The excavation of an important Gallo-Roman sanctuary outside of Rennes in Brittany has yielded an exceptional Roman bronze cup decorated with the attributes of the god Jupiter, and a bronze figurine of the god Mars.

The excavation of an important Gallo-Roman sanctuary outside of Rennes in Brittany has yielded an exceptional Roman bronze cup decorated with the attributes of the god Jupiter, and a bronze figurine of the god Mars.

The site in the village of Chapelle-des-Fougeretz has been slated for development, triggering a comprehensive preventative archaeology excavation of more than seven hectares of the site. Since the dig began in March, archaeologists have unearthed remains from a Gallo-Roman temple complex built immediately after the Roman conquest in the 1st century B.C. and in use at least through the 4th century A.D.

The site in the village of Chapelle-des-Fougeretz has been slated for development, triggering a comprehensive preventative archaeology excavation of more than seven hectares of the site. Since the dig began in March, archaeologists have unearthed remains from a Gallo-Roman temple complex built immediately after the Roman conquest in the 1st century B.C. and in use at least through the 4th century A.D.

The hilltop sanctuary, visible from Condate (modern-day Rennes) just five miles away and the major Roman road in the valley below, featured a large sacred precinct enclosed an all four sides by a gallery of colonnades 200 feet long. Within the precinct were two temples, one larger and one smaller, built in typical Romano-Celtic fanum style (ie, a square masonry temple with a central cella inside a square gallery). A cult figure of a deity inhabited the cella. The faithful would offer their prayers and votives in the gallery. The large temple was dedicated to the sanctuary’s primary deity (or deities); the smaller to deities of secondary importance. Welcoming pilgrims to the sanctuary was a forecourt with a well and two small chapel-like structures.

The hilltop sanctuary, visible from Condate (modern-day Rennes) just five miles away and the major Roman road in the valley below, featured a large sacred precinct enclosed an all four sides by a gallery of colonnades 200 feet long. Within the precinct were two temples, one larger and one smaller, built in typical Romano-Celtic fanum style (ie, a square masonry temple with a central cella inside a square gallery). A cult figure of a deity inhabited the cella. The faithful would offer their prayers and votives in the gallery. The large temple was dedicated to the sanctuary’s primary deity (or deities); the smaller to deities of secondary importance. Welcoming pilgrims to the sanctuary was a forecourt with a well and two small chapel-like structures.

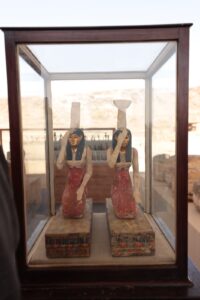

A bronze figurine of the god Mars unearthed at the site suggests that he was one of the deities worshipped in the sanctuary. In Gaul, the local iteration of Mars was not the bloodthirsty god of war so much as a protective healing deity. This was a votive offering left at the sanctuary.

A bronze figurine of the god Mars unearthed at the site suggests that he was one of the deities worshipped in the sanctuary. In Gaul, the local iteration of Mars was not the bloodthirsty god of war so much as a protective healing deity. This was a votive offering left at the sanctuary.

The bronze cup was a votive offering as well, and a luxurious one at that. The cup was found upside down and intact with its two ornately decorated handles still attached. One side of the handle is carved with the relief of a face of a Cupid. Two wings are engraved on each side of the faces. The other end of the handle mounts are

The bronze cup was a votive offering as well, and a luxurious one at that. The cup was found upside down and intact with its two ornately decorated handles still attached. One side of the handle is carved with the relief of a face of a Cupid. Two wings are engraved on each side of the faces. The other end of the handle mounts are

decorated with reliefs of eagles in profile. The curved part of the handle between the terminals feature stylized thunderbolts. These are attributes of the god Jupiter. Such a rich offering suggests Jupiter may also have been worshipped at the sanctuary.

decorated with reliefs of eagles in profile. The curved part of the handle between the terminals feature stylized thunderbolts. These are attributes of the god Jupiter. Such a rich offering suggests Jupiter may also have been worshipped at the sanctuary.

Just outside the temple precinct archaeologists discovered the remains of a public bath building. Most of it is gone, its construction materials taken and reused many centuries ago, but some architectural features have been found, including the tell-tale remains of a hypocaust underfloor heating system and bathing basins. The baths were fed with water from a well dug a few feet away.

Just outside the temple precinct archaeologists discovered the remains of a public bath building. Most of it is gone, its construction materials taken and reused many centuries ago, but some architectural features have been found, including the tell-tale remains of a hypocaust underfloor heating system and bathing basins. The baths were fed with water from a well dug a few feet away.

The excavation site will be opened to the public for the European Archaeology Days, June 17-19. INRAP archaeologists will give visitors the rundown on the ancient sanctuary and the results of the excavation thus far.