Archaeologists have discovered an rare early Iron Age tomb with bronze and pottery grave goods under a mall parking lot in the town of Este, near Padua in northern Italy. The artifacts date the tomb to between the end of the 5th and the 4th century B.C.

Archaeologists have discovered an rare early Iron Age tomb with bronze and pottery grave goods under a mall parking lot in the town of Este, near Padua in northern Italy. The artifacts date the tomb to between the end of the 5th and the 4th century B.C.

The town of Este is the type site of the proto-Italic Este culture who inhabited what is today the northeastern Italian region of Veneto from the Bronze Age (10th c. B.C.) until Rome took over in the 1st century B.C. The Adriatic Veneti, after whom the region is named, also settled the area. The tomb is consistent with the burial practices of the Veneti.

The preventative archaeology excavation took place between May and July of 2019 during work on the water system of the shopping center. Pre-Roman tombs had been found in the area in the late 19th century and again when the mall was built in 1982. Several more tombs were unearthed, and with a tight deadline and construction looming, archaeologists removed all archaeological materials in soil blocks for excavation in the laboratory.

The preventative archaeology excavation took place between May and July of 2019 during work on the water system of the shopping center. Pre-Roman tombs had been found in the area in the late 19th century and again when the mall was built in 1982. Several more tombs were unearthed, and with a tight deadline and construction looming, archaeologists removed all archaeological materials in soil blocks for excavation in the laboratory.

The full excavation and conservation of the contents of one of the tombs, Tomb 6, has just been completed and the finds announced for the first time. It is a cremation burial placed in a cist formed of slabs of pink limestone native to the Euganean Hills overlooking the town. Inside the cist was a situliform vase (pottery shaped in the truncated cone typical of situlae, or buckets) used to hold the cinerary remains of the deceased. The red clay pot is decorated with bands of black. Two stemmed ceramic drinking cups with a similar black band design were also inside the box, as were another cup and a glass. A fibula of the Certosa type among the grave goods provided the key clue for the preliminary date of Tomb 6.

The full excavation and conservation of the contents of one of the tombs, Tomb 6, has just been completed and the finds announced for the first time. It is a cremation burial placed in a cist formed of slabs of pink limestone native to the Euganean Hills overlooking the town. Inside the cist was a situliform vase (pottery shaped in the truncated cone typical of situlae, or buckets) used to hold the cinerary remains of the deceased. The red clay pot is decorated with bands of black. Two stemmed ceramic drinking cups with a similar black band design were also inside the box, as were another cup and a glass. A fibula of the Certosa type among the grave goods provided the key clue for the preliminary date of Tomb 6.

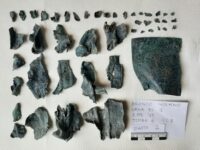

The most compelling elements of the funerary furnishings are also what made it extremely challenging to excavate: bronze artifacts including a long scepter and a bronze belt. The scepter was placed on the bottom of the cist and is in four pieces. Stuck to the body of the situliform vase was a finely engraved bronze belt. Archaeologists believe this was a ritual “dressing” of the ossuary, a funerary practice encountered in previous tombs of the ancient Veneti. The belt is in fragments as well and all that remains today are the rich bronze fittings — a large rectangular front plate, the terminals and gauge ring — which were likely originally mounted to an organic material, now decayed.

The most compelling elements of the funerary furnishings are also what made it extremely challenging to excavate: bronze artifacts including a long scepter and a bronze belt. The scepter was placed on the bottom of the cist and is in four pieces. Stuck to the body of the situliform vase was a finely engraved bronze belt. Archaeologists believe this was a ritual “dressing” of the ossuary, a funerary practice encountered in previous tombs of the ancient Veneti. The belt is in fragments as well and all that remains today are the rich bronze fittings — a large rectangular front plate, the terminals and gauge ring — which were likely originally mounted to an organic material, now decayed.

There is bronze inside the urn as well. In addition to the bone fragments and ashes inside the vase, the excavation revealed numerous fragments of bronze sheeting, some bearing the tell-tale signs of combustion. Archaeologists believe this was a belt too, worn by the deceased on the funeral pyre. The largest of the fragments is engraved with a representation of a winged animal that is frequently seen in Venetic funerary contexts.

There is bronze inside the urn as well. In addition to the bone fragments and ashes inside the vase, the excavation revealed numerous fragments of bronze sheeting, some bearing the tell-tale signs of combustion. Archaeologists believe this was a belt too, worn by the deceased on the funeral pyre. The largest of the fragments is engraved with a representation of a winged animal that is frequently seen in Venetic funerary contexts.

The remains and objects in Tomb 6 are undergoing further study for scientific publication. Meanwhile, archaeologists will turn their thorn scalpels and teeny brushes to work on the other tombs recovered from the necropolis in 2019.