A study of the remains of Anne d’Alègre, Countess of Laval (ca. 1565-1619), has found that her teeth were kept in her head by gold wire.

A study of the remains of Anne d’Alègre, Countess of Laval (ca. 1565-1619), has found that her teeth were kept in her head by gold wire.

Anne de Laval’s gold-rigged teeth (and the rest of her remains) were discovered in 1987 during an archaeological excavation of the basement of the chapel in the Vieux-Château de Laval. She was buried in an anthropoid lead coffin that was inside a wooden sarcophagus. A heart-shaped lead casket known as a cardiotaph was placed on the exterior coffin above her chest. Neither the coffin nor the urn had any inscription that might identify the owner.

The lead coffin was opened in a local funeral home, revealing a complete skeleton wrapped in a canvas shroud kept in place by hemp cords. The body had been expertly embalmed and was in good condition. There was enough archaeological and osteological evidence to identify the body as that of Anne d’Alègre. A study found her organs — brain, lungs, digestive tract — had been removed and replaced with aromatic herbs and berries. The cardiotaph contained a desiccated organic amalgam that was almost certainly a human heart with embalming materials.

In 2007, three more sets of bones were rediscovered in the château storerooms. One of them belonged to Anne’s son, Guy, Count of Laval (1585-1605), 20th and last of his name. He had died on the battlefield at just 20 years old. With him died the line and title of the Laval counts.

In 2007, three more sets of bones were rediscovered in the château storerooms. One of them belonged to Anne’s son, Guy, Count of Laval (1585-1605), 20th and last of his name. He had died on the battlefield at just 20 years old. With him died the line and title of the Laval counts.

(And now the moment you’ve been waiting for: an extended, meandering, long-winded digression into the wars of religion that blighted France in the 16th century and ultimately took out the Laval family.

So Martin Luther nails his 95 theses to the door of the Wittenberg Church on Halloween of 1517 and by 1521 the Reformation is making converts in France. Tensions rise and by the 1530s, the French crown is actively persecuting Protestants, from draconian anti-Protestant laws to massacres of thousands. In 1562, 50 Huguenot worshippers, five of them women, one a child, were slaughtered in their meeting house in Vassy by the troops of the Catholic Francis, Duke of Guise. This act is considered the starting point of the French Wars of Religion.

They continued at a staccato pace more than 30 years, stopping and starting as one aristocratic faction vied with another. Protestant Henry of Navarre ultimately asserted his legitimate claim to the throne of France, but he had to fight Catholic opponents to secure it. He finally quelled the objections of holdout areas by converting to Catholicism in 1593. The French Wars of Religion ended officially when King Henry IV issued the Edict of Nantes mandating freedom of religion in 1598.

Anne was born around 1565, the daughter of the Marquis d’Alègre. Her father had taken an opportunistic stance as the religious conflicts escalated. He was Protestant initially, but flipped to the Catholic faction in 1563, a year after Vassy. In 1575 he went back to Protestantism and then retired to live in Rome, ironically, where he died in 1580.

Anne was born around 1565, the daughter of the Marquis d’Alègre. Her father had taken an opportunistic stance as the religious conflicts escalated. He was Protestant initially, but flipped to the Catholic faction in 1563, a year after Vassy. In 1575 he went back to Protestantism and then retired to live in Rome, ironically, where he died in 1580.

His daughter Anne was married to Guy XIX, Count of Laval, in 1583. Guy had been raised Protestant. His father was not just a devout believer, but the founder the first Calvinist church in Brittany. The House of Laval held rich fiefdoms in Brittany, Normandy and Maine and the family’s power and income were little harmed in the first three wars of religion. The Laval holdings were spared destruction in battle and they were not targeted by the extraordinary taxes levied to fund the war.

When the leader of the Protestant forces, the Prince of Condé, died in 1569, an uncle of Guy XIX, Admiral Gaspard de Coligny, was appointed to lead the Huguenot forces. In the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre of 1572, Gaspard was targeted for elimination by the Catholic faction and pulled from his bed and murdered.

Guy XIX fled France, traveling through Protestant-friendly countries from Switzerland to England. He returned to France in 1575 and settled in his chateau at Vitré where Protestantism had more popular support than at Laval. It was during a gap in active war that he married Anne. Two years later, their son, the future Guy XX was born.

Their marriage could not outlast the virulence of this conflict. Guy XIX was killed near the Huguenot-held fortress of La Rochelle in 1586. Baby Guy XX was just a year old at the time, so his mother wielded his power as his guardian and the Dowager Countess of Laval. France was now mired in the 8th War of Religion, and wee Guy was literally smuggled to the safety of the Protestant stronghold of Sedan by his grandmother who dressed as a peasant woman and carried him in her arms 61 miles from Reims.

The King himself tried to run custodial inference. The Lavals were one of the most powerful families in France, and Henry III wanted the baby to be brought back into the Catholic fold. He revoked Anne’s guardianship and appointed two Catholics his guardians instead. He confiscated all the property Guy XIX had left to his son. Henry III’s death did nothing to improve Anne and Guy XX’s circumstances. The ultra-Catholic governor of Brittany confiscated Laval lands and dedicated all of their revenues to the Catholic League. By 1590 Anne wrote to her cousin that their sources of revenue had been so effectively choked off that she and Guy scrambled to get enough to eat. Only with the Edict of Nantes did Anne get her son’s birthright back in 1599. She also remarried, 13 years after the death of her first husband, to the powerful Guillaume IV d’Hauteme, Marshall of France.

The King himself tried to run custodial inference. The Lavals were one of the most powerful families in France, and Henry III wanted the baby to be brought back into the Catholic fold. He revoked Anne’s guardianship and appointed two Catholics his guardians instead. He confiscated all the property Guy XIX had left to his son. Henry III’s death did nothing to improve Anne and Guy XX’s circumstances. The ultra-Catholic governor of Brittany confiscated Laval lands and dedicated all of their revenues to the Catholic League. By 1590 Anne wrote to her cousin that their sources of revenue had been so effectively choked off that she and Guy scrambled to get enough to eat. Only with the Edict of Nantes did Anne get her son’s birthright back in 1599. She also remarried, 13 years after the death of her first husband, to the powerful Guillaume IV d’Hauteme, Marshall of France.

Guy traveled to Italy in 1604 and witnessed the miracle of the blood of San Gennaro in Naples then met with Pope Clement VIII. He declared to the Pope that he would abjure Protestantism and when he returned to France in 1605, that’s what he did, much to his mother’s horror. A few months later, he was dead, killed fighting in Hungary with the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolph II against Sultan Achmet I. His body and heart were returned to Laval for burial and they too wound up in the cross-hairs of religious conflict. It took another three years to settle the bickering over where his heart and body should be interred and for the funeral to finally take place. His mother did not attend the funeral ceremony, nor did any other Protestant.

As Guy XX had no children, no brothers, no relatives at all in line to inherit this important title and property, he should have made explicit arrangements before going off on a perilous journey to fight the Ottomans. He did not, so on his death his seigneuries were inherited by the La Trémoille family and the Laval dynasty ended.

Anne was still going strong, though. The Maréchal de Fervaque died in 1613 and Anne immediately started looking for husband number three. There were a number of suitors — the Prince of Joinville, the Duke of Chevreuse — as her fortune and social status made her a desirable partner. Her romantic life was the talk of Paris as was her daring fashion and carriage racing hobby. She never did get around to that third marriage. She died in 1619 after many months of illness. The canons of the Church of Saint-Tugal would not allow her to be buried with her husband, her son’s heart and all the past counts and countesses of Laval because she was Protestant. She was buried in the chapel of the Chateau de Laval instead.

Guy XX’s remains were exhumed when the church was demolished to make way for a new government building during the French Revolution. They were moved to the museum stores in the Vieux-Château de Laval, dodging the fate of so many scattered bones of French nobles.)

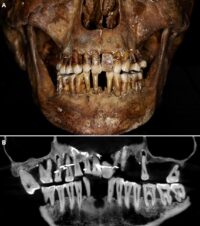

The new study  focused on Anne’s teeth using the digital technology used in dental practices today to learn more about a rare and expensive practice of historic dentistry only available to the elite. Scans and imaging found she suffered from severe periodontal disease leaving her teeth rattling loose in her jaw. To keep them in place, the upper left jaws were tied with gold wire .4 mm thick. The upper incisor was replaced by a prosthesis that was tied in place by a gold wire .2 mm thick. The wear on the prosthesis indicates it was used for many years.

focused on Anne’s teeth using the digital technology used in dental practices today to learn more about a rare and expensive practice of historic dentistry only available to the elite. Scans and imaging found she suffered from severe periodontal disease leaving her teeth rattling loose in her jaw. To keep them in place, the upper left jaws were tied with gold wire .4 mm thick. The upper incisor was replaced by a prosthesis that was tied in place by a gold wire .2 mm thick. The wear on the prosthesis indicates it was used for many years.

A “Cone Beam” scan, which uses X-rays to build three-dimensional images, showed that gold wire had been used to hold together and tighten several of her teeth.

She also had an artificial tooth made of ivory from an elephant—not hippopotamus, which was popular at the time.

But this ornate dental work only “made the situation worse”, said Rozenn Colleter, an archaeologist at the French National Institute for Preventive Archaeological Research and lead author of the study.

The gold wires would have needed repeated tightening over the years, further destabilizing the neighboring teeth, the researchers said.

Long-term dental health was probably not her goal. She was willing to suffer all that pain and tightening so she didn’t look toothless. That third husband was still on the table, after all, and disfigurement of any kind in that era was deemed a reflection of moral failure. For Anne appearances mattered enough to endure the agony.

The cross is a foot long from top to bottom and is adorned with more crosses. There are Canterbury crosses 4 cm (1.6 inches) wide at the end of the cross-arms arm and the bottom of the descending arm. At the center point of the crossarm is an equal-armed cross 8 cm (3.15 inches) wide. Between each of the arms of the central cross are oval human faces cast in silver with blue glass eyes.

The cross is a foot long from top to bottom and is adorned with more crosses. There are Canterbury crosses 4 cm (1.6 inches) wide at the end of the cross-arms arm and the bottom of the descending arm. At the center point of the crossarm is an equal-armed cross 8 cm (3.15 inches) wide. Between each of the arms of the central cross are oval human faces cast in silver with blue glass eyes. The burial dates to between 630 and 670 A.D. At that time, Harpole was part of the Kingdom of Mercia which was smack in the middle of converting to Christianity. The first introduction of Christianity to Mercia came in 628 when the pagan King Penda conquered Christian Saxon-held territories. Penda’s son Peada sealed the deal in 655 when he converted to Christianity and agreed to evangelize and convert his subjects as a condition of his marriage to Alchflaed, the daughter of King Oswiu of Northumbria.

The burial dates to between 630 and 670 A.D. At that time, Harpole was part of the Kingdom of Mercia which was smack in the middle of converting to Christianity. The first introduction of Christianity to Mercia came in 628 when the pagan King Penda conquered Christian Saxon-held territories. Penda’s son Peada sealed the deal in 655 when he converted to Christianity and agreed to evangelize and convert his subjects as a condition of his marriage to Alchflaed, the daughter of King Oswiu of Northumbria.