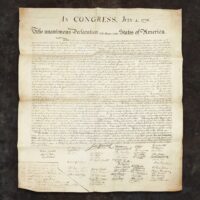

A rare facsimile of the Declaration of Independence that was presented to signatory Charles Carroll in 1824 was rediscovered in the attic of a Scottish estate. It was found in a pile of dusty documents by Cathy Marsden, Specialist in Rare Books, Manuscripts & Maps for auction house Lyon & Turnbull, who recognized it as one of only 52 surviving examples of the 200 special prints and the only example belonging to a signatory of the Declaration of Independence still in private hands.

A rare facsimile of the Declaration of Independence that was presented to signatory Charles Carroll in 1824 was rediscovered in the attic of a Scottish estate. It was found in a pile of dusty documents by Cathy Marsden, Specialist in Rare Books, Manuscripts & Maps for auction house Lyon & Turnbull, who recognized it as one of only 52 surviving examples of the 200 special prints and the only example belonging to a signatory of the Declaration of Independence still in private hands.

A brief timeline of the birth of the Declaration of Independence:

- July 2, 1776: Twelve of 13 colonial delegations in Continental Congress resolve that the United States is “Free and Independent.” New York abstains (courteously).

- July 4: Thomas Jefferson’s final draft of the Declaration is approved.

- July 4 PM: Official printer to Congress John Dunlap receives the approved text and prints it as broadsides signed by President of the Second Continental Congress John Hancock and Secretary Charles Thomson.

- July 9: New York approves the resolution of independence

- July 19: The last straggler state corralled, Congress orders that the Declaration be “fairly engrossed on parchment, with the title and stile of ‘The unanimous declaration of the thirteen United States of America,’ and that the same, when engrossed, be signed by every member of Congress.” The elegant, clear hand that quills the manuscript is likely that of Timothy Matlack, Thomson’s clerk.

- August 2: Engrossed Declaration signed by all delegates present at a signing ceremony.

The engrossed Declaration with its iconic header and John Hancock signature is now in the Rotunda of the National Archives, protected by a custom state-of-the-art encasement, but it was not so gingerly handled when it was young and the ink is barely legible today. It went with the Continental Congress during the War of Independence, rolled up, folded, transported in chests and saddlebags. Between 1776 and 1790, it lived a transient existence, touching down in Philadelphia, Baltimore, Philadelphia again, Lancaster, York, Princeton, Annapolis, Trenton and New York. It spent another decade being moved around to different locations in Philadelphia before making its way via river and ocean voyage to the newly-founded capital of Washington, D.C. It had to be hustled out of the city in a farm wagon only days before the British attack on Washington in August 1814. It returned for good in September.

The engrossed Declaration with its iconic header and John Hancock signature is now in the Rotunda of the National Archives, protected by a custom state-of-the-art encasement, but it was not so gingerly handled when it was young and the ink is barely legible today. It went with the Continental Congress during the War of Independence, rolled up, folded, transported in chests and saddlebags. Between 1776 and 1790, it lived a transient existence, touching down in Philadelphia, Baltimore, Philadelphia again, Lancaster, York, Princeton, Annapolis, Trenton and New York. It spent another decade being moved around to different locations in Philadelphia before making its way via river and ocean voyage to the newly-founded capital of Washington, D.C. It had to be hustled out of the city in a farm wagon only days before the British attack on Washington in August 1814. It returned for good in September.

By the time it achieved geographic stability, the Declaration’s iron gall ink was already destabilized and it got worse quickly. For decades it was exposed to moisture, faded in the sun, palpated by visitors, historians and copyists. In the 19th century, copies were made using a “wet transfer” method in which a damp sheet of paper was pressed into the manuscript until enough ink was absorbed so it could be transferred to a copper plate. Every pressing by design removed ink from the original.

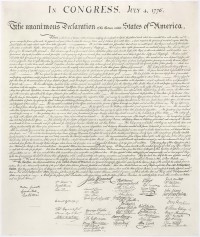

One of those copies was so meticulous a reproduction that it has become the most widespread and recognizable image of the Declaration of Independence. It was commissioned in 1820 by Secretary of State John Quincy Adams who wanted a full-size, exact copy — no extra ornament, nothing missing, everything the same including the signatures — on a copperplate so the State Department (then the custodian of the archives) could release replica prints on parchment without inflicting further damage on the original. D.C. printer William J. Stone spent three years engraving the image on a copperplate. In May 1824, Congress ordered 201 copies of the Stone engraving for distribution to luminaries and institutions. Just 52 of them are known to survive today.

One of those copies was so meticulous a reproduction that it has become the most widespread and recognizable image of the Declaration of Independence. It was commissioned in 1820 by Secretary of State John Quincy Adams who wanted a full-size, exact copy — no extra ornament, nothing missing, everything the same including the signatures — on a copperplate so the State Department (then the custodian of the archives) could release replica prints on parchment without inflicting further damage on the original. D.C. printer William J. Stone spent three years engraving the image on a copperplate. In May 1824, Congress ordered 201 copies of the Stone engraving for distribution to luminaries and institutions. Just 52 of them are known to survive today.

Six of them were gifts for the surviving signatories. John Adams, Thomas Jefferson and Charles Carroll each received two copies. Adams’ copies are now in the Massachusetts Historical Society. Jefferson’s are lost. On August 2, 1826, less than a month after Adams and Jefferson died within hours of each other on the Fourth of July, Carroll gave one of his copies to his grandson-in-law John MacTavish, diplomat and scion of a Scottish-Canadian fur trading dynasty who had married Carroll’s granddaughter Emily Caton. MacTavish gave it to the nascent Maryland Historical Society in 1844 when he served as British Consul to Maryland.

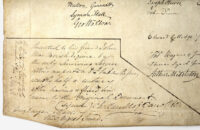

Charles Carroll, the only Catholic and last living signatory of the Declaration of Independence, died in 1832. The fate of Carroll’s second copy was unknown, but now that it’s been found in the attic, John MacTavish’s inscription makes it clear that the second copy stayed in the family via Emily Caton and was passed down through the Scottish branch of Carroll’s descendants.

Charles Carroll, the only Catholic and last living signatory of the Declaration of Independence, died in 1832. The fate of Carroll’s second copy was unknown, but now that it’s been found in the attic, John MacTavish’s inscription makes it clear that the second copy stayed in the family via Emily Caton and was passed down through the Scottish branch of Carroll’s descendants.

The inscriptions in the lower left corner of the example here tell the story of Carroll’s disposition of both of the copies he was given: “Presented to his friend John/Mac Tavish Esquire by/the only Surviving Signer/of this important State Paper,/exactly half a century/after having affixed his/name to the Original Document./(Signed) Ch. Carroll of Carrollton/ Doughoregan Manor/1826, August Second.” The signer wrote that inscription on his other copy before giving it to MacTavish, who copied it onto this document (so Carroll’s “signature” here was penned by MacTavish), and then added: “The Original presented/to the Hist: Soc: of Md/November 30/[18]44./JMc T.”

The Carroll copy was offered in a single-lot auction on July 1st at Freeman’s auction in Philadelphia, blocks away from Independence Hall where the original Declaration of Independence was signed. The pre-sale estimate was $500,000 – 800,000. Surprisingly absolutely no one, it blew past those figures and sold for $4,420,000.