A preventative archaeology excavation at a real estate development site in the historic center of Narbonne, southern France, has uncovered the remains of an early imperial-era Roman wall and tower. Preliminary estimates based on the measurements and construction style of the wall and tower date them to the last decades of the 1st century B.C. The discovery came as a surprise as this is the first evidence that the ancient city of Narbo Martius, the first Roman colony established outside of Italy, had defensive walls of any kind.

A preventative archaeology excavation at a real estate development site in the historic center of Narbonne, southern France, has uncovered the remains of an early imperial-era Roman wall and tower. Preliminary estimates based on the measurements and construction style of the wall and tower date them to the last decades of the 1st century B.C. The discovery came as a surprise as this is the first evidence that the ancient city of Narbo Martius, the first Roman colony established outside of Italy, had defensive walls of any kind.

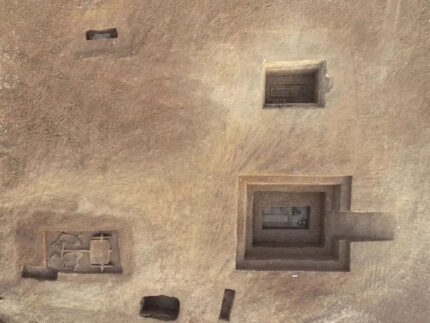

The excavation unearthed a section of wall 100 feet long. It is an enclosing wall connected to a round masonry tower. The tower was constructed in an unusual fashion: the base of the round tower is inset in a square foundation. This was likely done to give the massive walls additional stability.

The excavation unearthed a section of wall 100 feet long. It is an enclosing wall connected to a round masonry tower. The tower was constructed in an unusual fashion: the base of the round tower is inset in a square foundation. This was likely done to give the massive walls additional stability.

Colonia Narbo Martius was founded by Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus in 118 B.C., two years after he and Quintus Fabius Maximus Allobrogicus defeated the Arverni and the Allobroges and conquered all of southern Gaul. As proconsul of Gaul, Gnaeus Domitius built the first Roman road in Gaul, the Via Domitia, running from Spain to Italy through his new colony. He then built the second Roman road in Gaul, the Via Aquitania, that ran from Narbo through the Aquitaine province to the Atlantic Ocean. The city was also located at the mouth of the Aude river at that time, situating it at a strategic crossroads for trade, agriculture, travel and Roman military expansion.

Colonia Narbo Martius was founded by Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus in 118 B.C., two years after he and Quintus Fabius Maximus Allobrogicus defeated the Arverni and the Allobroges and conquered all of southern Gaul. As proconsul of Gaul, Gnaeus Domitius built the first Roman road in Gaul, the Via Domitia, running from Spain to Italy through his new colony. He then built the second Roman road in Gaul, the Via Aquitania, that ran from Narbo through the Aquitaine province to the Atlantic Ocean. The city was also located at the mouth of the Aude river at that time, situating it at a strategic crossroads for trade, agriculture, travel and Roman military expansion.

Marcus Tullius Cicero, in his oration in defense of Marcus Fonteius, the former praetor of Gallia Narbonensis who was accused by Gallic tribespeople of financially exploiting the province for his own gain, describes Narbo Martius as “a citizen-colony, which stands as a watch-tower and bulwark of the Roman people, and a barrier of defense against these tribes.” Cicero made that speech in 69 B.C., and after that Narbo’s importance only grew. Julius Caesar refounded it in 46-45 B.C. as a colony for the veterans of his Tenth Legion, then Augustus made it the capital of the province of Gallia Narbonensis in 22 B.C.

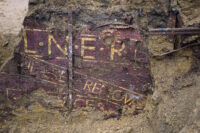

The area of Narbonne currently under excavation was on the outskirts of the ancient city. It was built around 50 A.D. to store trade goods. The excavation revealed three or four warehouses on the site, three streets, an alley and a system of intersecting canals that managed rain and waste water evacuation. One of the warehouses had an unusual design: the ground floor, used for storage, was kept clean by a drainage crawl space made out of recycled amphorae. The upper floor was a either a home or office, and a rather nice one at that, with concrete floors, mosaics and mud brick walls painted to look like marble panels. This warehouse and another one were severely damaged in the same fire event, but were reconstructed.

The area of Narbonne currently under excavation was on the outskirts of the ancient city. It was built around 50 A.D. to store trade goods. The excavation revealed three or four warehouses on the site, three streets, an alley and a system of intersecting canals that managed rain and waste water evacuation. One of the warehouses had an unusual design: the ground floor, used for storage, was kept clean by a drainage crawl space made out of recycled amphorae. The upper floor was a either a home or office, and a rather nice one at that, with concrete floors, mosaics and mud brick walls painted to look like marble panels. This warehouse and another one were severely damaged in the same fire event, but were reconstructed.

These discoveries are linked to the urban port of Narbo Martius , located along the ancient arm of the Aude. This constitutes, with the maritime outer port whose remains have been observed at several points (Île Saint-Martin in Gruissan, Mandirac, La Nautique), a complex port system whose importance is attested in particular in the texts and ancient inscriptions. This excavation contributes to the identification of the ancient route of the river, the course of which was partly artificialized during the canalization of the Robine in the 18th century .

The structures, which would usually be reburied or, quel dommage, allowed to be destroyed when construction at the site resumed, are so significant that the developers have decided to integrate the finds into their new construction.