed the magic may have wanted to transfer “the chick’s helplessness and inability to protect itself” to those they cursed by writing their names on the outside of the jar, Lamont stated.

She further explains that the head of the chicken, which had been twisted off, and its piercing, along its the lower legs, meant that the corresponding body parts in the 55 unfortunate people would also be similarly affected.

“By twisting off and piercing the head and lower legs of the chicken, the curse sought to incapacitate the use of those same body parts in their victims,” Lamont notes.

Lead curse tablets were the most common means to activate the power of chthonic deities against enemies in antiquity. Thirty of them were found in just one 4th century B.C. well in Athens. Curse jars are far more rare. Tablet or pot, the mechanism of most of these curses was the same: they were binding spells, intended to disable a rival’s physical and cognitive prowess. The target would be named, the curse articulated, a nail driven through the conveyance which would then be buried, often near a source of water, to put them in closer proximity to the underworld gods being invoked.

Lead curse tablets were the most common means to activate the power of chthonic deities against enemies in antiquity. Thirty of them were found in just one 4th century B.C. well in Athens. Curse jars are far more rare. Tablet or pot, the mechanism of most of these curses was the same: they were binding spells, intended to disable a rival’s physical and cognitive prowess. The target would be named, the curse articulated, a nail driven through the conveyance which would then be buried, often near a source of water, to put them in closer proximity to the underworld gods being invoked.

The use of a pot in this case is extremely unusual, and may be directly connected to the beef. With so many names on the curse list, it’s likely the conflict was over a court case. Legal disputes were the subject of many of the Athenian curse tablets, and everyone involved, from litigants to lawyers to judges to witnesses, were often targeted for binding spells. Given the jar’s burial in a commercial building known to have been used by potters, it’s possible the vessel was used rather than a more traditional lead tablet to inhibit participants in a potter-related lawsuit.

The use of a pot in this case is extremely unusual, and may be directly connected to the beef. With so many names on the curse list, it’s likely the conflict was over a court case. Legal disputes were the subject of many of the Athenian curse tablets, and everyone involved, from litigants to lawyers to judges to witnesses, were often targeted for binding spells. Given the jar’s burial in a commercial building known to have been used by potters, it’s possible the vessel was used rather than a more traditional lead tablet to inhibit participants in a potter-related lawsuit.